Julian the Apostate: A doomed struggle against the birth of a new world (Part 1)

Christianity's transvaluation of values and the twilight of the Gods

Emperor Julian, known colloquially as “The Apostate” for being the last Hellenist1 emperor and for his vigorous attempts to reinvigorate the polytheistic Gods of the ancient world, is one of history’s most interesting figures. Despite serving as Emperor for only two years during a period in which the Roman Empire was already in steep decline (361-363 AD), he served as an outsized inspiration in the centuries thereafter for his ill-fated attempt to restore Hellenism during Christianity’s ascendancy. In the preface to his incredible novel “Julian”, Gore Vidal states:

“Julian has always been something on an underground hero in Europe. His attempt to stop Christianity and revive Hellenism exerts still a romantic appeal, and he crops up in odd places, particularly during the Renaissance and again in the nineteenth century. Two such unlikely authors as Lorenzo de’ Medici and Henrik Ibsen wrote plays about him. But aside from the unique adventure of Julian’s life, what continues to fascinate is the fourth century itself. During the fifty years between the accession of Julian’s uncle Constantine the Great and Julian’s death at thirty-two, Christianity was established. For better or worse, we are today very much the result of what they were then.”

What Nietzsche described as the transvaluation of values from Roman warrior values of strength, individuality, self-determination, immediacy of purpose, honor, acceptance of hierarchy and nobility to Christian priestly values of subservience, conformity, equality, pity, guilt, suffering and self-hatred - values ubiquitous in the modern West - were solidified in the fourth century. Julian served as the desperate, final gasp of a dying Hellenism trying to resist the forces which had been set in motion centuries before by Paul. Julian’s struggle holds a romantic appeal because the odds of him prevailing in his attempt were so low, because of his unique blend of warrior and scholar attributes, and because he was the last attempt at resisting Christian slave morality revolution until a failed attempt in the 20th century.2

Not many people know the details of Julian’s life, so I thought I would offer an overview of it. I will quote liberally herein from Vidal’s superbly researched novel. Vidal, although a wealthy patrician (as opposed to a plebian or “prole” i.e. proletariat), homosexual3, and atheist who had a bone to pick with Christianity, was a serious student of history, making extensive use of contemporary sources. Per Vidal, Julian’s “life is remarkably well documented. Three volumes of his letters and essays survive while such acquaintances as Libanius and Saint Gregory of Nazianzus wrote vivid accounts of him. Though I have written a novel, not a history, I have tried to stay with the facts.”4 He eloquently describes a dying ancient world and the birth of a new Christian one, and his novel was written for a mass audience when average IQs were twenty points higher than they are today.5

The purpose of this essay is three-fold:

To provide clarity on the transvaluation of values from Hellenism to Christianity which affects us to this day;

To bring to life, in a small way, a very alien way of living: one focused on animal sacrifice and prayer before multiple Gods, all seen as aspects of the One; on dream interpretation, prophecy and signs from the Gods, often ambiguous and open to interpretation, regularly colored by ego and hidden objectives; and

To demonstrate that when cultural forces reach certain levels, they are extremely difficult to reverse even if one gives a superhuman effort. There are parallels with Donald Trump, who tried to revert America by a couple of decades against the tides of wokeness (supercharged by the Rothschild-owned central banks) swamping and destroying white western civilization. Trump was no Julian, though, and had the heart and soul of a small-minded merchant.

As a caveat, there’s a bit of a feeling of hesitation in describing Julian’s life. The reason for this hesitation is because hyper crypto-Christians in the modern era - secularists, leftists, communists, atheists - have saturated society from top to bottom with attacking Christianity from an even more leftist pro-egalitarian perspective, so it feels on the surface like piling on and joining in their attacks. However, there is little in common between Julian’s life as a reaction to restore Hellenism with those of modern leftists who view the world through a prism of nihilism, materialism and ressentiment.

With that said, let’s begin.

