Jung’s Answer to Job: A Psychological Redemption of God?

The Book of Job as a Cosmic Therapy Session

Jung’s Answer to Job presents a radical reinterpretation of the Book of Job, suggesting that God is not omniscient in the way traditional theology assumes but rather an unconscious being who evolves through human self-awareness. Jung argues that Job’s suffering forces God to confront his own moral failings, ultimately leading to the incarnation of Christ as an attempt to redeem Himself rather than humanity. While Jung’s theory provides an intriguing psychological framework for understanding religious evolution, it also raises major philosophical and theological issues, particularly regarding divine omnipotence and the nature of evil. The post explores these ideas, comparing Jung’s interpretation to gnostic and exoteric Christian perspectives while questioning whether his approach truly resolves the problem of suffering or merely reframes it.

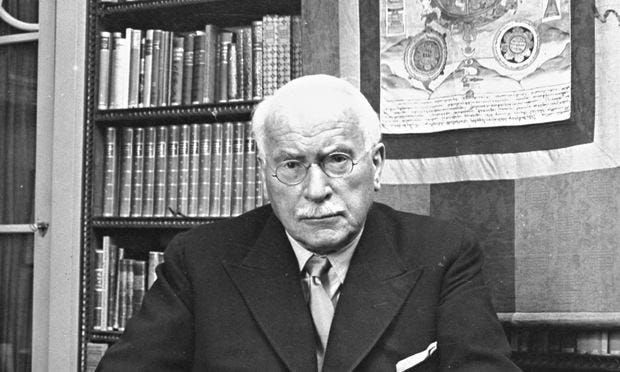

The first Jung book I read a couple years ago was his Answer to Job (1952), a stream-of-consciousness work he wrote feverishly during an illness. The moment he completed it his symptoms vanished. In hindsight this book was not a great place to start my exploration of his oeuvre; it was dense and difficult to follow without the knowledge of his more introductory works. I had anticipated a gnostic interpretation of Job given Jung's reputed affinity for gnostic themes, but instead he sought to synthesize the God of both the Old and New Testaments through the lens of Jungian psychology. In Answer to Job classical Christian doctrine is upended: Jung posits that the purpose of Christ’s incarnation was not to redeem humanity from sin but rather to redeem God for his transgressions against Job.

