This is a narrowly-tailored post about how Rome’s destruction of its arch-rival Carthage led to unprecedented material prosperity that undermined the moral foundations of Rome and paved the path to empire. Comparisons to the modern era with the total triumph of Western-style oligarchical managerialism under the propaganda guise of “democracy” are apt.

This is a post on the Roman historian Sallust’s The Jugurthine War, one of his two fully extant works.1 Based on Quintus Curtius’s translation, Jugurtha tells a narrative within Roman history which illustrates the principle that achieving total victory is never what it seems. It’s also a great anti-hero story that could make a great film.

First, about the author. Sallust is the earliest Latin-language Roman historian with surviving works to his name. He served under Julius Caesar, including when he crossed the Rubicon, sharing a meal with him the next night per Plutarch. Sallust had much political and administrative experience along with deeply populist, anti-elitist leanings. He also wrote shortly before the Christian era, around 40 BC, and it is refreshing to see the world before its transvaluation of values under Paul of Tarsus.

Sallust’s writing is sparse and terse, contrasted against his rival Cicero’s long and poetic speeches. Nietzsche credits Sallust in Twilight of the Idols: "My sense of style, for the epigram as a style, was awakened almost instantly when I came into contact with Sallust" and praises him for being "condensed, severe, with as much substance as possible in the background, and with cold but roguish hostility towards all 'beautiful words' and 'beautiful feelings’”. Powerful compliment.

Sallust’s primary focus is on morality: who has or lacks noble virtues, which he believed to be specifically martial virtues. Martial virtues include the willingness to engage in warfare, to fight properly and honorably on behalf on the Roman people, its glory and its ancestors, to pursue right aims and right tactics, and to give one’s life when necessary rather than risk dishonor (as honor and glory were in some sense immortal versus the decaying weakness of the physical form). Stressing marital virtues was especially important for Sallust because he felt that Rome had fallen into decadence, corruption, individualism and greed. To Sallust, martial virtues and chasing wealth were competing priorities; only one could have primacy in both society and as individuals. There is no sense of Nietzsche’s slave morality or the ascetic ideal in his work, although there is a strong sense of Platonism.2

The Jugurthine War highlights the corruption that Rome experienced in the aftermath of its victory over Carthage in the Punic Wars where they wiped their rival off the map. Achieving unconditional victory may have been as much of a curse as a blessing because life is struggle and lacking challenge for survival leads to decadence and decay.3 We are slowly learning this lesson now as globohomo stands alone, victorious, basking in Fukuyama’s “end of history” in full power on the world stage as corruption and softness grows. As Julius Evola wrote in Ride the Tiger:

Hegel rightly wrote that the epochs of material well-being are blank pages in the history book, and Toynbee has shown that the challenge to mankind of environmentally and spiritually harsh and problematic conditions is often the incentive that awakens the creative energies of civilization. In some cases, it is not paradoxical to say that the man of good will should try to make life difficult for his neighbor! It is a commonplace that all the higher virtues attenuate and atrophy under easy conditions, when man is not forced to prove himself in some way; and in the final analysis it does not matter in such situations if a good number fall away and are lost through natural selection. Andre Breton was right when he wrote that “we must prevent the artificial precariousness of social conditions from concealing the real precariousness of the human condition.”

The Jugurthine War features a standout cast of characters: there’s Jugurtha, a kind of antihero/villainous Joker-type mixed with a charismatic Arnold Schwarzenegger; there’s the scandalous corruption of the Roman Senate; there’s Gaius Memmius, the honest elected tribune of the plebs who would hold the Senate to account; there’s the introductions of both Marius and Sulla who would later go on to shake Rome to its foundations. It would make a great movie or limited television series if globohomo wasn’t busy pushing worthless slop onto the masses to rot their brains.