Historical Background

The Roman empire in the fourth century was deep into its process of conversion to Christianity. In the below time-lapsed video you can follow its spread year-by-year since the time of Christ. One can see the enormous changes that occurred when Constantine I “The Great”6 converted in 312AD supposedly after a vision he had at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and imposed the religion throughout the empire7:

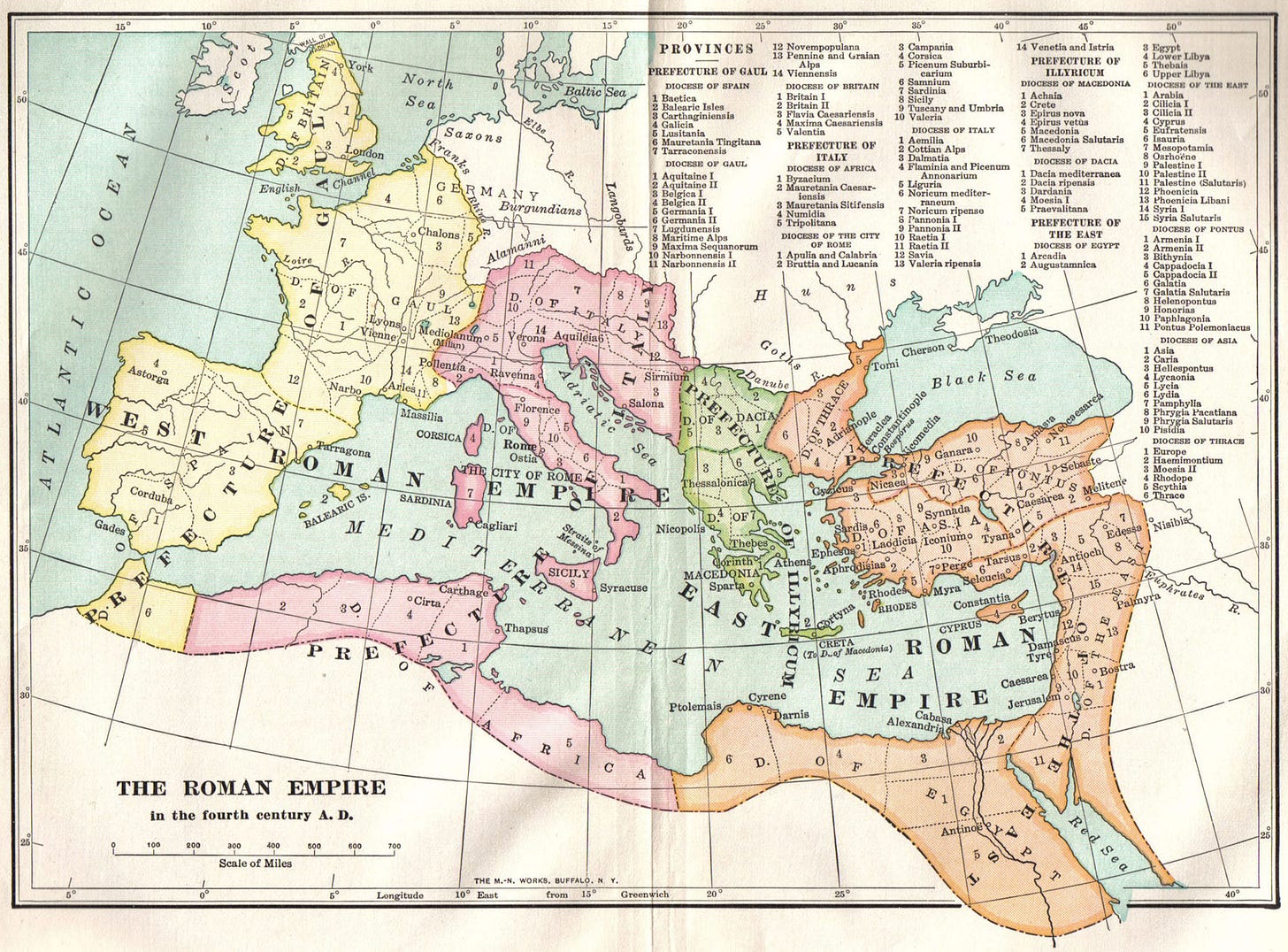

Compare the religion’s spread with the borders of the Roman Empire itself in the 4th century:

