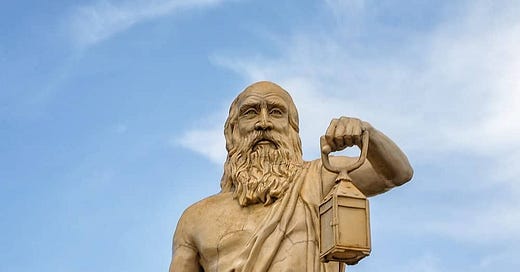

This is a light and whimsical post about one of ancient Greece’s most interesting characters, Diogenes of Sinope (412/404 BC – 323 BC), who listened to his inner voice despite hardship and public pressure. His decision to live ascetically and shamelessly free from social constraints continues to have lasting appeal.

An aphorism is a concise, terse, or laconic expression of a general truth or principle.

Diogenes of Sinope was one of the founders of Cynicism, a school of ancient Greek philosophy, and his life, ideas and expressions continue to have lasting appeal.

He is most famous for his encounter with Alexander the Great when Alexander visited Corinth in 336 BC. According to Plutarch, the story is as follows:

Now a great assembly of the Greeks was held at the Isthmus, where a vote was passed to make an expedition against Persia with Alexander, and he was proclaimed their leader. Thereupon many statesmen and philosophers came to him with their congratulations, and he expected that Diogenes of Sinope also, who was tallying in Corinth, would do likewise. But since that philosopher took not the slightest notice of Alexander, and continued to enjoy his leisure in the suburb Craneion, Alexander went in person to see him; and he found him lying in the sun. Diogenes raised himself up a little when he saw so many persons coming toward him, and fixed his eyes upon Alexander. And when that monarch addressed him with greetings, and asked if he wanted anything, “yes,” said Diogenes, “stand a little out of my sun.” It is said that Alexander was so struck by this, and admired so much the haughtiness and grandeur of the man who had nothing but scorn for him, that he said to his followers, who were laughing and jesting about the philosopher as they went away, “But verily, if I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.”

What a story! Here you have a man who had no possessions at all, living on the streets as a dog and begging for his food as a homeless man, and the most glorious man alive, whose name and actions would echo for eternity, comes to him and asks him what he wants, and he says - get out of my way! What power of thinking, of composure, of self-assuredness, to have nothing, to need nothing, to retain your wits regardless of the vicissitudes of fate. It reminds me of Rudyard Kipling’s wonderful poem “If”: “…If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch, If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you, If all men count with you, but none too much; If you can fill the unforgiving minute With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run, Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!”

Per Ecclesiastes 3:20, “All go to one place; all were formed of the dust, and all will return to dust.” All of the world’s honors, riches, glory ultimately mean nothing as we all return to the same source; the adventures we go on, the conflicts and struggles we endure are mere trifles in the grand scheme of things, and it takes a man of wisdom like Diogenes to think for himself and not give credence to such silly things.

The book “Diogenes of Sinope - Life and Legend” contains every extant reference to the man. These references are from the following authors: Aelian, Aesop, Aulus Gellius, Apuleius, Athenaeus, Augustine, Basil of Caesarea, Clement, Cicero, Dio Chrysostom, Diogenes Laertius, Epictetus, Greek Anthology, Julian, Lucian, Marcus Aurelius, Origen, Philostratus, Plutarch, Seneca, Socrates Scholasticus, Strabo, Tertullian. The book was interesting to read; some writers resonated more than others. For example Dio Chrysostom was longwinded and boring despite having the most coverage.

Here’s a brief background of Diogenes before letting some of the best aphorisms speak for themselves. He was the son of the mintmaster of Sinope. He started working in the mint but was caught debasing the currency and so he fled into exile. While fleeing, the boat he was on was captured by pirates and he was sold as a slave. He eventually secured his freedom and became more or less a homeless bum (or “dog”) which was a philosophical choice, and he insulted or praised those who passed by him as he begged for basic sustenance without regarding for wealth or privilege.