Sallust chose to cover this conflict because “for the first time action took place to oppose the arrogance of the nobility.” Let’s see what he means…

Jugurtha’s background

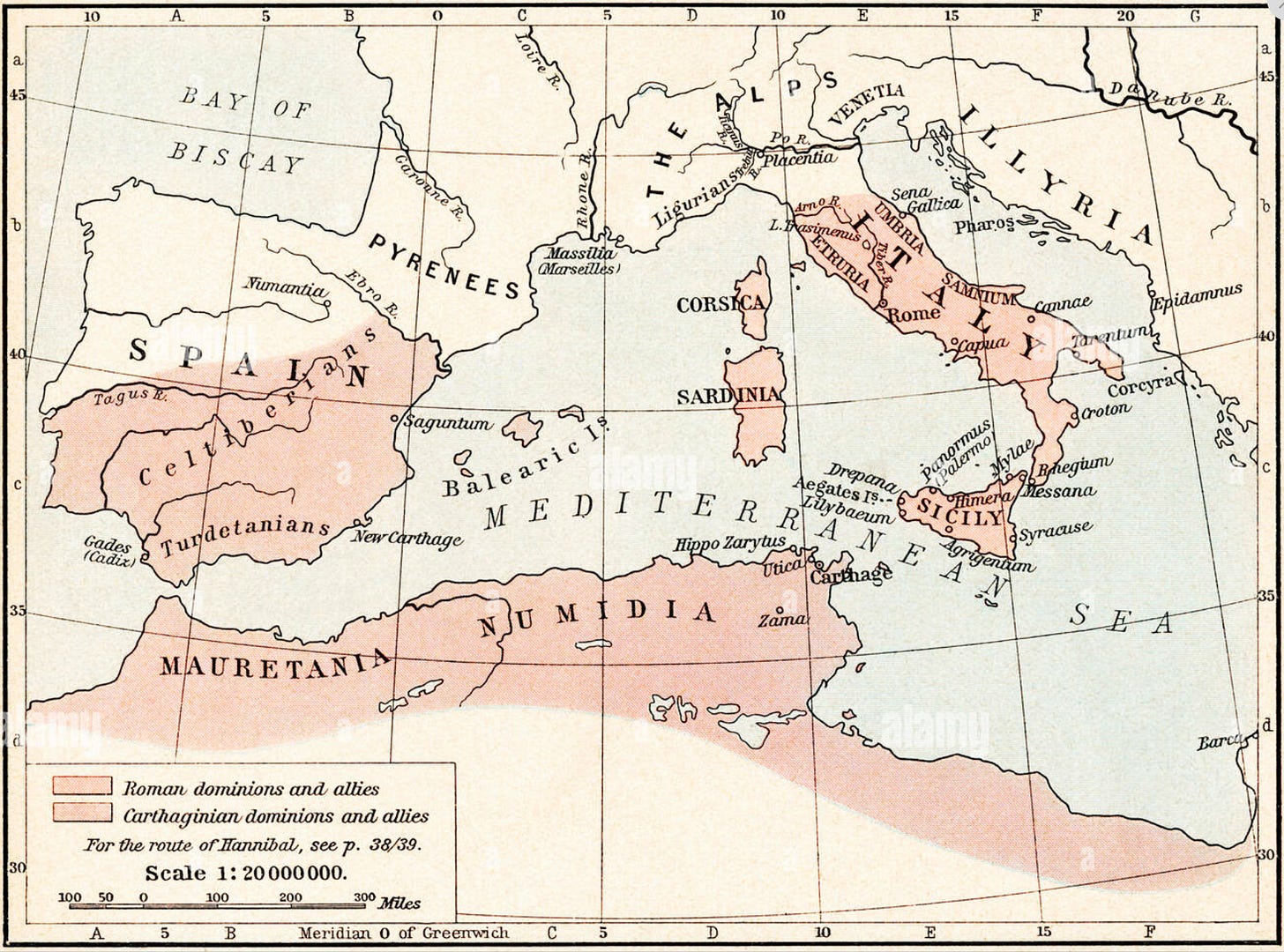

Numidia was a large region in North Africa that bordered the remains of Carthage. The king of Numidia helped the Romans defeat and destroy Carthage, and in return for his loyalty and assistance the territory of Numidia was greatly expanded. When he died his son Micipsa ascended to the throne.

Micipsa brought into the royal household his brother’s bastard child Jugurtha as a favor (which, as we will see, will prove the maxim “no good deed goes unpunished”). However, Jugurtha was the product of a relationship with a concubine so he was not included in the line of succession. Micipsa had two legitimate heirs who were both much younger than Jugurtha.

