Julian the Apostate: A doomed struggle against the birth of a new world (Part 2)

Christianity's transvaluation of values and the twilight of the Gods

Continued from Part 1…

Julian’s Path to Emperor

As Julian studied philosophy and religion, his half-brother Gallus ruled the East as a tyrant. He and his wife Constantina, the sister of Constantius, were eager to amass a fortune, and they used blackmail, the sale of public offices, and confiscation of assets to get it. They were bloodthirsty and terrorized, raped and murdered the population over whom they ruled even as Gallus professed to be a serious believer in Christ (Constantina oddly became venerated as a Christian saint in the Middle Ages based on rumors that had nothing to do with the historical record).

However, a food shortage in Gallus’s territory grew worse and his attempts at price fixing failed. The population was on the verge of revolt. Constantius realized he had to recall Gallus or risk wider unrest, but having had much experience defeating threats to his rule - avoiding war with his co-Emperor brothers, murdering family members, then successfully destroying the attempted usurpation of Magnentius, Vetranio, and Silvanus - he proceeded cautiously. Constantina traveled to Constantius to try to avert civil war but she died on the way, severing the main link between the two relatives. Gallus was recalled by Constantius after taking measures to ensure he could not rebel and then executed.

Julian, fearful he would murdered next, joined a religious order at Nicomedia in an attempt to hide, but he was discovered, arrested, and then held for six months incommunicado at Como. The Grand Chamberlain eunuch Eusebius called for Julian’s execution; Constanius’s wife Euseiba argued that he was the last of their line and must be spared on that basis. He was ultimately spared in a close call and allowed to continue his studies at Athens.

When he reached Athens, Julian noticed the decline of Greece compared to ancient times:

As a race, [the Greeks] are much changed. They are no longer noble. They have been too often enslaved, and their blood mixed with that of barbarians. Yet I do not find them as sly and effeminate as certain Latin writers affect to. I think that the Old Roman tendency to look down on the Greeks is no more than a natural resentment of Greece’s continuing superiority in those things which are important: philosophy and art. All that is good in Rome today was Greek. I find Cicero disingenuous when on one page he acknowledges his debt to Plato and then on the next speaks with contempt of the Greek character. He seems unaware of his own contradictions…doubtless because they were a commonplace in his society.

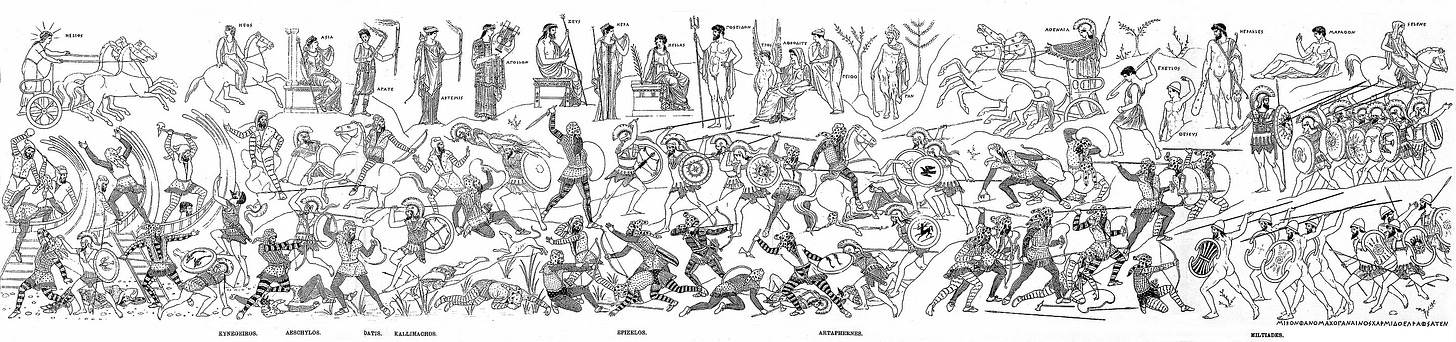

As Julian looked at the eight hundred year old Painted Portico of the Battle of Marathon, he commented:

These young men and their slaves - yes, for the first time in history slaves fought beside their masters - together saved the world. More important, they fought of their own free will, unlike our soldiers, who are either conscripts or mercenaries. Even in times of peril, our people will not fight to protect their country. Money, not honor, is now the source of Roman power. When the money goes, the state will go. This is why Hellenism must be restored: to instill again in man that sense of his own worth which made civilization possible, and won the day at Marathon.

Julian then met with Prohaeresius, one of the leading rhetoricians and teachers of the era. Prohaeresius was cagey about his own beliefs, but he told Julian he would become Emperor based on the prophecy of an oracle. Using oracles to inquire about future Emperors was forbidden by law and punishable by death; it’s easy to see how such prophecy could undermine the authority of the current Emperor.