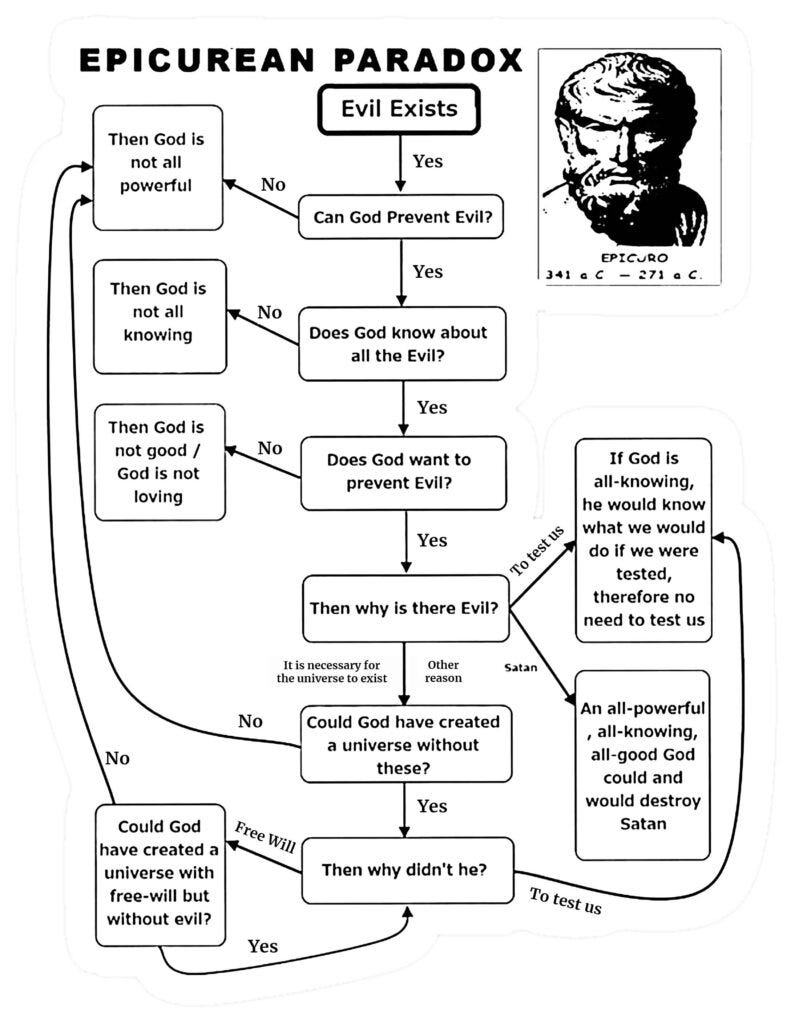

I think the attempt doesn’t quite work, but it’s worth covering because it is an interesting alternative to both exoteric Christian approach to the problem of evil and the traditional gnostic interpretation.1 For reference, the problem of evil is well encapsulated by the Epicurean paradox, flowcharted in an easy-to-understand manner as follows:

Just like I tried to steel-man my argument about the central bank owners by addressing conflicting alternatives here and here, by addressing competing theories to the gnostic perspective my hope is to steel-man that theory as well (unless it persuades me to change my mind).

This wasn’t something I planned intentionally. Why did I begin my exploration of Jung with Answer to Job? The question is a bit backward: Job and Ecclesiastes are my two favorite books of the Bible and I wanted to dive deeper into them. I’m drawn to Job because it grapples with the problem of evil and to Ecclesiastes because of its philosophical pessimism, arguing that everything humans do is fleeting, destined for dust, and based on “vanity.” I might discuss Ecclesiastes in a future post, though I touched on it briefly in my previous post about philosophical pessimism. In any case, I decided to write a post about Job and discovered that Jung had written an analysis of it.

The story of the Book of Job

Most of you already know the story of Job (written sometime between 600-400 BC), but for those who don’t the story is as follows. Job is the most righteous man in the land of Uz, and he is also successful and has a wonderful life and family. The devil tells God Job is only righteous and loves God because of the things he has, and they make a bet that if these things are taken away job will curse God for his plight. God agrees and lets Satan kill Job’s children, ruin his livestock and health. Quite a few of the commandments that God had given to the Jewish people were broken by God here. Job is perplexed and repeatedly prays to God asking why all this is happening to him, but in his torment he does not become unrighteous - he curses the day he was born but does not curse God. Three friends visit Job and argue that he must have sinned to cause such misfortune, but Job rebukes them.

Having finally had enough of Job’s prayers, a wrathful God appears in a whirlwind before him and demands to know why Job dares to question His actions. God offers no explanations for His deeds but instead rages about His immense power and Job’s insignificance. He lists the marvels of creation, highlighting the wonders of the earth, the mysteries that Job can never hope to understand, and the monstrous forces at work - like Behemoth and Leviathan - that Job has no control over. Terrified, Job shrinks in fear and apologizes, much like someone would if confronted by a menacing bully.

Satisfied that Job no longer dares to question His actions, God restores Job’s family, health, career, and reputation. Satan faces no punishment for initiating the wager, and the story leaves unaddressed its central issue: God’s all-knowing, omnipotent nature, which should have meant He knew Job’s heart and could foresee the outcome of the bet without being manipulated by the devil. And with that, the story ends.

It’s a compelling narrative that vividly portrays the God of the Old Testament as flawed - haughty, petty, capricious, unjust, and vulnerable to manipulation by Satan, revealing a deep lack of self-awareness. The story was likely included as a lesson to accept God’s judgment with humility and grace (a point emphasized by Jungian therapist James Hollis2). However, from a modern perspective the takeaway is vastly different: God is to be feared not because humanity behaves unjustly, but because God himself acts as an imperfect, capricious bully, lacking self-understanding.