When Jugurtha came of age he was handsome, charismatic, with a manly disposition. He mastered horsemanship and hunting, practiced with the javelin and competed with his peers in running. He soon became famous and everyone loved him, as he was humble despite his growing accomplishments.4

Micipsa grew worried about Jugurtha’s ambition and popularity, so he shipped him off to assist the Romans during the Numantine War, hoping he would be killed in the fighting. Instead Jugurtha distinguished himself with his courage and sharp and probing mind, he learned the Roman worldview, tactics and strategies, and made allies out of many of them. He also saw how corrupt Rome had become. When he went home with letters from Rome praising him, Micipsa felt compelled to elevate Jugurtha into the royal family and adopt him. He was clear that Jugurtha was to share Numidia with Micipsa’s two sons upon his death. Then he promptly died.

Jugurtha becomes king

Soon after Micipsa died, Jugurtha, who had nurtured a hidden but overweening ambition, arranged an ambush and murdered Micipsa’s younger son. The older son, Adherbal, shocked, raised an army and faced Jugurtha’s forces on the field of battle, but he lost and then fled to Rome. Imagine this: a father magnanimously adopts a bastard child of his brother as his own, then the adopted bastard child kills one of his blood children and seizes the rest of the country from the other child.

Jugurtha’s actions were a scandal in Rome but the Senate thought: why should we get involved in this? It’s not our business. Furthermore Jugurtha, who understood Rome’s ways, bribed as many Senators and powerful individuals as he could get his hands on: “Therefore he sent a few ministers to Rome a few days later with an ample supply of gold and silver; he directed them first to satisfy his old friends with gifts, and then reach out to new people. The goal was to do whatever could be done with lavish giving in the shortest time possible.”

Adherbal pled his case to the Senate, highlighting his family’s loyalty and the treacherous, ungrateful character of his cousin, as well as the cruelty Jugurtha inflicted on Adherbal’s loyalists — “As for those captured by Jugurtha, some have been crucified, others thrown to wild animals; the few allowed to live have been imprisoned in darkness to live out a ‘life’ worse than death amid sorrow and pain.” But his speech was for naught; the faction in the Senate who had received bribery and favors emerged victorious. They ruled that Adherbal and Jugurtha would divide Numidia equally between themselves.

Jugurtha was unhappy with this arrangement, though. He wanted all of Numidia, and he tried but failed to goad Adherbal into war with underhanded, violent provocations. Adherbal was mild in temperament and was afraid of Jugurtha’s power so he did not respond. So Jugurtha shrugged, discarded even a pretext for war and invaded Adherbal’s lands, destroying his forces in battle and chasing him to a fortress hideaway. Adherbal sent word to Rome asking for help again. Rome sent important senior officials to mediate but Jugurtha would not lift the siege. He captured Adherbal and tortured him to death, along with the Roman citizens within the city’s walls who had supported him.

Superficial war with Rome

When word of Jugurtha’s actions reached Rome, the same agents of the king minimized his atrocities. It looked like Jugurtha would get away with his crimes because of the massive bribes handed out except for the actions of Gaius Memmius, the elected tribune of the plebs. Memmius was “a keenly intelligent man opposed to the power of the nobility, [and he] explained to the Roman people that the gridlock was an attempt to whitewash Jugurtha’s crimes by a few of his senatorial collaborators.” As a result Rome reluctantly declared war on Jugurtha, but Jugurtha bribed the consul sent to wage the war, Lucius Calpurnius Bestia, and Calpurnius agreed to extremely light peace terms. The Senate waffled at this scandalous result while the lower classes were outraged; the upper classes were torn between their love of bribes and their fear of the masses.

Gaius Memmius stirred up the passions of the plebs again, referring to the assassination of the populist Gracchus brothers5 (which I may cover in a future post) and demanded that Jugurtha at the very least come to Rome to answer to the Senate for his crimes. Jugurtha reluctantly agreed, but when he came he bribed the tribune of the plebs Caius Baebius, who protected the king by telling him not to speak to the tribunal. So the plebs left the tribunal having been played for fools.

Despite Jugurtha’s apparent victory, he miscalculated and overreached by ordering the murder of a potential rival in Rome. While the murder was successful, the assassin was caught. Jugurtha was then expelled from Italy by an outraged Senate, and he is supposed to have said while leaving, “If the right buyer comes along, this city is a corrupt one, and one that will soon be destroyed.”