“Is it predicted?” I was as bold as he. I incriminated myself, hoping to prove to him my own good faith.

He nodded. “Not the day, not the year, merely the fact. But it will be tragedy.”

“For me? Or for the state?”

“No one knows. The oracle was not explicit.” He smiled. “They seldom are. I wonder why we put such faith in them….Now it my guess, Julian, that you mean to restore the worship of the old gods.”

My breath stopped. “You presume too much.” My voice shook despite a hardness of tone which would have done justice to Constantius himself. Sooner or later one learns the Caesarian trick: that abrupt shift in tone which is harsh reminder of the rod and axe we wield over all men.

“I hope that I do,” said the old man, serenely.

“I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have spoken like that. You are the master.”

He shook his head. “No, you are the master, or will be soon. I want only to be useful. To warn you that despite what your teacher Maximus may say, the Christians have won.”

“I don’t believe it!” Fiercely and tactlessly I reminded him that only a small part of the Roman population was actually Galilean….Most of the civilized world is neither Hellenist nor Galilean, but suspended in between. With good reason, a majority of the people hate the Galileans. Too many innocents have been slaughtered in their mindless doctrinal quarrels. I need only mention the murder of Bishop George at Alexandria to recall vividly to those who read this the savagery of that religion not only toward its enemies (whom they term “impious”) but also toward its own followers….

Like so many, [Prohaeresius] is in a limbo between Hellenism and the new death cult. Nor do I think he is merely playing it safe. He is truly puzzled. The old gods do seem to have failed us, and I have always accepted the possibility that they have withdrawn from human affairs, terrible as that is to contemplate. But mind has not failed us. Philosophy has not failed us. From Homer to Plato to Iamblichos the true gods continue to be defined in their many aspects and powers: multiplicity contained by the One, all emanating from truth. Or at Plotinus wrote: “Of its nature the soul loves God and longs to be at one with him.”….

“I see it differently. That is all. But try to be practical. The thing has taken hold. The Christians govern the world through Constantius. They have had almost thirty years of wealth and power. They will not surrender easily. You come too late, Julian. Of course if you were Constantine and this were forty years ago and we were pondering these same problems, then I might say to you: “Strike! Outlaw them! Rebuild the temples!” But now is not then. You are not Constantine. They have the world. The best one can hope to do is civilize them. That is why I teach. That is why I can never help you.”

Julian also met with the Hierophant of Greece when he was in Athens, who was the holiest of men and the custodian and interpreter of the mysteries of Eleusis which went back at least 2,000 years or more. Julian told him he wanted to be initiated into all the mysteries: the lesser, the greater, and the highest. He told the Hierophant that it was his hope to support Hellenism in its war with the Galileans.

[The Hierophant] was abrupt. “It is too late,” he said, echoing Prohaeresius. “Nothing you can do will change what is about to happen.”

I was not expecting such a response. “Do you know the future?”

“I am Hierophant,” he said simply. “The last Hierophant of Greece. I know many things, all tragic.”

I refused to accept this. “But how can you be the last? Why, for centuries…”

“Prince, these things are written at the beginning. No one may tamper with fate. When I die, I shall be succeeded not by a member of our family but by a priest from another sect. He will be in name, but not in fact, the final Hierophant. Then the temple at Eleusis will be destroyed - all the temples in all of Greece will be destroyed. The barbarians will come. The Christians will prevail. Darkness will fall.”

“Forever?”

“Who can say? The goddess has shown me no more than what I have told you. With me, the true line ends. With the next Hierophant, the mysteries themselves will end….Whether you are Emperor or not, Eleusis will be in ruins before the century is done.”

I looked at him closely…despite his terrible conviction, this small fat man with his protuberant eyes and fat hands was perfectly composed. I have never known such self-containment, even in Constantius.

“I refuse to believe,” I said at last, “that there is nothing we can do.”

He shrugged. “We shall go on as long as we can, as we always have.” He looked at me solemnly. “You must remember that because the mysteries come to an end makes them no less true. Those who were initiated will at least be fortunate in the underworld. Of course one pities those who come after us. But what is to be must be….I shall instruct you myself. We shall need several hours a day. Come to my house tonight.” With a small bow he withdrew.

Julian was initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, and would be the last Roman emperor to experience it. Priscus wrote years later that “The Hierophant liked [Julian] but thought he was doomed, or so he told me years later. The Hierophant was an interesting man….he realized with extraordinary clarity that our old world was ended. There were times I think he took pleasure in knowing he was the last of a line that extended back two thousand years. Men are odd. If they cannot be first, they don’t in the least mind being last.”