A little over ten years after the newly Christian Constantine took power, laws began to be passed restricting “the pollutions of idolatry.” During his reign it was decreed that “no one should presume to set up cult-objects, or practice divination or other occult arts, or even to sacrifice at all.” Under Constantine’s son Constantius II it was ordered that the Hellenist temples were to be closed. In AD 356 it became illegal on pain of death to worship images. “Pagans” began to be described as “madmen” whose beliefs must be “completely eradicated.”8

According to historian Edward J. Watts in “The Final Pagan Generation”,

The ‘final pagan generation’…is made up of the last group of elite Romans…who were born into a world in which most people believed that the pagan public religious order of the past few millennia would continue indefinitely. They were the last Romans to grow up in a world that simply could not imagine a Roman world dominated by a Christian majority. This critical failure of imagination is completely understandable. At the beginning of the second decade of the fourth century there had never been a Christian emperor, and the childhood and early adolescence of members of this generation living in the East coincided with moments when the resources of the Roman state were devoted to the suppression of Christianity. The longest-lived of this group died in an empire that would never again see a non-Christian sovereign, and that no longer financially supported the public sacrifices, temples, and festivals that had dominated Roman life in their youth. They lived through a time of dramatic change that they could neither anticipate nor fully understand as it was unfolding.9

There are easy parallels between this final “pagan'“ generation and the wokeness swamping the West today.

It was into this environment where Julian was born.

Julian’s Early Life as a Christian

Julian was born in 331 into the family of the reigning emperor Constantine I. His father was Constantine's younger half-brother, and his mother was a daughter of a high-ranking bureaucrat who died shortly after his birth.

Constantine’s death set off a power struggle among his sons which was ultimately won by Constantius II, Julian’s cousin. To cement his rule Constantius ordered the murder of Julian’s father and older brother, an uncle, and several cousins, a dozen murders in all, sparing Julian and his half-brother Gallus due to their youth. Constantius jointly ruled the empire with his two siblings until they both suffered untimely ends, leaving him as sole emperor.

Julian grew up under armed guard, always wondering if Constantius was going to change his mind and have him and Gallus executed. Constantius’s Christian beliefs stood in stark contrast to his murderous actions, and planted the first seeds of what became Julian’s antagonism against the religion even as he was rigorously educated in it:

I must have been staring too obviously at the ceiling, for the Bishop [Eusebius] suddenly asked me, “What is the most important of our Lord’s teachings?”

Without thinking, I said, “Thou shalt not kill.” I then rapidly quoted every relevant text from the new testament (much of which I knew by heart) and all that I could remember from the old. The Bishop had not expected this response. But he nodded appreciatively. “You have quoted well. But why do you think this commandment the most important?”

“Because had it been obeyed my father would be alive.” I startled myself with the quickness of my own retort.

The Bishop’s pale face was even ashier than usual. “Why do you say this?”

“Because it’s true. The Emperor killed my father. Everybody knows that. And I suppose he shall kill Gallus and me, too, when he gets around to it.” Boldness, once begun, is hard to check.

“The Emperor is a holy man,” said the Bishop severely. “All the world admires his piety, his war against heresy, his support of the true faith.”

This made me even more reckless. “Then if he is such a good Christian how could he kill so many members of his own family? After all, isn’t it written in Matthew and again in Luke that…”

“You little fool!” The Bishop was furious. “Who has been telling you these things? [Your tutor] Mardonius?

I had sense enough to protect my tutor. “No, Bishop. But people talk about everything in front of us. I suppose they think we don’t understand. Anyway it’s all true, isn’t it?”

The Bishop had regained his composure. His answer was slow and grim. “All that you need to know is that your cousin, the Emperor, is a devout and good man, and never forget that you are at his mercy.” The Bishop then made me recite for four hours, as punishment for impudence. But the lesson I learned was not the one intended. All that I understood was that Constantius was a devout Christian. Yet he had killed his own flesh and blood. Therefore, if he could be both a good Christian and a murderer, then there was something wrong with his religion. Needless to say, I no longer blame Constantius’s faith for his misdeeds, any more than Hellenism should be held responsible for my shortcomings! Yet for a child this sort of harsh contradiction is disturbing, and not easily forgotten.