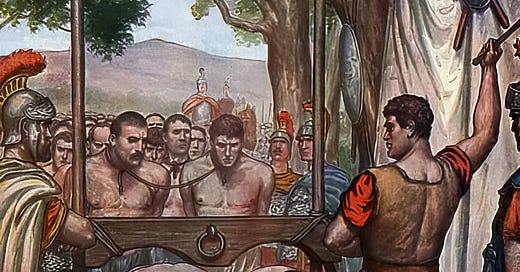

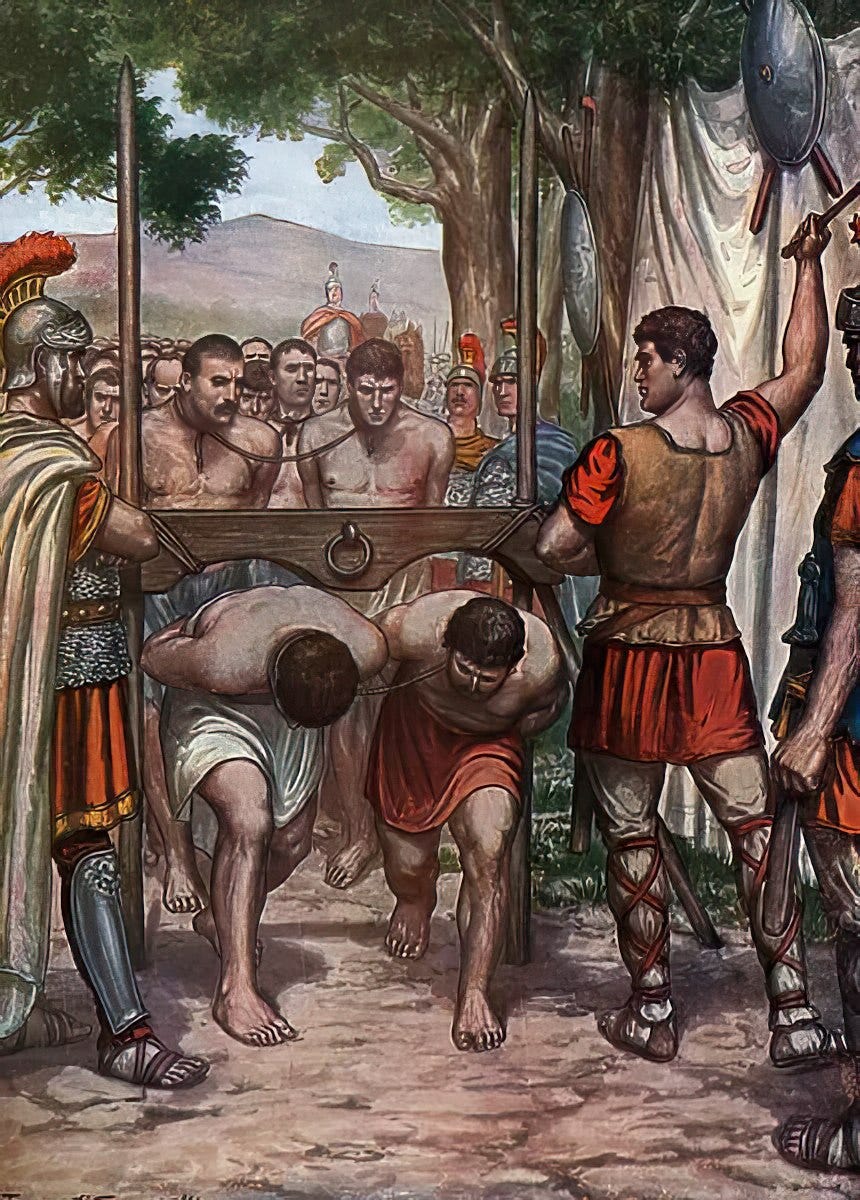

The war resumed between Numidia and Rome. Through guile and corruption Jugurtha surrounded Rome’s unmotivated army and forced its soldiers to pass, humiliated, under the yoke in a surrender ritual.

The Roman people were again outraged at this result, and they forced a measure (against strong Senate opposition) against those who had taken bribes from Jugurtha. The plebs and the Patricians were set against each other. According to Sallust, this sorry state of affairs was due to the lack of external threats after the defeat of Carthage:

The habits of partisanship, factionalism, and all related pernicious practices had arisen in Rome a few years before due to excessive leisure and the abundance of all things that mortal men consider most important. Before Carthage was destroyed the senate and the Roman people handled the political affairs of the republic peacefully and with discipline; rivalries among citizens for glory or domination did not exist. Fear of the external enemy kept the state focused on useful domestic endeavors. But when this fear lost its hold on the minds of the citizenry, unrestraint and arrogance inevitably grew, as these vices go hand-in-hand with opulence. Thus the leisure they hoped for during their hardships was - after they had gotten it - more bitter and unkind than their original troubles. So the nobles abused their positions to indulge their vices, and the people abused their liberty to indulge their own; every man stole, plundered, and robbed for himself. Thus everything was pulled forcibly to two extremes; and the republic, which was caught in the middle, was torn apart.