He was a fairly prolific author and also wrote tragedies, none of which survive. He was a contemporary both of Plato and of Alexander the Great. He lived to an old age and developed a large following as one of the founders of Cynicism. The Stoics, Cynics, Epicureans, and Skeptics practiced a philosophy focusing on an individual’s approach to life rather than on the structure of the state, philosophies which become more relevant as we enter a time with major reductions in material consumption.

To be clear, I am not endorsing Diogenes’s actions or ascetic-like philosophy except to the extent they shine a light on the absurdity of mankind. It is the mark of wisdom that one can understand and appreciate a style of thinking without accepting or rejecting it; to hold in one’s mind competing ideas and ideals gives rise to the complexification process at the heart of life.

The below are the aphorisms and anecdotes that stood out to me. They are organized alphabetically by author, not chronologically.

Aelian, Varia Historia III.29:

Diogenes the Sinopian used to say of himself that he fulfilled and suffered the imprecations in the Tragedy, being a Vagabond, destitute of a house, deprived of his country, a Begger, ill clothed, having his livelihood only from day to day: And yet he was more pleased with this condition, then Alexander with the command of the whole World, when having conquered the Indians he returned to Babylon.

Aelian, Varia Historia X.11:

Diogenes had a pain in his shoulder by some hurt, as I conceive, or from some other cause: and seeming to be much troubled, one that was present being vexed at him, derided him, saying, “Why then do you not die, Diogenes, and free yourself from ills? He answered, “It was fit that those persons who knew what was to be done and said in life (of which he professed himself one) should live. Wherefore for you (he said) who know neither what is fit to be said or done, it is convenient to die; but me, who know these things, it behoveth to live.”

Aelian, Varia Historia XIV:

It is reported that Plato used to say of Diogenes, “This man is Socrates mad.”

Aesop:

A bald man insulted Diogenes the Cynic and Diogenes replied, “Far be it from me to make insults! But I do want to compliment your hair for having abandoned such a worthless head.”

Diogenes Laertius, Book 6:

Menippus in his “Sale of Diogenes” tells how, when he was captured [by the pirates] and put up for sale, he was asked what he could do. He replied, “Govern men.” And he told the crier to give notice in case anybody wanted to purchase a master for himself. Having been forbidden to sit down, “It makes no difference,” said he, “for in whatever position fishes lie, they still find purchasers.” And he said he marveled that before we buy a jar or dish we try whether it rings true, but if it is a man are content merely to look at him. To Xeniades who purchased him he said, “You must obey me, although I am a slave; for, if a physician or a steersman were in slavery, he would be obeyed.” Eubulus in his book entitled The Sale of Diogenes tells us that this was how he trained the sons of Xeniades.

He lit a lamp in broad daylight and said, as he went about, “I am looking for an [honest] man.”

One day he got a thorough drenching where he stood, and, when the bystanders pitied him, Plato said if they really pitied him, they should move away, alluding to his vanity.

When Lysias the druggist asked him if he believed in the gods, “How can I help believing in them,” said he, “when I see a god-forsaken wretch like you?"

Dionythe the Stoic says that after Chaeronea he was seized and dragged off to Philip, and being asked who he was, replied, “A spy upon your insatiable greed.” For this he was admired and set free.

Being short of money, he told his friends that he applied to them not for alms, but for repayment of his dues.

When a youth effeminately attired put a question to him, he declined to answer unless he pulled up his robe and showed whether he was man or woman.

Rhetoricians and all who talked for reputation he used to call “thrice human,” meaning thereby “thrice wretched.” (Make note, Substack authors…)

When someone reproached him with his exile, his reply was, “Nay, it was through that, you miserable fellow, that I came to be a philosopher.” Again, when someone reminded him that the people of Sinope had sentenced him to exile, “And I them,” said he, “to home-staying.”