The gnostic poet and painter William Blake has a series of paintings inspired by the story of Job, which you can see here.

takes his inspiration from this story. The binding of Isaac by Abraham is another story that portrays God in a very poor light, as explains here.Jung’s take

Jung wrote Answer to Job in 1952 in one furious burst of energy when he was seventy-five years old while he was plagued by an illness. Once finished he felt well again. Unlike his other books which were apparently much more measured, Jung intended this book to be a subjective rant, an approach I can appreciate. He knew it would be very controversial so he pared the language and tone back from its initial rough draft, and he was hesitant about publishing it:

“The many questions from the public and from patients had made me feel that I must express myself more clearly about the religious problems of modern man. For years I hesitated to do so, because I was fully aware of the storm I would be unleashing. But at last I could not help being gripped by the problem, in all its urgency and difficulty, and I found myself compelled to give an answer. I did so in a form in which the problem had presented itself to me, that is, as an experience charged with emotion.”

Jung felt that what he wrote about in this book was the unfoldment of “the divine consciousness in which I participate, like it or not.”

When he finally published the book it aroused a lot of controversy; some loved it, some hated it, and he lost friends over it. Still, he was extremely proud of it. Many consider Answer to Job to be his most important work. Jung said that if he could he would go back and re-write all of his books except for the Answer to Job. This was likely hyperbole to upset his detractors.

Jung’s interpretation was grounded in psychology, not religion. For his purposes, whether the Bible is literally true is simply irrelevant. The Bible deals with miracles that are contrary to the laws of nature, otherwise they would be subject to regular studies of history and physics. What matters to Jung is whether the Bible resonates with man on a psychological basis, both consciously and unconsciously. To him specific religions and ideas caught on so strongly in society because they spoke psychological truths to man, it nourished him and gave him a sense of peace in a crazy world, regardless of whether they were literally true. However, just as man over time evolved to become more sophisticated based on experience and societal, cultural and technological changes, man’s conception of God (the “god-image”) evolved too, either because God actually changed or man perceived him in a different way due to his own evolving psychology. Jung looked at the tales within the Old and New Testaments as psychologically true, an approach both the religious and irreligious should be able to appreciate. I know I do. This is a great merging of opposing viewpoints into a higher level synthesis, where this coincidentia oppositorum is at the core of spiritual growth.

The Unconscious God

According to Jung, God’s omniscience inherently precludes self-awareness - being omniscient, God has no distinct, focused self to recognize. Being a part of everything, God has no opportunity to distinguish self from non-self which is necessary for consciousness — as such, he is an entirely unconscious being. However, through the thoughts of his creations he can experience what self-awareness is and grow through this process. According to Paul Levy’s analysis,

In this book Jung interprets world history as a dreaming process of a greater being (which we call God), whose origin lies outside of time and yet is manifesting—and revealing itself—in, through and over time. Jung writes, “the imago Dei (God-Image) pervades the whole human sphere and makes mankind its involuntary exponent”. In other words, an atemporal, eternal process is manifesting itself historically in, through and over linear time, which it did not only two thousand years ago, but, as Jung realized, events in our world today are the current reiteration—and revelation—of the same deeper archetypal process of the incarnation of God in human form. This time, however, instead of appearing in one man—in projected form outside of us—this is a process in which all of humanity has gotten drafted into participating….

As Jung wrote in Answer to Job, due to our littleness and extreme vulnerability, there is one thing that humanity possesses that God, because of his omnipotence, doesn’t possess - the need for self-reflection. As Jung poetically expresses it, in the human act of self-reflection, God becomes motivated to step off his throne, so to speak, and incarnate through humanity in order to obtain the uniquely precious jewel which humanity possesses via our self-reflection. In other words, the act of deepening our realization of the Self has an effect upon the Self that we are realizing.