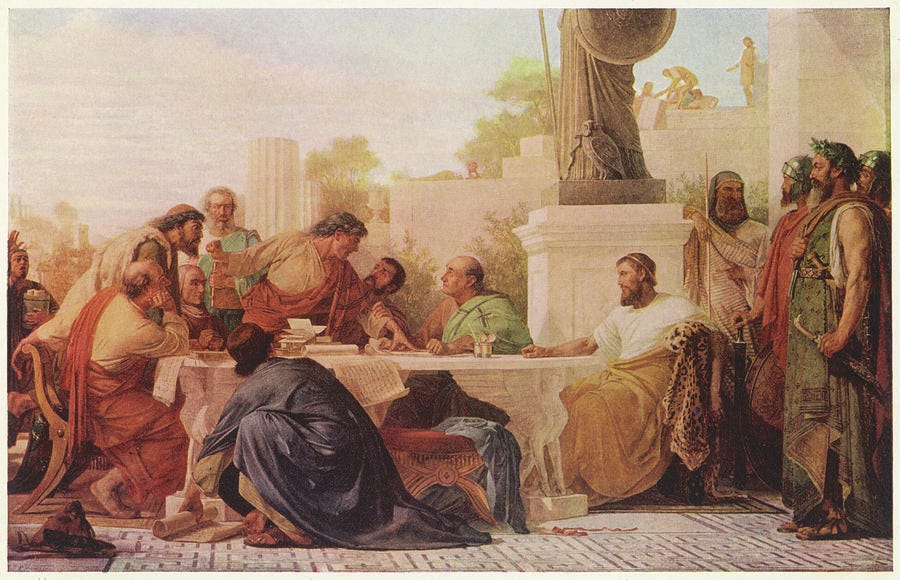

Julian was then raised up by Constantius to be Caesar of Gaul (modern day France); again, it was a close call. Eusebia advocated on his behalf whereas the eunuch Eusebius wanted him put to death. Constantius explained the reason for rising Julian up:

“The world is too big for one person to govern it.” My heart beast faster for I knew now what was to come. “I cannot be everywhere. Yet the imperial power must be everywhere. Things have a habit of going wrong all at once. As soon as the German tribes get loose in the north, the Persians attack in the south. At times I think they must plan it. If I march to the East, I’m immediately threatened in the West. If one general rises up against me, then I must deal with at least two more traitors at the same time. The empire is big. Distances are great. Our enemies many.”

Constantius then married Julian to his ugly sister Helena who was a decade older and who looked like a man. “Helena was a good woman but our moments of intimacy were rare, unsatisfactory, and somewhat pathetic, for I did want to please her. It was never pleasant, making love to a bust of Constantine.” Helena was ultimately pregnant twice, and even though Eusebia had saved Julian’s life, she had Helena’s two pregnancies secretly terminated (one via medicine resulting in miscarriage, one by having the midwife cut the umbilical cord of the newborn too deep) out of worry it would result in Constantius divorcing her and finding another wife who could have children. Nasty business, imperial succession…

Julian was raised up to Caesar on November 6, 355, then sent to Gaul to battle the roaming German bands despite never having a day of combat experience or training. Constantius also tried to undermine him at every turn, subjecting him to the authority of others, cutting his funds, reducing his troops to a minimum, and having him constantly spied on. “Constantius sent me here to die. That’s why I was given no army,” he complained. Julian turned out to be an excellent soldier and general, though, and he ended up evicting the Germans from Gaul and won a famous battle at the Battle of Strasbourg, which earned Constantius’s envy and jealousy.

Eusabia, Julian’s protector in the court, then died. Constantius, who was at war with King Sapor of Persia (but who refused to take action in such war), ordered Julian to send most of his troops, including his best troops, to Constantius. This created a major dilemma for Julian: he had promised his Gallic troops that they would not be sent outside of Gaul, and he also would not have enough troops to defend Gaul from the Germans if he sent the troops away. Furthermore, Julian had heard that one of Constantius’s generals who hated Julian would be given control of Gaul as soon as Julian sent out the troops. Was it another set-up to overthrow Julian like Constantius overthrew Gallus?