Julian’s faith in Christianity was further shaken by the Arian crisis, where Christians murdered each other en masse in a dispute over the Nicene Creed regarding whether Christ was of the same substance (Homoousion), or of a similar substance (Anomoeanism) to God. In a walk around the city with Gallus and their tutor Mardonius, they watched two old men get beaten up by a dozen monks armed with sticks who shouted all the while, “Heretic! Heretic!”

“But aren’t they all Christians?” I asked. “Don’t they believe in Jesus and the gospels?”

“No!” said Gallus.

“Yes,” said Mardonius. “They are Christians, too. But they are in error.”

Even as a child I had a reasonably logical mind. “But if they are Christians, like us, then we must not fight them but turn the other cheek, and certainly nobody must kill anybody, because Jesus tells us that…”

“I’m afraid it is not as simple as all that,” said Mardonius. But of course it was. Even a child could see the division between what the Galileans say they believe and what, in fact, they do believe, as demonstrated by their actions. A religion of brotherhood and mildness which daily murders those who disagree with its doctrines can only be thought hypocrite, or worse.

In a culture that was still somewhat polytheistic and rooted in a tremendously long history of religious tolerance, Hellenists were astonished at how narrow-minded and intolerant the Christians were. To Christians Jesus was the way, the truth and the light, and every other religion along with the Christians who believed the wrong doctrines were not merely wrong but plunged its followers into a demonic darkness which risked eternal damnation. To allow someone to continue in an alternative form of worship or a heretical form of Christianity was not to allow religious freedom; it was to allow Satan to thrive.10

At the same time young Julian was drawn to learning about the old Gods:

Some months later when Mardonius and I were alone together in the palace gardens overlooking the Bosphorus, I questioned him about the old religion. I began slyly: was everything Homer wrote true?

“Of course! Every word!”

“Then Zeus and Apollo and all the other gods must exist, because he says they do. And if they are real, then what became of them? Did Jesus destroy them?”

Poor Mardonius! He was a devoted classicist. He was also a Galilean. Like so many in those days, he was hopelessly divided. But he had his answer ready. “You must remember that Christ was not born when Homer lived. Wise as Homer was, there was no way for him to know the ultimate truth that we know. So he was forced to deal with the gods the people had always believed in…”

“False gods, according to Jesus, so if they’re false then what Homer writes about them can’t be true.”

“Yet like all things, those gods are manifestations of the true.” Mardonius shifted his ground. “Homer believed much as we believe. He worshipped the One God, the single principle of the universe. And I suspect he was aware that the One God can take many forms, and that the gods of Olympus are among them. After all, to this day God has many names because we have many languages and traditions, yet he is always the same.”

As Julian and Gallus grew they continued to fear that they would be executed by Constantius, but Constantius and his wife Eusebia were unable to have children (the rumor was it was a curse from the Gods because he killed so many of his family members) and they were kept alive because they were the last of the family line.

Although he continued to be schooled in Arianism, Julian preferred philosophy to religion and he was introduced to the works of Plotinus and Porphyry, who wrote the famous work “Against the Christians” which was later censored and every copy burnt (Julian would later copy him with his own “Against the Galileans”), and became close personal friends with the physician Oribasius.

Eventually Constantius allowed Julian to study philosophy in Constantinople, separating from Gallus. Constantius’s nefarious Grand Chamberlain Eusebius studied Julian carefully and concluded he was harmless: “At seventeen I was the worst sort of Sophist. This probably saved my life. I bored Eusebius profoundly and we never fear those who bore us. By definition, a bore is predictable. If you think you know in advance what a man is apt to say or do, you are not apt to be disagreeably surprised by him. I am sure that in that one interview I inadvertently saved my life.”

Julian’s Conversion to Mithraism

In January 350 Julian received permission to move to Pergamon to stay with Oribasius, whose friendship with Julian was a well-kept secret. Oribasius then brought Julian to see Sosipatra, a Neoplatonist philosopher and mystic:

When we arrived at her house, Sosipatra came straight to me, knowing exactly who I was without being told. “Most noble Julian, welcome to our house. And you too, Ecebolius [Julian’s guard and instructor]. Oribasius, your father sends you greetings.”