Our reflecting upon ourselves is the very role that we are meant to play in the divine drama of incarnation. Self-reflection is the best service we can offer to God—not to mention ourselves and the world. It should get our highest attention, as Jung elucidated in Answer to Job, that evil—personified in the story of Job by Satan—is the very catalyst for us to reflect upon ourselves. This brings up the question of who Satan works for—is he an emissary of the darker forces, or is he a secret agent for the light? The answer to this question depends upon whether we recognize what is being revealed by—and through—the darkness.

Jung expanded on this idea in his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections, where he wrote:

The ritual acts of man are an answer and reaction to the action of God upon man; and perhaps they are not only that but are also intended to be “activating,” a form of magic coercion. That mans feels capable of formulating valid replies to the overpowering influence of God, and that he can render back something which is essential even to God, induces pride, for it raises the human individual to the dignity of a metaphysical factor.

Or see Jungian psychologist Edward Edinger’s five minute explanation reflecting the same idea:

As an aside, this take kind of reminds me of the great Ori villains in Stargate: SG1, who live in a different dimension but feed off the worship and attention of their followers.

Flaws with Jung’s theory

I have mixed feelings about Jung’s explanation. His attempt seems flawed because it makes major assumptions about how consciousness applies to God. See this June 10, 1991 Time magazine article by Lance Morrow, who states that one could agree with any two of these three propositions, but not all three: (1) God is all-powerful. (2) God is all-good. (3) Terrible things happen. You can believe that there is an all-powerful God who allows terrible things to happen, but this God could not be all-good. On the other hand, there might be an all-good God who lets terrible things happen because he does not have the power to stop them; thus he is not all-powerful. At the beginning of his Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas admitted that the existence of evil is the best argument against the existence of God.

Jung assumes that while God is omnipotent he is not truly omniscient - or, at least, that he is not in tune with his own omniscient aspect. In the story of Job Yahweh is not split but is a totality of inner opposites, and this Jung identifies as the coincidentia oppositorium, the conjunction of opposites. A God outside of space and time but infused in every aspect of existence (panentheism) would not necessarily have a need to grow consciously within space and time as it is infinite outside of it, so it seems like Jung is taking a leap in logic. On the other hand, the exoteric Christian idea that God is all light and all good and everything that’s evil is the absence of light/goodness (the privatio boni theory of evil) I find to be limiting of God’s abilities, as does Jung — He is everything, and that ultimately includes the evil side as well. Compare this with Plato, who inspired exoteric Christianity with his form of the good, which notably excludes the form of the bad. Jung saw this evil side of God as the missing fourth element of the Trinity, which he believed should be supplanted by a Quaternity. Victor White, an English Dominican priest who Jung conversed with, accused Jung of being a Manichean dualist. Seeing God as containing evil is not a pleasant perspective, though: Marie-Louise von Franz reports that when Jung was asked how he could live with the knowledge he had recorded in Answer to Job, he replied “I live in my deepest hell, and from there I cannot fall any further.”3

To Jung, the story of Job is a highly embarrassing one for God. It paints God as an un-self aware bully. As the story took hold in society, it stimulated something in God to grow and respond to the accusations that he was unjust: it signaled the return of Sophia, the goddess of wisdom, to assist God in this process. This culminated in God deciding to become man through Christ in order to experience humanity’s suffering himself. In other words, the collective response to the story of Job forced God into growing his consciousness. His desire to become man was signaled in the Book of Enoch and also the Book of Daniel. The major plus from a perspective like this is it assigns to man a role of cosmic importance: to stimulate God to develop his consciousness in order to evolve alongside mankind. If embraced by society at large, this perspective could restore humanity’s divine significance, providing meaning to our existence and perspectives, effectively banishing nihilism. And that would be incredibly powerful. This is apparently similar to the Kabbalistic view of man’s role to benefit God as represented in the Zohar.4

But what kind of God needs to atone for the sins of man (or his own) by manifesting as human in order to form a blood sacrifice? What kind of father is he who is appeased by murdering his own son? After Christ’s return the Apocalypse of John signals that God’s unconscious will return in the future — but in the form of the anti-Christ.