Being reproached one day for having falsified the currency, he said, “That was the time when I was such as you are now; but such as I am now, you will never be.”

He once begged alms of a statue, and, when asked why he did so, replied, “To get practice in being refused.” In asking alms - as he did at first by reason of his poverty - he used this form: “If you have already given to anyone else, give to me also; if not, begin with me.”

To the question what is wretched in life he replied, “An old man destitute.”

Being asked what creature’s bite is the worst, he said, “Of those that are wild a sycophant’s; of those that are tame a flatterer’s.”

Being asked whether he had maid or boy to wait on him, he said “No.” “If you should die, then, who will cary you out to burial?” “Whoever wants the house,” he replied.

Being asked what was the right time to marry, Diogenes replied, “For a young man not yet: for an old man never at all.”

To the question what wine he found pleasant to drink, he replied, “That for which other people pay.”

When he was advised to go in pursuit of his runaway slave, he replied, “It would be absurd, if Manes can live without Diogenes, but Diogenes cannot get on without Manes.”

Some authors affirm that the following also belongs to him: that Plato saw him washing lettuces, came up to him and quietly said to him, “had you paid court to Dionysius, you wouldn’t now be washing lettuces,” and that he with equal calmness made answer, “If you had washed lettuces, you wouldn’t have paid court to Dionysius.”

When someone said, “Most people laugh at you,” his reply was, “And so very likely do the asses at them; but as they don’t care for the asses, so neither do I care for them.”

Alexander once came and stood opposite him and said, “I am Alexander the great king.” “And I,” said he, “am Diogenes the Cynic.” Being asked what he had done to be called a hound, he said, “I fawn on those who give me anything, I yelp at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals.”

On being asked what he had gained from philosophy, he replied, “This at least, if nothing else - to be prepared for every fortune.”

To the man who said to him, “you don’t know anything, although you are a philosopher,” he replied, “Even if I am but a pretender to wisdom that in itself is philosophy.”

When someone brought a child to him [for tutoring] and declared him to be highly gifted and of excellent character, “What need then,” said he, “has he of me?”

Seeing a young man behaving effeminately, “Are you not ashamed,” he said, “that your own intention about yourself should be worse than nature’s: for nature made you a man, but you are forcing yourself to play the woman.”

To one who protested that he was ill adapted for the study of philosophy, he said, “Why then do you live, if you do not care to live well?”

Being asked what was the most beautiful thing in the world, he replied, “Freedom of speech.”

He would ridicule good birth and fame and all such distinctions, calling them showy ornaments of vice.

Diogenes is said to have been nearly ninety years old when he died. Regarding his death there are several different accounts. One is that he was seized with colic after eating an octopus raw and so met his end. Another is that he died voluntarily by holding his breath….Over his grave they set up a pillar and a dog in Parian marble upon it. Subsequently his fellow-citizens honoured him with bronze statues, on which these verses were inscribed: Time makes even bronze grow old, but they glory, Diogenes, all eternity will never destroy. Since thou alone didst point out to mortals the lesson of self-sufficingness and the easiest path of life.” But some say that when dying he left instructions that they should throw him out unburied, that every wild beast might feed on him, or thrust him into a ditch and sprinkle a little dust over him.

[Cynics] also hold that we should live frugally, eating food for nourishment only and wearing a single garment. Wealth and fame and high birth they despise. Some at all events are vegetarians and drink cold water only and are content with any kind of shelter or tubs, like Diogenes, who used to say that it was the privilege of the gods to need nothing and of god-like men to want but little.