Oribasius looked alarmed, as well he might: his father had been dead three months. But Sosipatra was serious. “I spoke to him just now. He is well. He stands within the third arc of Helios, at a hundred-and-eighty-degree angle to the light. He advises you to sell the farm in Galatria. Not the one with the cedar grove. The other. With the stone house. Come in, most noble prince. You went to see Aedesius today but his wife turned you away. Nevertheless, my old friend will see you in a few days. He is sick at the moment but he will recover. He has four more years of life. A holy, good man.”

Priscus and Libanius, reading Julian’s journal retrospectively, had differing takes on Sosipatra: Priscus thought she was a boring, tedious, and a monster, but “a remarkable magician. Even I came close to believing in her spells and predictions. She also had a sense of drama which was most exciting. Julian was completely taken in by her, and I date his fatal attraction to this sort of thing from that dinner party”, while Libanius thought she talked too much. Julian’s meeting with Sosipatra continued:

When the sons had withdrawn, Sosipatra sent for a tripod and incense. “And now you will want to know what the gods advise you to do. Where to go. With whom to study.” She gave me a dazzling smile.

I blurted out, “I want to study here, with you.” But she shook her head, to Ecebolius’s relief. “I know my own future and a prince is no part of it. I wish it were otherwise,” she added softly, and I fell in love with her on the spot, as so many students had done before me.

Sosipatra lit the incense. She shut her eyes. She whispered a prayer. Then in a low voice she implored the Great Goddess to speak to us. Smoke filled the room. All things grew vague and indistinct. My head began to ache. Suddenly in a loud voice not her own, Sosipatra said, “Julian!”

I looked at her closely. Her eyes were half open but only the whites showed: she slept while the spirit possessed her. “You are loved by us beyond any man alive.” That was puzzling. “Us” must mean the gods. But why should they love a Galilean who doubted their existence? Of course I had also begun to question the divinity of the Nazarene, which made me neither Hellenist nor Galilean, neither believer nor atheist. I was suspended somewhere between, waiting for a sign. Could this be it?

“You will rebuild our temples. You will cause the smoke of a thousand sacrifices to rise from a thousand altars. You shall be our servant and all men shall be your servants, as toke of our love.”

Ecebolius stirred nervously. “We must not listen to this,” he murmured.

The voice continued serenely. “The way is dangerous. But we shall protect you, as we have protected you from the hour of your birth. Earthly glory shall be yours. A and death when it comes in far Phrygia, by enemy steel, will be a hero’s death, without painful lingering. Then you shall be with us forever, close to the One from whom all light flows, to whom all light returns. Oh, Julian, dear to us…Evil!” The voice changed entirely. It became harsh. “Foul and profane! We bring you defeat. Despair. The Phrygian death is yours. But the tormented soul is ours forever, far from light!”

Sosipatra screamed. She began to writhe in her chair; her hands clutched at her throat as though to loosen some invisible bond. Words tumbled disjointedly from her mouth. She was a battle-ground between warring spirits. But at last the good prevailed, and she became tranquil.

“Ephesus,” she said, and her voice was again soft and caressing. “At Ephesus you will find the door to light.”

Sosipatra continued, confirming various secrets to the participants that no one else could have known. She said that Julian was to restore the worship of the true gods, that the goddess Cybele was his protectress, and at Ephesus Julian would meet and be instructed by Maximus, another Neoplatonist philosopher known to be a magician.11 She said to Ecebolius, “He has no choice, you know. At Ephesus his life begins.”

Priscus, reading Julian’s journal, believes this meeting was a well-planned plot, to which Libanius agreed:

They were all in on it. Years later, Maximus admitted as much. “I knew all along I was the right teacher for Julian. Naturally, I never dreamed he would be emperor”…Maximus then got Sosipatra and Aedesius to recommend him to Julian, which they did. What an extraordinary crew they were! Except for Aedesius, there was not a philosopher in the lot.

From what I gather, Julian in those days was a highly intelligent youth who might have been “captured” for true philosophy. After all, he enjoyed learning. He was good at debate. Properly educated, he might have been another Porphyry or, taking into account his unfortunate birth, another Marcus Aurelius. But Maximus got to him first and exploited his one flaw: that craving for the vague and incomprehensible which is essentially Asiatic.

