Philosophical pessimism: A denial of history as progress

Examining a maligned philosophy via Joshua Foa Dienstag's work

This post argues that philosophical pessimism has been widely misunderstood, especially in the west and in the modern era, and that properly understood it provides a counter-balance to the false perspective of history-as-progress which results in continuous disappointment. If you are an optimist by nature, remember Aristotle: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it”.

“There is only one inborn error, and that is the notion that we exist in order to be happy….So long as we persist in this inborn error, and indeed even become confirmed in it through optimistic dogmas, the world seems to us full of contradictions.” - Arthur Schopenhauer

“The future is the only transcendental value for men without God.” - Albert Camus, The Rebel

In a comment to my post “The era of empty, secular mass consumption is over”,

left a comment stating “I think this is a little too pessimistic. Perhaps likely, but better outcomes can't be entirely discounted unless we give up on pursuing them.” I responded, “My disposition is toward pessimism generally because I hate being surprised to the downside. I like to focus on the negative and be pleasantly surprised by the upside if it happens….But we all need hope, life is struggle, and I agree with you that it's better to fight for a better world than simply withdraw.”This response leads to various questions about the nature of pessimism, and this post explores these thoughts. In the modern west, pessimism is seen as an emotional disposition, a derogatory term of abuse against a perspective perceived as repellant, passive, weak, and held by weird, low-status losers. It is seen as an attempt to justify doing nothing, a haven for empty complainers, too scared to go out into the world to try to accomplish something. Contrast this with optimistic perspectives that are seen as rational and productive, who see history-as-progress (“Whig history”), which is ubiquitously accepted in the modern west and which is a secularized version of immanentizing the eschaton. Optimism is the perspective of winners and do-ers, right? But there is a sinister side to optimism, too, which we will discuss. Anyway, pessimism has a less negative connotation in Europe, and a much different and more accepted connotation in earlier eras.

The Neoliberal Feudalism framework sees history pessimistically: not that things will get worse, per se, but rather that human psychology and incentive structures are perennial issues that will not get better, that everything has a trade-off with it and people are inclined to take short-term easy solutions which cause more problems later. History is seen as a series of cons with elites fooling the gullible masses with endless propaganda, no accountability, and with no lessons learned - for all eternity.1 The egalitarian ratchet effect gradually crushes everything that is noble, strong, honorable, robust, involving self-determination and personal excellence (not that being a non-elite in master morality Rome was any better), while humanity reaches its Malthusian limits as it unsustainably consumes the world’s natural resources leaving a trash-heap of rubble and extinction behind. Meanwhile a kind of blind, unthinking centralization process occurs which increasingly removes from humanity its self-sufficiency, privacy and even basic dignity. From this perspective history is seen not as a continuous progress from darkness to light but rather in a much more sinister light. And given that the nature of reality is one of predation - living things can only survive by consuming other living things - the incentive structures look created by a malicious creator-deity, the Demiurge.

As I have mentioned elsewhere, adopting a pessimistic attitude toward the possibility of positive political change has made my political predictive abilities, by and large, much stronger than they were before this shift.

To be clear, this perspective is not meant to cause paralysis or passivity, but rather to set baseline expectations about how we should view the world, to approach events and situations without expectations that they will magically work out for the best. Rather, the range of possibilities is much wider and more flexible than a rigid history-as-progress model suggests. Embraced in this manner, pessimism can lead to increased freedom, unshackled from the Whig model with its expectations of constant progress, leading to vast disappointment when such progress does not materialize.