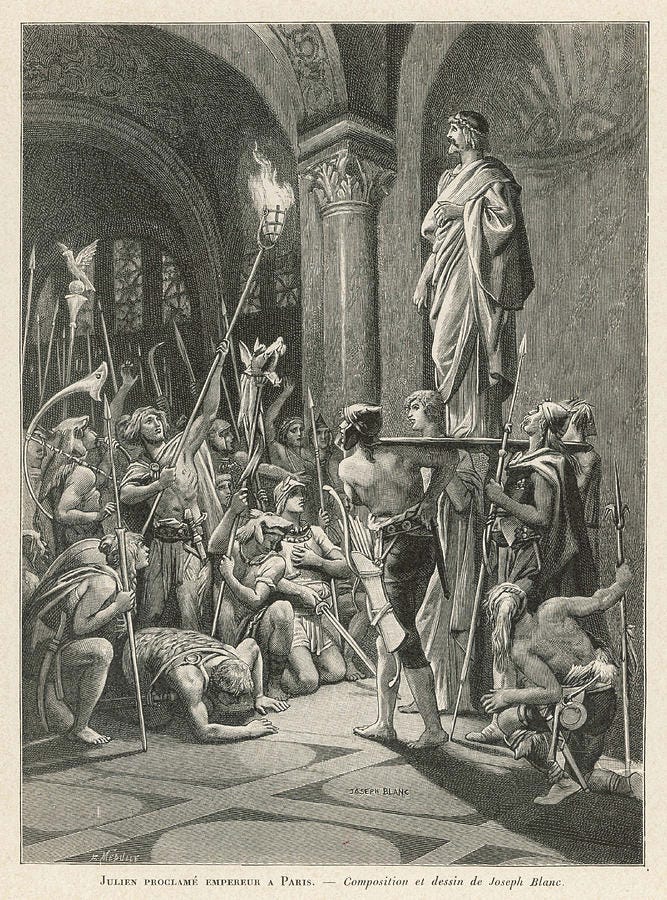

Julian’s Gallic troops, furious at the thought of being sent abroad, forced his hand and proclaimed him Emperor; if he did not accept he could be torn to pieces by the mob. His wife/Constantius’s sister told him to accept; she was still furious over Eusebia’s murder of her two children. Julian had great reluctance, though: Constantius had a much bigger army and had much experience crushing usurpers.

The final factor in favor was a dream Julian had as he slept, still uncertain:

I dreamed and, as often happens, I found in dreaming what I must do awake. I was seated in my consular chair, quite alone, when a figure appeared to me, dressed as the guardian spirit of the state, so often depicted in the old Republic. He spoke to me. “I have watched you for a long time, Julian. And for a long time I have wished to raise you even higher than you are now. But each time I have tried, I have been rebuffed. Now I must warn you. If you turn me away again, when so many men’s voices are raised in agreement with me, I shall leave you as you are. But remember this, if I go now, I shall never return.”

Julian awoke in a cold sweat. He made up his mind and accepted the title of Emperor from the troops.

Julian was mild in his written communication with Constantius and signed his letters to him as Caesar and not Emperor. According to Priscus, “Julian was determined to be merciful [to Constantius’s allies]. He saw himself in the line of Marcus Aurelius. Actually, he was greater than that self-consciously good man. For one thing, he had a harder task than his predecessor. Julian came at the end of a world, not at its zenith. That is important, isn’t it…? We are given our place in time as we are given our eyes: weak, strong, clear, squinting, the thing is not ours to choose.” Constantius bribed his way out of the Persia war and turned his attention to Julian.

Julian had been consulting the oracles and sacred books and making sacrifices to the Gods; all signs agreed that he would prevail and that Constantius would fall. “Yet I did not neglect the practical. Every prophecy is always open to interpretation and if it turns out that its meaning was other than what one thought, it is not the fault of the gods but of us who have misinterpreted their signs. Cicero has written well on this. I particularly credit dreams, agreeing with Aristotle that important messages from heaven are often sent to men as they sleep.” The guardian deity of Rome came to Julian in another dream and spoke very plainly, in verse, that he would win, and a friendly priest consulted the Sibylline books at Julian’s request and according to the secret report Julian would be the next Emperor with a stormy but long reign (the latter part of which turned out to be wrong, assuming it wasn’t a lie to placate Julian).

Julian moved against Constantius into Illyricum, but Constantius bribed two of his legions to switch loyalties at a key location. Constantius’s army was three times the size of Julian’s and moving toward him. Julian was in despair, but then the news came:

Constantius was dead.

Constantius had died of a fever. There were many omens he had experienced - waking dreams and nightmares, among other signs (such as Constantius seeing a headless man facing west strung up on the road they traveled on) that he was about to lose power and die. “Shortly afterwards, when we came to Antioch, the Emperor told Eusebius that he had a sense that something which had always been with him was gone.” “The Spirit of Rome. These are the signs,” Julian said.

Perhaps Constantinus was poisoned. Regardless, he proclaimed Julian the legitimate emperor in his last will and testament as the last surviving member of his bloodline. Julian was now sole and legitimate Emperor of Rome.

Julian’s Pro-Hellenic Reforms as Emperor

As Emperor Julian made a host of changes, some of which are as follows:

He immediately made worship of the old gods legal and acceptable.

He instituted treason trials against some of his enemies, such as the eunuch Eusebius who was executed.

He fired the imperial eunuchs and much of the imperial staff who were dramatically overpaid.

He directed funds for rebuilding and restoration of the old temples which were in extreme disrepair and neglect.

He removed the tax exemption from “Galilean” (his term for Christian) priests, and insisted that all lands and buildings which had been seized by the Galileans be restored (Constantinople contained a tremendous amount of items looted by the Christians from Hellenist temples and properties).

He declared religious freedom to all, which set the Arians and Athanasians against each other again.

He issued another edict which removed the right of the bishops to use public transport at the state’s expense.