Julian traveled to Ephesus where he went to the magician Maximus’s house, which was on the slopes of Mount Pion; a hidden door led into the mountain itself where he met Maximus in a cave filled with natural smoke. Instead of doing tricks, though, Maximus offered up a shrewd attack on Christianity:

“In letters to the Romans and to the Galatians, Paul declared that the god of Moses is the god not only of Jews but also of Gentiles. Yet the Jewish book denies this in a hundred places. As their god says to Moses: “Israel is my son, my first-born.” Now if this god of the Jews were indeed, as Paul claimed, the One God, why then did he reserve for a single unimportant race the anointing, the prophets and the law? Why did he allow the rest of mankind to exist thousands of years in darkness, worshipping falsely? Of course the Jews admit that he is a ‘jealous god.’ But what an extraordinary thing for the absolute to be! Jealous of what? And cruel, too, for he avenged the sins of the fathers on guiltless children. Is not the creator described by Homer and Plato more likely? That there is one being who encompasses all life - is all life - and from this essential source emanates gods, demons, men? Or to quote the famous Orphic oracle which the Galileans are beginning to appropriate for their own use, '‘Zeus, Hades, Helios, three gods in one Godhead.’”

“From the One many…” I began, but with Maximus one never needs to finish sentences. He anticipates the trend of one’s thought.

“How can be the many be denied? Are all emotions alike? Or does each have characteristics peculiarly its own? And if each race has its own qualities, are not those god-given? And, if not god-given, would not these characteristics then be properly symbolized by a specific national god? In the case of the Jews a jealous bad-tempered patriarch. In the case of the effeminate, clever Syrians, a god like Apollo. Or take the germans and the Celts - who are warlike and fierce - is it accident that they worship Ares, the war god? Or is it inevitable? The early Romans were absorbed by lawmaking and governing - their gods? The king of Gods, Zeus. And each god has many aspects and many names, for there is as much variety in heaven as there is among men. Some have asked: did we create these gods or did they create us? That is an old debate. Are we a dream in the mind of diety, or is each of us a separate dreamer, evoking his own reality? Though one may not know for certain, all our senses tell us that a single creation does exist and we are contained by it forever. Now the Christians would impose one final rigid myth on what we know to be various and strange. No, not even myth, for the Nazarene existed as flesh while the gods we worship were never men; rather they are qualities and powers become poetry for our instruction. With the worship of the dead Jew, the poetry ceased. The Christians wish to replace our beautiful legends with the police record of a reforming Jewish rabbi. Out of this unlikely material they hope to make a final synthesis of all the religions ever known. They now appropriate our feast days. They transform local deities into saints. They borrow from our mystery rites, particularly those of Mithras. The priests of Mithras are called ‘ fathers.’ So the Christians call their priests ‘fathers’. They even imitate the tonsure, hoping to impress new converts with the familiar trappings of an older cult. Now they have started to call the Nazarene ‘savior’ and ‘healer.’ Why? Because one of the most beloved of our gods is Asklepios, whom we call ‘savior’ and ‘healer’….

I betray no secret of Mithras when I tell you that we, too, partake of a symbolic meal, recalling the words of the Persian prophet Zarathustra, who said to those who worshipped the One God - and Mithras, ‘He who eats of my body and drinks of my blood, so that he will be made one with me and I with him, the same shall not know salvation. That was spoken six centuries before the birth of the Nazarene….As [Zarathustra] lay dying, he said, ‘May God forgive you even as I do."‘ No, there is nothing sacred to us that the Galileans have not stolen….

No one can tell another man what is true. Truth is all around us. But each must find it in his own way. Plato is part of the truth. So is Homer. So is the story of the Jewish god if one ignores its arrogant claims. Truth is wherever man has glimpsed divinity. Theurgy can achieve this awakening. Poetry can. Or the gods themselves of their own volition can suddenly open our eyes.”