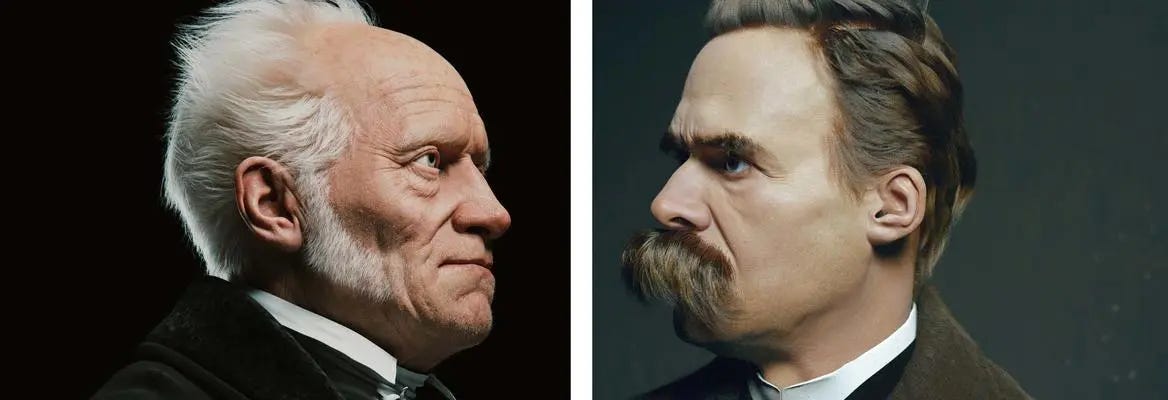

To flesh out my understanding of the intellectual tradition of pessimism, I picked up Joshua Foa Dienstag’s difficult book “Pessimism”. According to Dienstag pessimism has a rich philosophical history, drawing from such figures as Rousseau, Leopardi, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Weber, Unamuno, Ortega y Gasset, Freud, Camus, Adorno, Foucault, and Cioran. A bit ironically, I put off reading it because I didn’t want to get sucked into negativity (ha), but was pleasantly surprised by the power and insight of its articulated core points.

With that said, let’s begin with defining philosophical pessimism.

What is philosophical pessimism?

Pessimists “generally do not set out a scheme of ideal government structure or principles of justice. Theirs is (for the most part) a philosophy of personal conduct, rather than public order. Since such schemes or principles are, to some, the very essence of a political philosophy, this fact, by itself, has been enough to disqualify the pessimists from serious consideration in some quarters.”

The central claims to which all pessimists share to greater or lesser degrees are a series of propositions which, per Dienstag, are as follows:

Time is a burden;

The course of history is in some sense ironic; and

Human existence is absurd.

The reaction to belief in these propositions takes one of two approaches, to various extremes: either (1) ascetic resignation, like Schopenhauer, or (2) those who reject resignation in favor of a more life-affirming ethic of individualism and spontaneity in spite of the horrors of reality, like Nietzsche.

Let’s explore these propositions and then the reactions to pessimism by its adherents.

#1: Time is a burden

Humans are separated from animals by their sense of time-consciousness. Animals live exclusively in the present, while humans have a linear sense of time. According to Nietzsche, animals live “unhistorically” in the sense that they can form no concept of past or future. They “respond to stimuli in the present in a routine and automatic way as their nature dictates but are unable, on the one hand, to form plans or hopes about the future, and on the other, to have regrets or satisfactions about the past….The timelessness of animal existence, whether seen as an Eden or as an infancy, is something we have left behind and can never recover, except perhaps in occasional moments of reverie or transcendence.” Having time-consciousness is a burden because, per Rousseau, consciousness of time means consciousness of death, and he calls this knowledge one of the many “terrors” of consciousness. Freud says “the aim of all life is death.” Per Dienstag,

This sentiment - of the constant presence of death in our lives - is both central to the pessimistic tradition and also central to misunderstandings of it. Critics have often used this sort of material to accuse the pessimist of teaching resignation or nihilism. But this is usually (though not always) a mistake. It is not the pessimists, but their opponents, who draw the conclusion that the acknowledgment of death must lead to inactivity or helplessness. This is hardly ever the conclusion of the pessimists themselves. To say that our lives are always on the way to death is not at all to say that they are pointless, but simply to set out the parameters of possibility for our existence. Pessimism may warn us to acknowledge our limitations - but it does not urge us to collapse in the face of them. Death is merely the ultimate reminder that we do not control the conditions of our existence and are not ever likely to.

Schopenhauer laments “time and that perishability of all things existing in time that time itself brings about…Time is that by virtue of which everything becomes nothingness in our hands and loses all real value”, referring to this phenomenon as the “vanity of existence.” This is emblematic of what Leopardi referred to as the nature of temporal, non-progressive existence: constant change to no particular effect. Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describes life as “futility” akin to “the pursuit of wind” and "Vanity of vanities! All is futile!"

The perishability of all things results in a sense of unreality to life. For Schopenhauer, the implication is that all striving is in some sense futile; whatever goal one achieves will disappear the moment it arrives. We suffer most from the lack of permanence in the people and things we most care about. The more we care, the more we suffer.2 Animals lose whatever it is they possess too, but “only humans feel the pain of that loss since only human consciousness retains a sense of these things as past. Nor is our capacity for hope or anticipation of the future a compensation for this condition. Indeed, it compounds our situation, since most of our hopes are bound to be disappointed, and those that are fulfilled are disfulfilled in the next moment as the objects of our hopes slip into the past.” Time-consciousness, then, results in unhappiness, even though we receive the compensation of consciousness itself - the intellectual ability for higher thought.