Epictetus, Discourses 4.1:

Diogenes was free. How came he by this? Not because he was of free parents (he was not), but because he was free himself, had cast away all the weakness that might give slavery a hold on him, and so no one could approach or lay hold on him to enslave him. Everything he had he was ready to let go, it was loosely attached to him. If you had laid hold on his property, he would have let it go rather than have followed you for it; if you seized his leg, he would have let that go; if his whole poor body, he would have let his whole body go; and the same with kinsfolk, friends, and country. For he knew whence he had them and from whom, and on what conditions he received them. His true ancestors, the gods, and his his true Country he would never have deserted, nor have suffered another to yield them more obedience or attention, nor would another have died for his Country more cheerfully. For he never sought to get the reputation of acting for the universe, but he remembered that everything that comes to pass has its source there and is done for that true Country’s sake and is entrusted to us by Him that governs it. Wherefore look what he says and writes himself: ‘Therefore, Diogenes,’ he says, ‘you have power to converse as you will with the king of the Persians and with Archidamus, king of the Lacedaemonians.’ Was it because he was the son of free parents? When all the men of Athens and Lacedaemon and Corinth were unable to converse with them as they wished, and feared and flattered them instead, was it because they were the sons of slaves? ’Why have I the power to do it then?’ he says. ‘Because I count my poor body not my own because I need nothing, because law and nothing else is all in all to me.’ These were the things which left him free.

Greek anthology anonymous

Diogenes the Cynic, on his arrival in Hades, after his wise old age was finished, laughed when he saw [king] Croesus. Spreading his cloak on the ground near the king, who once drew great store of gold from the river, he said: “Now, too, I take up more room than you; for all I had I have brought with me, but you, Croesus, have nothing.”

Julian, Oration 6

Then let him who wishes to be a Cynic, earnest and sincere, first take himself in hand like Diogenes and Crates, and expel from his own soul and from every part of it all passions and desires, and entrust all his affairs to reason and intelligence and steer his course by them. For this in my opinion was the sum and substance of the philosophy of Diogenes.

Lucian, The Way to Write History 3

Such sights and sounds, my Philo, brought into my head that old anecdote about the Sinopian. A report that Philip was marching on the town had thrown all Corinth into a bustle; one was furbishing his arms, another wheeling stones, a third patching the wall, a fourth strengthening a battlement, every one making himself useful somehow or other. Diogenes having nothing to do - of course no one thought of giving him a job - was moved by the sight to gird up his philosopher’s cloak and began rolling his tub-dwelling energetically up and down the Craneum; an acquaintance asked, and got, the explanation: “I do not want to be thought the only idler in such a busy multitude; I am rolling my tub to be like the rest.”

Plutarch, How a man may receive advantage and profit from his enemies

There are others who, as Diogenes and Crates did, have made banishment from their native country and loss of all their goods a means to pass out of a troublesome world into the quiet and serene state of philosophy and mental contemplation.

And here may be inserted that wise and facetious answer of Diogenes to one that asked him how he might be revenged of his enemy: The only way, says he, to gall and fret him effectually is for yourself to appear a good and honest man. The common people are generally envious and vexed in their minds, as oft as they see the cattle of those they have no kindness for, their dogs, or their horses, in a thriving condition; they sigh, fret, set their teeth, and show all the tokens of a malicious temper, when they behold their fields well tilled, or their gardens adorned and beset with flowers. If these things make them so restless and uneasy, what dost thou think they would do, what a torment would it be to them, if thou shouldst demonstrate thyself in the face of the world to be in all thy carriage a man of impartial justice, a sound understanding, unblamable integrity, of a ready and eloquent speech, sincere and upright in all your dealings, sober and temperate in all that you eat or drink.

Hopefully you found some of these anecdotes and aphorisms about this silly, sarcastic homeless fellow, living in a completely different age with quite different societal values, whose name and deeds we know about 2,300 years later as interesting as I did.

Thanks for reading.

He own nothing and was happy

I personally never heard of Diogenes untill now so I appreciate you bringing him to my attention.

In regards to his philosophy I can see great wisdom in it. For if you can let go of all worldly possessions you are not beholden to the tax man or any authority and are free.

My favorite quote which brought smile and laugh to my face , “Far be it from me to make insults! But I do want to compliment your hair for having abandoned such a worthless head.” 😆

Nice article and very interesting.