Because one of Christianity’s major advantages over Hellenism was its centralized system of regional Bishops, Julian planned to copy that model and institute similar centralization for Hellenism: “I suggest we fight them on their own ground. I plan a world priesthood, governed by the Roman Pontifex Maximus. We shall divide the world into administrative units, the way the Galileans have done, and each diocese will have its own hierarchy of priests under a single high priest, responsible to me.”

Julian also wanted to put a stop to the Christian’s theft of Hellenic rites and holy days by preventing their teaching Latin instead of Greek to students. Among other things this meant that most of the teachers in the schools were Christians. Julian’s solution was to abolish the Latin curriculum and make the schools all teach Greek again, forbidding Christians from teaching.

He removed all Galileans from the Scholarian Guard and refused to allow any Galilean to be governor of a province.

He removed the cross from all military and civic insignia, as well as from the coins he minted, substituting instead images of the gods.

He also took direct charge of the army with his loyal Mithraic Gallic troops at its core, which allowed him to dominate the army.

He exiled noted Christian leader Athanasius, who when told of his exile responded famously, “It is a little cloud which will soon pass.”

He also wanted to institute Hellenic almsgiving to compete with Christian almsgiving:

One reason why the Galileans grow ever more powerful and dangerous to us is their continual assimilation of our rites and holy days. Since they rightly regard Mithraism as their chief rival, they have for some years now been taking over various aspects of the Mithraic rite and incorporating them into their own ceremonies. Some critics believe that the gradual absorption of our forms and prayers is fairly recent. But I date it from the very beginning. In at least one of the biographies of the Galileans there is a strange anecdote which his followers are never able to explain (and they are usually nothing if not ingenious at making sense of nonsense). The Galilean goes to a fig tree to pick its fruit. But as it is not the season for bearing, the tree was barren. In a fit of temper, the Galilean blasts the tree with magic, killing it. Now the fig tree is sacred to Mithras: as a youth, it was his home, his source of food and clothing. I suggest that the apologist who wrote that passage in the first century did so deliberately, inventing it or recording it, no matter which, as a sign that the Galilean would destroy the worship of Mithras as easily as he had destroyed the sacred tree….

I set about reorganizing…no, organizing Hellenism. The Galileans have received much credit for giving charity to anyone who asks for it. We are now doing the same. Their priests impress the ignorant with their so-called holy lives. I now insist that our priests be truly holy. I have given them full instructions on how to comport themselves in public and private.”

One may note that Julian’s attempts to centralize Hellenism and provide almsgiving to compete with Christianity were still (1) steps along the route toward ever-increasing centralization, as on a historical timeline centralization always beats decentralization; and (2) steps toward Nietzsche’s transvaluation of values toward a focus on the poor and destitute, which was simply not a focus under a system of pure warrior values. Historian Tom Holland believes Christianity impacted Julian’s value system more than he cared to acknowledge publicly or even probably to himself.1

Priscus and Libanius both thought that Julian didn’t go hard enough against the Christians, that Julian preferred to debate and negotiate with them instead of use violence: “In a way, it was a pity that he was not a Tiberius, or even a Diocletian. Had he turned butcher, he might have got his way…an emperor whose sole intent is their destruction might succeed through violence, especially if he were at the same time creating an attractive alternate religion. But Julian had made up his mind that he would be a true philosopher. He would win through argument and example. That was his mistake. One has only to examine what the Christians believe to realize that reason was not their strong point.”

Julian’s Downfall

The magician Maximus told Julian that he had spoken to Cybele, the Great Mother, who told him that “One who is now with us shall be with him until he reaches the end of the earth and finishes the work which that spirit began, for our glory….Alexander! You are to finish his work…[In Persia] and India and all that lies to the farthest east…You are Alexander.” Priscus stated if he had known the madness that Maximus was whispering in Julian’s ears then he would have loudly objected, but Julian kept this close to his chest.

Meanwhile Julian sent Oribasius to Delphi to consult the Oracle, which was in a very sad state. “The works of art which had one decorated the numerous shrines are all gone. Constantine alone stole 2700 statues. There is no sight quite so forlorn as acres of empty pedestals. The town was deserted except for a few tattered Cynics.” The Oracle was still functional but was very old with no replacement in sight. After performing the ritual, the Oracle said, “Tell the King: on earth has fallen the glorious dwelling, and the water-springs that spoke are still. Nothing is left the god, no roof, no shelter, and in his hand the prophet laurel flowers no more.” A terrible prediction that Julian would fail in his quest.

Priscus thought the Oracle was in the pay of the Christians knowing what importance Julian set by oracles, and that if the priestess was genuine she would have done everything possible to see that Delphi was restored. But the Oracle turned out to be correct…the Hierophant of Greece, too, who hinted that Julian would fail.