Does that not sound like the state of affairs today?

After suffering the latest humiliation, Rome finally had enough. The consul Metellus prepared to take the Jugurthine war seriously and with an eye for achieving victory.

Real war with Rome

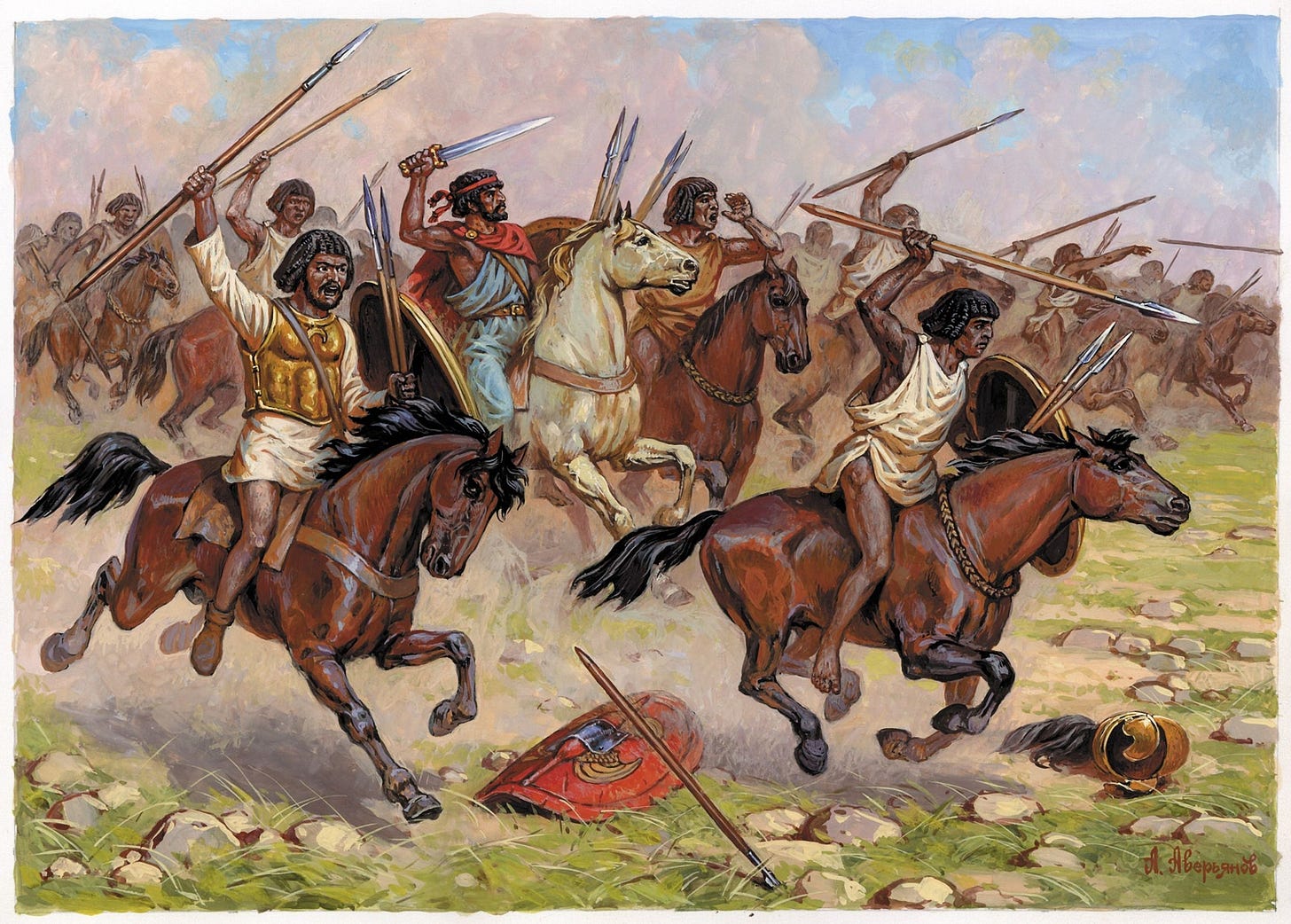

Knowing the strength of Rome, Jugurtha knew that he would not be able to defeat them head-on — at least not at first. He adapted classical insurgency/guerilla tactics, employing flexible hit and run strategies, promising alternatively to surrender and then reneging and refusing to engage in outright combat. Over time this would drain and confuse Roman forces who were fighting in a hostile territory with unknown terrain. In response Metellus adapted counter-insurgency tactics; taking and razing key fortresses and food supplies, turning Jugurtha’s allies with promises and pressure, and killing the adult male population of any towns seen as excessively loyal to Jugurtha. “These tactics frightened the king much more than the previous battle that had gone badly for him. For while he had placed all his hopes in making use of hit-and-run tactics, he was forced to follow around his opponent; when he was deprived of the ability to conduct defensive operations in his own areas, he had to carry on the fight in other places.”6

These tactics over time worked and had a cumulative effect. Meanwhile Metellus’s second in command, Marius, decided to seek the consulship, which he won with the support an enthusiastic pleb class and then usurped Metellus’s command in Numidia even as he was closing in on victory.7 Marius’s own second in command Sulla would later engage in a bitter civil war against Marius himself.8 Even when an ambitious military commander sought glory and martial virtues over money, it seems it was difficult to separate such ambition from what benefitted Rome itself.

When Marius took command he removed the land ownership requirement of serving in the military which had existed until this point. Per Quintus Curtius, “By allowing anyone to sign up - and inevitably making such enlistees dependent on his personally - Marius was establishing a precedent that years later would eventually undermine the Senate’s authority [and pave the way for a transition to Empire].”

Jugurtha was finally captured when his ally, Bocchus I, the king of Mauretaina (modern day Morocco), who together with Jugurtha had lost numerous battles against the Romans, was faced with a stark choice: turn Jugurtha over to Sulla in order to re-ingratiate himself with Rome, or turn Sulla over to Jugurtha as a hostage bargaining chip in order to attempt to end the war that way. Bocchus was torn, undecided at such a momentous decision, but he finally made up his mind. Bocchus chose the side of the Romans and Jugurtha was betrayed and handed over.