Priscus thinks Maximus’s strategy here was a shrewd one: “Then he offers Julian Mithras, a religion bound to appeal to our hero. Mithras was always the favorite deity of Roman emperors, and of many soldiers to this day. Also, Maximus knew that he would be sure of a special relationship to Julian if he were the one who sponsored him during the rites.” Julian agreed with Maximus and asked to take the secret initiation rites into Mithraism; he said he would publicly pretend to be Christian as that was required of him by Constantius. On the day of his initiation he found out that his half-brother Gallus had been risen to Caesar of the East by Constantius (the rank of Caesar was one below that of Emperor). Julian was nineteen years old.

***

Part 2 explores Julian’s path to becoming Emperor, his initiation into the mysteries of Eleusis, his pro-Hellenist reforms, his downfall, and contextualize his rule in a historical setting, explaining how the lessons of Julian’s life remain relevant today as the horrors of wokeness threaten to subsume western civilization itself.

“Pagan” was a Christian term of contempt for Hellenists, meaning “rural” or “rustic”, because the rural areas are always last to adopt the new ideologies fermented in metropolitan areas. The term Hellenist will be used in this essay as a neutral label unless quoting from another source that uses the term pagan.

Indeed, Hitler was a big fan of Julian for his attempt to prevent the original transvaluation of values, where he stated in his Table Talks: “When one thinks of the opinions held concerning Christianity by our best minds a hundred, two hundred years ago, one is ashamed to realise how little we have since evolved. I didn't know that Julian the Apostate had passed judgment with such clear-sightedness on Christianity and Christians….It would be better to speak of Constantine the traitor and Julian the Loyal than of Constantine the Great and Julian the Apostate.”

In the context of Vidal’s homosexuality and his writings on the ancient world I cannot help but think of the graffiti on the walls of Pompeii, which read “Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men’s behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!”

Also see the letters from a World War 2 soldier about to be executed; the cumulative dysgenic effects of only a couple of generations are astonishing.

Note that the labeling of Constantine as “The Great” (despite murdering his wife — he allegedly boiled her in a bath because of a suspected affair with his son and converted to Christianity because the priests of the old Gods said he was too polluted to be purified of these crimes, per Catherine Nixey in “The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World”, 100) is precisely in the context of victorious Christian history, as is Julian’s “The Apostate”.

This is a very important battle in another context, as it spelled the final defeat and the disbanding of the Praetorian Guard which had been the true power behind the Emperors for centuries; something that may be discussed further in a future post, as its parallels to the modern day FBI, CIA and DOJ are many.

Nixey, 117.

Edward J. Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, 6.

Nixey, 48.

Maximus hid from Julian during Julian’s civil war with Constantius, which Julian was expected to lose, then showed up after Julian won. Later after the Persian campaign when Maximus was in trouble, he and his wife decided to commit suicide. She killed herself, then Maximus changed his mind and lived for awhile longer. Around 370, Emperor Valens was informed that a group of individuals had consulted an oracle to find out who the next emperor would be, and were told that Valens would be succeeded by a man whose name began with the letters Theod. (which turned out to be true). Maximus was then executed, but he warned that whoever executed him would suffer a terrible fate and a cruel death, which then befell Valens.

The Old Testament said YHWH was for many peoples, not just the Jews. Samaritans, Persians, Midians, and Jonah was even sent on a conversion mission. The difference for the Samaritans and Jews was that God loved Abraham, so he blessed his descendants. The Jews priesthood was then shut down because they murdered the son of YHWH.

The bible said the God of the Persians was the God of Abraham. The Persians even paid the Jews to sacrifice to the God (YHWH) of Persia and Jews, at the Temple. The Mithra cult was way, way off from the early Zoroastrian Gathas which was very Monotheistic.

Christianity was never meant to rule in the world. After Constantine, the devout Christians complained the official Church became filled with opportunists and crooks looking to live off the treasury.

Christ was killed by the then official priesthood, as if he was a heretic. The bible is a history of prophets warning the authorities, and being persecuted for it.

Christ equally went to the Samaritans, who were the enemies of the Jews, because Samaritans are the Northern House of Israel. Christ got the Jews mad for speaking well of the Samaritans.

The New Testament said there were many gods, such as the Devil being the god of the world.

Julian's argument seems to be the religion of fake Christians is wrong, so Christianity is wrong.

Christians are called weak, but they ended up ruling the world by 1900, by conquering the Pagans.