War with Persia

Julian decided on war with Persia. He traveled to Antioch as he was gathering his army and sacrificed at the temple of Zeus; he had performed the ritual slaughter of the bull “ten thousand times” before and there was little he did not know about auguries. But it was not what he wanted to see: the bull stumbled on the way to the alter, which was a bad omen. Then Julian killed the bull and took out the liver for examination:

The omen was appalling. Parts of the liver were dry with disease. I examined it carefully. In the “house of war” and in the “house of love” death was the omen. I did not dare look at Maximus. But I knew he had seen what I had seen. Entirely by rote, I continued the ceremony, held the sacrifice aloft to Zeus, studied the entrails with Maximus, repeated the old formulas. Then I went inside to complete the ceremonies.

To my horror the temple was crowded with sightseers; worse, they applauded as I entered. I stopped dead in my tracks at this impiety and said, “This is a temple not a theatre!” I had now made a complete hash out of the ceremony. If even one word is misplaced in a prayer, the entire ritual must begin again from the beginning. By speaking to the crowd, I had broken the chain that links the Pontifex Maximus with the gods. Cursing under my breath, I gave orders to clear the temple, and to begin again. The second bull - undrugged - tried to bolt just as I raised the knife, again the worst of omens.”

Julian ordered the Jewish temple at Jerusalem rebuilt, because “the Nazarene predicted that the temple of the Jews would be forever destroyed…if I rebuild it, the Nazarene will be proved a false prophet.” The rebuild started but the Christians immediately sabotaged it; Julian planned to restart work but was not able to do so before he died. Julian ordered the bones of the Christian Babylas removed from its shrine thinking it polluted the land of sacred Apollo; then temple of Apollo was burned to the ground in response, a sacrilege and a direct affront to his sovereignty.

A famine struck the land, and Julian responded to the stress by going mad with animal sacrifice:

“On one day at Daphne, he sacrificed a thousand white birds, at heaven knows what expense! Then a hundred bulls were sacrificed to Zeus. Later, four hundred cows to Cybele. That was a particularly scandalous occasion….everyone was shocked at the ritual scourging of a hundred youths by the priestesses….the ultimate rites were a confused obscenity. But Julian grimly persisted, on the ground that no matter how alarming some of these rites may appear to us, each is part of our race’s constant attempt to placate the gods. Every ancient ceremony has its own inner logic, and efficacy. The only fault I find with Julian is that he was in too great a hurry. He wanted everything restored at once. We were to return to the age of Augustus in a matter of months. Given years, I am sure he could have re-established the old religions.”

According to Priscus, “I am sure that if the gods (who probably don’t exist) really wanted to speak to us, they could find a better messenger than the liver of a bull or the collapse of an old priest during a ceremony. But Julian was an absolute madman on this subject.”

Julian received a vision that his life was in danger of a violent end, and there was public rumors that Julian’s days were numbered due to the famine and his religious beliefs. Ten Christians were arrested for plotting Julian’s murder (which was discovered only one day before they were going to kill him) and were executed. Then there was an earthquake at Nicomedia, which Julian read as a mixed omen, and the Sibylline books had a clear message for Julian: do not go beyond the boundaries of the empire this year.

Libanius had good advice for Julian: “I only wish that you would put off going [to war] until next year. You have set in motion a hundred reforms. Now you must see to it that they take effect. Otherwise, the Galileans will undo everything the moment you are out of sight. You cannot control them from the field or even from the ruins of Ctesiphon.” Julian acknowledged the advise but thought that he would be able to push through better reforms if he had the glory from a Persian victory; he was obsessed with Maximus’s prediction that Julian would be greater than Alexander.