The Romans took Jugurtha back to Rome, paraded him in a Triumph for Marius, then threw him into the Tullianum where he was either starved to death or strangled after a number of days.

Numidia was carved up with the western portion going to Bacchus as reward and the eastern part eventually became a Roman province.

Sulla wore a ring for the rest of his life portraying his capture of Jugurtha despite Marius being awarded the credit for it, hinting at their later rivalry which would engulf the Republic and set the stage for Julius Caesar’s ascendancy.

Concluding thoughts

As G. Michael Hopf states, “Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times.” The fact that Jugurtha was able both to rise to power in such an ignoble fashion and then to keep it for so long by bribing Roman Senators and high ranking officials reflected Rome’s moral and ethical decline. Romans sought individualism, power and money at the expense of the state, which led to such instability that it only stabilized by a transition from Republic to Empire. The roots of decline were in Rome’s total victory over Carthage which led to widespread complacency and decadence. Only the constant struggle born from serious challenges can keep virtue from descending into vice. This is an important lesson repeated throughout history but never ultimately learned because the victory over ones enemies always feels so good, like candy before a toothache. Globohomo has been on top for so long, has had it so good since they unambiguously defeated all their enemies, and is richer and more powerful than any nation that has ever come before, so the corresponding decadence which exists today is likely the worst that humanity has ever experienced. Harder times are ahead, but the silver lining is hopefully they can eventually lead to a rebirth of virtue.

Thanks for reading.

The other being Conspiracy of Catiline, which is the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola’s upcoming poorly reviewed epic Megalopolis which looks like a mess per the teaser.

The War of Jugurtha, II: “For as a human being is composed of both a physical form and a soul, all of our earthly pursuits attend to the nature of either the body or the soul. Thus a beautiful body, great riches, physical strength, and all other attributes of this type melt away in a short time; but surpassing deeds of character are, like the soul, eternal. Ultimately the goods of the body and of fortune have both an inception and a conclusion. Everything that has risen falls, and all that is created grows old. But the soul is imperishable, eternal, and the pilot of mankind; it moves and comprehends all things, but is not itself moved.”