Ultimately, the idea of God expanding his consciousness while seemingly setting aside his omnipotence—if I’m understanding Jung’s framework correctly—feels forced and limited to me. There’s a lot of mental acrobatics involved, even though Jung’s perspective could restore humanity’s cosmic significance and push back against nihilism, which would certainly have value. It seems simpler to attribute the flawed and painful material world - full of imperfections, evil, suffering, and sociopathic dominance - to the creation and management of an imperfect, blundering Demiurge, while the God of light and justice exists beyond this realm. This approach offers a more straightforward solution to the problem of Job. It also raises the question of whether the God of light is superior and more powerful than the Demiurge, or if they are equally strong, as in Zoroastrianism (or maybe the Demiurge is more powerful?). But that’s a whole separate issue. Perhaps, though, this approach is just shifting the problem and the Demiurge is merely an inferior aspect of the Divine Whole, bringing us back to Jung’s view. Scholarly reactions to Jung’s ideas are mixed, but they continue to spark serious debate and discussion.

I’d like to end with gnostic Bishop Stephan Hoeller about the four steps toward actualizing consciousness, discussed previously here:

The first step in the actualization of the myth of consciousness is that we permit the destruction of the universe in which we have existed. More often than not this involves primarily a “relativation” of our “personal” reality. The word ‘personal” means that just as our perception of reality is our own, so too its altering must be confined to our own selves. “Relativation” implies that this process is not an extinction of old values, but rather a process which renders relative the concepts and values which we previously considered to be absolute. Specific values increase while general values decrease. Concrete realities become more important than abstract principles. While this may seem a terrible thing to say, as a result of this process we become in a certain sense unprincipled. What actually happens is that when reality takes over abstractions are reduced to their proper size. When we enter the practical realm of the myth of consciousness we enter the fluid, mercurial realm of psychic reality where all rules engraved in stone are inappropriate. Attachment to rigidly held abstractions, to theories and doctrines of any variety diminishes and eventually vanishes. What remains is the living reality of the deeper psyche operating from its own vision and guidance….

The second step in the enactment of the myth is the entry of the psyche into the process of creative conflict. This means that we must leave behind our attachment to the current overvaluation of tranqulity or lack of conflict and also to the overvaluation of health, wealth and power. One of the ways that this change may be approached is by contrasting the conditions of a static state with those of a process. We must recognize that tranquility, peace, health, wealth and power are all descriptions of states or conditions. They are not processes. Consciousness, on the other hand, is a process, not a state of being. This brings up the issue of commitment. To what is an individual committed in an active pursuit of the myth of consciousness? The commitment must always be to the process and never to the outcome. Persons, symbols, ideas and ideals can all find their proper places within the process but the process itself must be regarded as primary, other goals as secondary….The sense of the drama of the soul is growth through conflict. The creation and enlargement of consciousness cannot take place without the creative alchemy of conflict…in the conflict we may need to experience defeat and lamentation before the archetypally facilitated resolution can occur. If the process is interrupted when it becomes dark and painful the chances are lessened that the resolution we desire will come about.

Thus by the conflict of will and counterwill, of yes and no, affirmation and negation, and in the ultimate resolution of these conflicts brought about by the wisdom of the archetypal psyche, consciousness is born and expands. Moral opposites are very much part of this process so that the psyche is forced to make choices that are not dictated by external commandment but by individual, conscious insight. The objective of this process is not moral goodness but conscious wholeness of the psyche.