#2: The course of history is in some sense ironic

Pessimists do not deny the existence of progress in certain areas, such as technology and science. Instead, “they ask whether these improvements are inseparably related to a greater set of costs that often go unperceived. Or they ask whether these changes have really resulted in a fundamental melioration of the human condition. This often results…in a conception of history as following an ironic path, one that appears, on the surface, to be getting better when in fact it is getting worse (or, on the whole, no better.” Leopardi explains that “if humans were happier as animals than as conscious beings, then as primitive, ignorant conscious beings they remain happier than as more developed and civilized ones. Since the reality of temporal existence is transience, decay and death (point #1), happiness is found in illusion. The piercing of illusion may be counted as a philosophical, and even a moral, advance. But if we knew of the consequences beforehand and cared about our happiness, such insight would not be pursued. The growth of reason, however, once initiated cannot be frozen at any point. Knowledge cannot draw a limit to itself since the knowing mind finds it nearly impossible to value ignorance.” Therefore, “what appears from one perspective to be an advance is, from another, in equal measure, a diminishment. Every step away from our animal condition is a step closer to misery; the path toward enlightenment and the path to hell are one and the same. Nor is this trajectory reversible. Reason, once engaged, has its own logic, and we can no more ignore its conclusions than we can consciously decide to become unconscious.” Rousseau argued that “our souls have become corrupted in proportion as our Sciences and our Arts have advanced toward perfection.” The decline of morality derives directly from mental growth; thus while human reason is “perfected", the species is “deteriorating.” Or per Ecclesiastes, “And I gave my heart to know wisdom, and to know madness and folly: I perceived that this also is vexation of spirit. For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.”

There is another aspect of this too: boredom. If history neither repeats nor improves, most pessimists see life as a kind of earthly purgatory where nothing changes but nothing lasts forever. “Human beings often manage to distract themselves from this underlying reality, but when they do not, or their distractions fail, boredom is the inevitable result….Since boredom springs from this fundamental attribute of self-consciousness, it is effectively the baseline mental condition from which we can only be distracted, either by pain or by relentless activity. The latter does not bring happiness, exactly, but at least it is neither pain nor tedium, the two most common conditions.” This is reminiscent of Kaczynski’s notion of surrogate activities which are used to keep boredom at bay. Schopenhauer connects the prevalence of boredom to the absence of true pleasure in life. Pleasure is only the temporary satisfaction of desire, an absence of pain, and the ease of encountering one form of pain or another - coupled with the human mind's ability to be pained by inconsequential things it desires, and our awareness of impending death - means we get more pain than pleasure:

We are, he argues, compelled by needs which are hard to satisfy. But even when do satisfy them, “their satisfaction achieves nothing but a painless condition in which [man] is only given over to boredom…and that boredom is direct proof that existence is in itself valueless, fore boredom is nothing other than the sensation of the emptiness of existence. For if life…possessed in itself a positive value and real content, there would be no such thing as boredom: mere existence would fulfill and satisfy us. As things are, we take no pleasure in existence except when we are striving after something.”

It is the optimist philosophies who claim that the increase in human mental and technological abilities will inevitably produce a society of happier individuals, but whether this assertion is made in a Platonic form or in an Enlightenment form, it is a false promise, and a promise that creates expectations that lead to disappointment and unhappiness. This is also why Lennon’s pleasant-sounding “Imagine” is the theme of the most bloodthirsty tyrants in history, as it promises a utopian future at the expense of the present with no possibility of fulfillment.

#3: Existence is absurd

Existence is absurd because freedom and happiness are incompatible. We are taught by the false optimism that pervades society to believe that our goals and dreams are achievable, but we are constantly disappointed by their failures:

To the pessimists, human existence is not a riddle waiting to be solved by philosophy; human existence merely is. Freedom and happiness do not exist as the solution to a problem. Rather, starting with Rousseau’s contention that reasoning is against Nature, pessimists have asserted, contra the optimistic Socrates and his descendants, that freedom and happiness are in a fundamental tension with one another as a result of the ontological “divorce” between the time-conscious being full of desires, goals, and memories and the time-bound universe that constantly destroys the objects of its inhabitants’ desires….Socrates had it exactly backwards; it is only release from the burdens of consciousness, which ultimately means time-consciousness, that could purchase our happiness.

The absurdity of existence to the pessimist is contained in the idea that freedom and happiness oppose one another. Schopenhauer writes, “There is only one inborn error, and that is the notion that we exist in order to be happy…everything in life is certainly calculated to bring us back from that original error, and to convince us that the purpose of our existence is not to be happy.” Or as Dienstag argues,

Put another way, we can say that there is a kind of pragmatism buried so deeply in Western philosophy that it is almost impossible to root out. This is the notion that there must be an answer to our fundamental questions, even if we have not found it yet, and that this answer will deliver us from suffering. That is, there must be a way for human beings to live free and happy….It is this widely shared model of a universe predisposed to being subdued by the proper dialectic that pessimism objects to via the language of the “absurd.” Pessimism differs from other modern philosophies, then, not because of a recommendation of lassitude but because of a diagnosis of the human condition that finds no basis for the faith in progressive reason that these varieties of optimism share.