From the Conspiracy of Catiline, X: “…and when Carthage, jealous of the Roman Empire, was destroyed root and branch and every land and sea lay open; then, at last, Fortune began to vent her disfavor and all began to become turbulent. Those who had easily borne labors, dangers, insecurity and bitterness now found that leisure and riches - so desirable in some situations - were instead a burden and source of woe. Thus first the love of money grew, and then the love of power as well; these things were essentially the building blocks of all evils. Greed overturned honesty, good faith, and the other positive virtues; in their place it nurtured arrogance, cruelty, neglect of religious duty, and the idea that everything could be bought for a price….after riches began to be considered a substitute for honor, and when glory, power, and force followed as a consequence, virtue grew feeble; humble circumstances were held a disgrace, and innocence began to be regarded with malice. As wealth grew steadily, luxury and greed combined with arrogance took possession of the youth. They freely took what they wanted, consumed with reckless abandon, and placed scant value on their own possessions while coveting those of others; shame, modesty, and all things human and divine were thought of as nothing. There was no sense of moderation.”

As an aside, growing up without parents can be a double-edged sword: the child loses protection and guidance but is free from parental expectations and demands, becoming free to pursue their own ends in their own way. This is why many Disney movies start with the death of the parents (see Bambi, Frozen, Cinderella, Snow White, Tarzan, etc). Back to the Schwarzenegger comparison, compare the physiognomy of Arnold’s carbon-copy bastard son who grew up with little contact with his father with that of his legitimate son. Without having a safety net, perhaps the bastard child instinctively knows he must rely on himself…

The War of Jugurtha, XLII: “After Tiberius and Caius Gracchus, whose ancestors gave so much in service of the republic during the Punic and other wars, began to champion the legal rights of the plebs and reveal the crimes of the wealthy elites, the guilty nobility was dismayed. They put obstacles in the way of the reforms of the Gracchi: they used the allies and the Latin communities of Italy, as well as the Roman knights, who distanced themselves from the plebs out of hope of an alliance with the nobility. First Tiberius was killed violently; then a few years later his brother Caius, who had taken up the same cause, met the same fate. One was a tribune and the other a commissioner for colonies. Marcus Fulvius Flaccus was killed along with them. It must be said, however, that the spirit fo the Gracchi - with its lust for victory - was insufficiently moderate. But a good man would prefer to be defeated rather than eradicate injustice through evil conduct.”

Quintius Curtius had an interesting footnote on this: “This important sentence encapsulates the essence of counterinsurgency operations…Metellus’s strategy throws Jugurtha off his game and takes the initiative away from him. Instead of chasing Jugurtha around, he forces the Numidian to chase him around.”

The Gods expressed their favor for Marius via divination. “By some chance at the same time at Utica a diviner [a trained soothsayer who could ‘read’ the entrails of sacrificed animals for predictions of present and future events'] uttered an extraordinary and momentous prophecy when Caius Marius was sacrificing some animals to the gods: the soothsayer told Marius that he should listen to his inner spirit and conduct himself with trust in the gods; he should put fortune to the test as often as he could with the knowledge that all his enterprises would turn out favorably.” Indeed, he ended up holding the office of consul an unprecedented seven times and died peacefully. Still, Plutarch relates that, ever an ambitious man, Marius lamented on his deathbed that he had not achieved all of which he was capable, despite his achievements.

When I think of Sulla, other than thinking of dictatorship and proscriptions, I think of the inscription on his grave. An epitaph, which Sulla composed himself, was inscribed onto the tomb, reading, "No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full."

Empires are very much like grand stories. In a sense, when you look into it, the end is written in the beginning. Total victory leads to prosperity and comfort and to the height of an empire, but this very situation paves the way for decadence.

Is there something that can be done to prevent this? I don't think so. A good solution would perhaps be a mandate of heaven much like the chinese empire as it would hasten the destruction of the old and decadent in order to give birth to something new. Here again we see the pattern of life & death, birth and rebirth.

Of course our modern situation brings great suffering because technology acts as a amplifier. We have to tolerate abject insults against nature and all things healthy, beautiful and noble because of that, but in the end the pattern is the same.

The parallels between then and now are uncanny. For me personally the 3 greatest issues we are experiencing in this late stage empire decline are social disenegration, resource scarcity (a result of overreliance on outsourcing our manufacturing) and military overextension which drains our resources at home and creates more enemies.

As the old saying goes, "buckle up because it's about to get bumpy".

Thanks again for the great article and the historical relevance of how Rome's decline matches our own.