At this point, we come to another predicament. Since in the course of the pursuit of the myth of consciousness we cannot follow the accustomed moral impulse to espouse one opposite as against another (not even good against evil), we no longer have the luxury of feeling righteous. We are, in fact, no longer “good” men and women….Instead, we must become alchemical vessels in which light and darkness, good and evil, male and female struggle, embrace, commingle, fuse, die, and are born. All our cherished ethical beliefs - monotheism, the belief of Jews and Calvinists that they are chosen people, predestined for righteousness - vanish before our eyes. Our moral superiority also evaporates. Not only are we no longer able to condemn others we may consider unrighteous but we are also not able to condemn that side of ourselves that we have been taught to despise and abominate….

The third step in the actualization of the myth is the conjuction of the opposites which follows their conflictual interaction. This step represents the best mechanism for the generation of consciousness. When the union of opposites occurs consciousness is born…leisure and work, altruism and self-love, youthful energy and mature wisdom, idealistic self-sacrifice and common sense frequently wrestle and conjoin within us, thus bringing us to more highly developed states of consciousness….

The fourth and last step of the myth is…”the transformation of God”…unlike the gnostics who remained silent about the possibility that the Demiurge could be redeemed, Jung time and again affirmed that the Creator-God could be redeemed by becoming conscious, and that this process could be facilitated by humanity. While mainstream Christianity holds that God redeems human beings, Jung held that humans could redeem God. The question is how can this redemption be accomplished?

God’s unconsciousness, Jung said, has one primary manifestation - the loss of its feminine side. In Answer to Job, Jung wrote that the Creator-God once had a feminine side who was his sister, consort and possibly his mother all at once and that her name is Sophia, which means “wisdom".” By losing contact with Sophia God became unwise or, in psychological terms, unconscious. Thus it is evident that the Creator-God’s way to consciousness leads to the feminine which he needs to recognize and to rehabilitate, and with which he must achieve union….

The significant conclusion that needs to be drawn for our purposes is that, while the wholeness that needs to be brought to the Creator requires rescuing and elevating the Divine Feminine, this task need not be wedded to historical and anthropological theories which are highly speculative. Thus, bringing wholeness to the lonely, irascible and in part unconscious male Creator-God is not a political task but a psychological one and even a spiritual one. The problem with this task, as Jung very bluntly stated, is that “America is extroverted as hell.”…Money, prestige and power are goals that appeal strongly to the extroverted psyche; psychological transformation does not….

Thus we must recognize that the issue of God versus Goddess is not about class warfare or political power, but rather about psychological and ultimately metaphysical wholeness. Those people who recognize this clearly and are willing to act upon it will be the true heroes of consciousness. They will help to restore wholeness and create consciousness in the souls of men and women and, beyond that, in the subtle, metaphysical dimensions of gods and goddesses. To quote Edinger…”As it gradually dawns on people, one by one, that the transformation of God is not an interesting idea but is a living reality, it may begin to function as a new myth. Whoever recognizes this myth as his own personal reality will put his life in the service of this process.”

Thanks for reading.

PS: While I have not enabled paid subscriptions at this time, I am going to try out crypto if you found my work helpful and would like to donate. Posts are and will remain free. This is an experiment and is subject to further changes:

Bitcoin: bc1qh6cdaagqwcmp7ctqt9gdj6y6xjr88a7pz7fgpg

Ethereum: 0x30DB893613D032cdcE3B4F6De86aF921A236a7C3

Monero: 43CX9B3nfmJcmrD624pTq86gNRFeEk2eMMWjWtMy59afX8Szrxt88VkXRw6ez3LKWXcLtZxWjGgrk9Kecv9xvqsvGJcGrVa

The gnostic take is that the God of the Old and New Testament are simply different Gods — where the God of the Old Testament is the Demiurge, the malevolent but bumbling creator and maintainer of material reality, while the God of the New Testament, the one of love and pacifism, is entirely a spiritual God who is far removed from the material plane.

In Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life, Hollis writes: “When God does appear to [Job], as a voice out of a metaphoric whirlwind, He tells Job that He does not have to answer to Job’s idea of the agreement between them. It seems that the God of the universe will be bound by no contract, at least not one struck by humans. Job experiences a revelation, a transformation of perspective, and declares that his widely proclaimed piety was based on a hubristic assumption that his compliant behavior compelled God to treat him well. Job realizes that there is no deal, that such a deal is a presumption of the ego in service to its now familiar agenda, which promotes its own security, satiety, and continuity….But such deals with the universe are our fantasy alone, and have little to no bearing on reality….Sooner our later, life brings each of us not only disappointment, but something worse, a deep disillusionment regarding the “contract” that we tacitly presumed and served to the best of our abilities….As deep as the suffering may prove in our outer world, this other spiritual suffering, this loss of one’s fundamental understanding of the world and how it works shakes the foundations of beliefs even more…..Such a crisis is an existential wounding and a spiritual wounding as well….This betrayal by the other - by God, by our lover, by our friend, by the corporation - is a betrayal of our hope that the world might be manageable and predictable…As the child once fantasized that heroism could manage to do it all, so the person in the second half of life is obliged to come to a more sober wisdom based on a humbled sense of personal limitations and the inscrutability of the world….We learn that life is much riskier, more powerful, more mysterious than we had ever thought possible. While we are rendered more uncomfortable by this discovery, it is a humbling that deepens spiritual possibility.”

The Zohar’s theurgical approach argues that not only does God redeem man but man redeems God offers parallels to Carl Jung’s work. Both the Zohar's theurgical approach and Jung's psychological framework suggest that humanity's actions, whether through spiritual practice or psychological growth, play a role in an unfolding divine process. In the Zohar this involves the human soul repairing the divine cosmos through its actions, essentially "redeeming" God from the hidden or fragmented state of creation (although “tikkun olam” in the way it is commonly used seems, to a significant extent, to be both destructive to mainstream society and to advance elite interests). In Jungian terms, this could be seen as making the unconscious aspects of God (or the divine archetypes) conscious, integrating hidden aspects of the divine and allowing for a more complete, conscious relationship with the divine.

Why do we need the idea of some god that is humanized?

Same reason why we humanize our pets....a stupid human trick to pretend like we understand.

With language, our brains were nudged to tune into a common prediction instead of personal prediction. When one relies on others to know what is real or not, they aren't using their own senses to confirm it, whether by thought or experience. Language replaced the need to experience something to consider it real.

Here's a documentary of the Piraha Amazonian tribe that were being told about Jesus. Notice how they do not take the past as fact, just because it was in the Bible, etc.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=BNajfMZGnuo

https://robc137.substack.com/p/alphabet-vs-the-goddess

Weird! It's like we are switching roles.

I began the Children of Job substack with an exploration of the book of Job and the Tanakh, the Old Testament, with particular reference to Jack Miles’ God (which I recommend). His interpretation of the book of Job echoes Carl Jung from fifty years earlier, with Answer to Job, a book I first read in my twenties.

Mission crept over the ensuing months, until I wound up writing a lot more about standard sociocultural engineering operating procedures, the Jew Question, World War 2, and even taking an unprecedented (non-voluntary) dive into Trumponomics. Early on, I came on yr site, and yr writing on international bankers had an influence on my understanding of the JQ, and we argued (a bit) over DJT & movies.

Now it's a few days before Lent, during which I plan to take an Internet sabbatical, and I have six weeks’ worth of posts scheduled to air in my absence. None of them were about Job (until now), but I have been wondering if, when (or if?) I return, I will finally get back to the God stuff.

Then, out of the blue, you write a piece about the book of Job. Evidently, Substack abhors a vacuum!

Reading yr piece I felt my response getting longer & longer, the more I read. Now it’s 2,000 words and that means it will be a full article which will get queued up behind all the other posts and won't be online until near the end of Lent (sorry); but it may herald the return to the God-stuff I was hoping for!

Time is not what it seems to be. Watch this space. :)