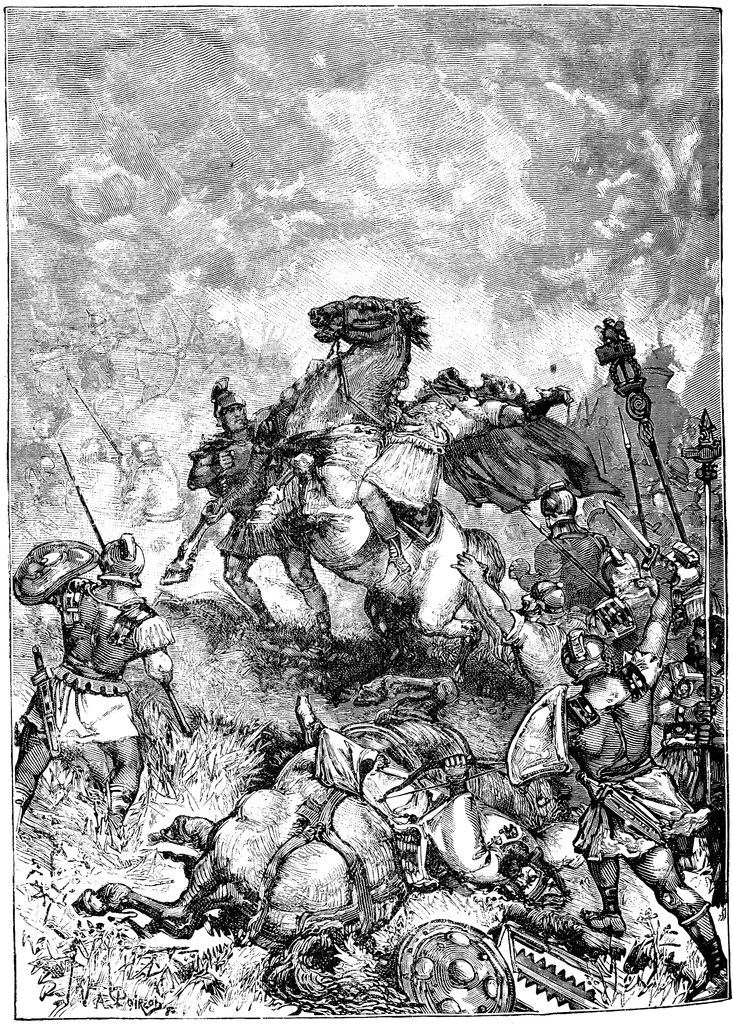

Julian went to war against the Persian King Sapor. Of his soldiers half were loyal Gallic Hellenists and half were potentially disloyal Christians. His strategy was brilliant and he took city after city, town after town, then defeated Sapor at the gates of the Persian capital, but his general (who was Christian) did not pursue the fleeing Persian troops into the open city. Sapor proposed a generous peace on favorable terms to Rome, but Julian did not accept it because of his madness of Alexanderian glory swimming in his head. Instead, he turned it down quietly (he did not tell his troops about the offer, who would have rebelled if they had known) and then in complete madness burned his ships so his troops would have no recourse other than continue to fight.

Seeing this madness, Sapor responded by setting fire to all farmland in all directions, which deprived Julian’s troops of food to forage. Then reinforcements to Julian did not arrive as expected (because they had been bought off by the Persians). Julian did not have siege engines to take the capital, so he was forced to retreat in disgrace.

On the route back Julian was killed, likely by one of his Christian soldiers. Maximus said the locals called the place where Julian fell Phrygia, fulfilling the prophecy about where he would fall. The extent to which his statement was true is unknown.

There had been repeated rumors of attempts on Julian’s life during the campaign, and he was ambushed by Persians at one point early on in a manner where it looked like they knew in advance he would be there. Julian’s murder during the Roman retreat was made to look like a death caused by the pursuing Persians because of fear of retribution by Julian’s loyal Gallic troops; no Persian ever claimed the bounty on Julian’s head, and Julian was killed by a Roman spear.

Julian had experienced signs that disaster was coming; inspection of the liver of another bull he sacrificed indicated disaster. Julian threw down the sacrificial knife in response and shouted to the sky in frustration, “Never again will I sacrifice to you!” The omens continued to be bad and the auguries confused. Then the gods were silent. “I prayed more than an hour to Helios. I looked straight at him until I was blind. Nothing. I have offended. But how? I cannot believe that my anger at the war god would turn all heaven against me. Who else will do their work?” Julian had a dream that the Spirit of Rome had deserted him, and when he woke up he saw a star fall in the west, a sign of a falling Emperor.

In Vidal’s novel Julian’s assistant broke the straps of Julian’s armor (Julian had died without wearing any, responding to a sudden Persian attack) and admitted to murdering Julian. This former assistant, Callistus, later become quite rich, rewarded by the other Christian conspirators for his deed. Bizarrely, Callistus had written a very affectionate “Ode to Julian” after Julian’s death. He was asked, “How could you write such an affectionate work about the man you murdered?” Callistus was perfect in his astonishment. “But I admired him tremendously! He was always kind to me. Every word I wrote about him was from the heart. After all, I am a good Christian, or try to be. Every day I pray for his soul!”

Julian in Context

Future Emperors were all neutral or pro-Christian, and Julian’s death spelled the end of attempts to revive Hellenism.

Less than fifty years after Constantine the death penalty was announced for any who dared to sacrifice. In AD 399 the Christian emperor Theodosius announced that “if there should be any temples in the country districts, they shall be torn down without disturbance or tumult. For when they are torn down and removed, the material basis for all superstition will be destroyed.”2 In AD 423, the Christian government announced that any Hellenists who still survived were to be suppressed. Though, it added confidently and ominously: “We now believe that there are none.”3 Damascius, who was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school, fled to Persia with seven followers under fear of death from the Christians, but life there was unbearable and he and his followers eventually returned where they faded into obscurity. For more information tracing the Christian destruction of the Hellenist world post-Constantine, see here.

states, "What God is going to help people like this? I like the old adage, “God helps those who help themselves.” You have to prove your worth to The Gods. Make agreements with them. Show your superiority and why you should be loved by The Gods." Yet Julian did all of this; he was fanatical in his devotion to them, he sacrificed so much to them, he reopened their temples, he read all the signs, and while the Gods protected him from Constantius and lifted him up to Emperor, they promptly abandoned him within a couple years and he was assassinated likely by a Christian soldier. If the Gods were real and had power, why would they abandon their most ardent follower in the last chance they had to remain relevant for thousands of years? The well-known fickleness of bickering Gods doesn’t explain it.Ultimately Julian came too late -- the cult of Christianity had metastasized by the time of his reign and he was always likely going to fail, with or without the help from the Gods. It's an analysis of societal trends, not appeals to Gods that resulted in Christianity's victory. Christianity had certain memetic improvements regarding centralization and almsgiving, as well as its Heaven-vs-Hell carrot-and-stick that Hellenism couldn’t compete with as a motivating factor (everyone went to Hades) that gave it massive advantages over Hellenism and which is why Julian tried to copy them. As Prohaeresius said, perhaps if Julian had come a couple decades earlier before the trends were so firmly established he could have won. After all, a population naturally follow its leaders (as

argues) which is why Constantine had so much success in spreading Christianity in the first place.But that also raises questions about the woke religion today and how metastasized it is. Trump couldn't even put a small dent in the woke religion. Personally I think it's likely too late and the end result of current trends is probably wokeness destroying western civilization and resulting in white genocide, followed by the potential total collapse of humanity itself. Regardless, one should try to do what one can to avoid this fate.

Thanks for reading.

Tom Holland, Dominion, 141:

Behind the selfless ascetics of Julian’s fantasies there lurked an altogether less sober reality: priests whose enthusiasms had run not to charity, but to dancing, and cross-dressing, and self-castration. The gods cared nothing for the poor. To think otherwise was ‘airhead talk’. When Julian, writing to the high priest of Galatia, quoted Homer on the laws of hospitality, and how even beggars might appeal to them, he was merely drawing attention to the scale of his delusion. The heroes of the Iliad, favourites of the gods, golden and predatory, had scorned the weak and downtrodden. So too, for all the honour that Julian paid them, had philosophers. The starving deserved no sympathy. Beggars were best rounded up and deported. Pity risked undermining a wise man’s self-control. Only fellow citizens of good character who, through no fault of their own, had fallen on evil days might conceivably merit assistance. Certainly, there was little in the character of the gods whom Julian so adored, or in the teachings of the philosophers whom he so admired, to justify any assumption that the poor, just by virtue of their poverty, had a right to aid. The young emperor, sincere though he was in his hatred of ‘Galilean’ teachings, and in regretting their impact upon all that he held most dear, was blind to the irony of his plan for combating them: that it was itself irredeemably Christian.

‘How apparent to everyone it is, and how shameful, that our own people lack support from us, when no Jew ever has to beg, and the impious Galileans support not only their own poor, but ours as well.’ Julian could not but be painfully aware of this. The roots of Christian charity ran deep. The apostles, obedient to Jewish tradition as well as to the teachings of their master, had laid it as a solemn charge upon new churches always ‘to remember the poor’. Generation after generation, Christians had held true to this injunction. Every week, in churches across the Roman world, collections for orphans and widows, for the imprisoned, and the shipwrecked, and the sick had been raised. Over time, as congregations swelled, and ever more of the wealthy were brought to baptism, the funds available for poor relief had grown as well. Entire systems of social security had begun to emerge. Elaborate and well-organised, these had progressively embedded themselves within the great cities of the Mediterranean. Constantine, by recruiting bishops to his purposes, had also recruited the networks of charity of which they served as the principal patrons. Julian, clear-sighted in his loathing of the Galileans, understood this very well. Trains of clients, in the Roman world, had always been an index of power – and bishops, by that measure, were grown very powerful indeed. The wealthy, men who in previous generations might have boosted their status by endowing their cities with theatres, or temples, or bath-houses, had begun to find in the Church a new vent for their ambitions. This was why Julian, in a quixotic attempt to endow the worship of the ancient gods with a similar appeal, had installed a high priest over Galatia, and urged his subordinates to practise poor relief. Christians did not merely inspire in Julian a profound contempt; they filled him with envy as well.

Nixey, 119.

Nixey, 86.

Hard disagree with your last paragraph. Wokism is metastasized, but it is an exterminationist religion far more extreme than Christianity. Christianity is universalist in its actual form: it destroys all other religions but does not target people for their race. Wokism, on the other hand, demands Whites be completely exterminated. They give Whites no way out except to crush them, and more and more Whites are waking up to this fact. The Rhodesians held off against overwhelming odds, it was only the enmity of the other White nations that lost them the Bush War. Even outnumbered, Whites will put up an enormous fight when their backs are put against the wall and will probably win.

Fascinating read. Thank you.