The response to pessimism

There are two general responses to pessimism by its adherents, represented on two poles: advocation of a retreat from life like Rousseau and Schopenhauer, i.e. to live a life of ascetic withdrawal, or alternatively to affirm and embrace life despite living in an absurd world full of pain, without expectation of time-as-progress, which is the approach of writers like Camus, Nietzsche, Unamuno and Leopardi.

For Schopenhauer, the pains of time-consciousness are a just punishment for our evil natures, where he writes:

As a reliable compass for orienting yourself in life nothing is more useful than to accustom yourself to regarding this world as a place of atonement, a sort of penal colony. When you have done this you will order your expectations of life according to the nature of things and no longer regard the calamities, sufferings, torments, and miseries of life as something irregular and not to be expected but will find them entirely in order, well knowing that each of us is here being punished for his existence and each in his own particular way.

With an attitude like this, why didn’t he kill himself? While Schopenhauer and Leopardi have sympathy for those who find the burdens of existence too much, none of the pessimist philosophers recommend suicide and, for the most part, their aim is to find reasons to oppose it. Schopenhauer viewed the world as an illusory representation, that only our will is real and that will is not affected by death, so suicide changes nothing, “it affords no escape.” In fact, Schopenhauer arguably led a life at odds to an extent with his philosophy. Anyway, Schopenhauer’s essays on pessimism are delightful and available online here, and I highly recommend them.

In contrast, Nietzsche, who saw the world just as Schopenhauer did as a place of continuous suffering, took the opposite approach: “You ought to learn the art of this-worldly comfort first; you ought to learn to laugh, my young friends, if you are hell-bent on remaining pessimists. Then perhaps, as laughers, you may someday dispatch all metaphysical comforts to the devil - metaphysics in front”. Nietzsche believed that Schopenhauer’s retreat into asceticism was born from weakness, shirking from accepting life as it is on its own terms. By embracing life as change, the natural result of a temporal existence, per Dienstag, “a pessimist can recognize and delight in the fact that we live in a world of surprises - surprises that can only strike the optimist as accidents and mishaps, disturbing as they do a preordered image of the world’s continuous improvement. This openness to the music of chance lends to the pessimist an equanimity that might strike an outsider as callous. The optimist, on the other hand, must suffer through a life of disappointment, where a chaotic world constantly disturbs the upward path he feels entitled to tread.”

Here is a great article by Dienstag if you want to read more about Schopenhauer and Nietzsche’s alternative responses to pessimism.

Conclusion

The question is ultimately this: what type of relationship do we want to have to the present and future, one of freedom or enslavement? According to Dienstag, “optimism subordinates the present to what is to come and thereby devalues it. Pessimism embodies a free relation to the future. In refraining from hope and prediction we make possible a concern that is not self-abasing and self-pitying. By not holding every moment hostage to its future import, we also make possible a genuinely friendly responsibility to ourselves and to others.”

Personally, I embrace this pessimistic spirit, even though I am myself torn between Schopenhauer and Nietzsche’s position - why strive, when striving will inevitably result in loss and failure? Nietzsche went insane, after all. But then why live if one is not striving for goals and living — a life as an ascetic doesn’t sound very appealing either. And it’s debatable how much Schopenhauer lived his own philosophy! I’ve more or less taken a middle road, trying to survive in the world and build a life while nurturing an increasing understanding that everything is fleeting and there is no expectation that tomorrow will be better, allowing me to set proper expectations for myself that do not result in being regularly surprised.

I hope you found this primer on pessimism helpful, and hopefully this post has a small effect on removing the terrible reputation it has from your mind.

Thanks for reading.

It is much easier to avoid this perspective during times of economic prosperity, and time is indeed cyclical ala Spengler. But we are at the start of a period featuring a massively declining quality of life, so it is a good time to embrace a more pessimistic philosophy. I also generally prefer not to focus on the cyclical nature of civilization because of concern that it could make one too passive (i.e. society is turning to Hell so why bother focusing on it, it’s only natural) while I would rather rage against the dying of the light.

There are a lot of commonalities between Schopenhauer’s thoughts and Buddhism, which he called the “best of all possible religions”. I used to practice Vipassana meditation and kind of miss it; there was no dogma involved which was very refreshing. I even attended one of the ten day retreats. The technique is simple: you spend the first two days focusing your attention only on your breath (in a guided meditation hall for ten hours a day), inward and outward. You come to see how wild and uncontrolled one’s thoughts are; you try to focus on your breath but the mind keeps wandering, like a wild stallion. After two days the mind finally calms down. The rest of the ten days are focused on scanning your body top to bottom, over and over, feeling whatever sensation comes up, good or bad, without reacting to it. Whenever the mind wanders you calmly bring the attention back to the scanning. This results in a deepening sense of calmness of body and soul. I walked out of the retreat with an unsurpassed sense of calmness and well-being (for me), but one is supposed to meditate for a minimum of two hours a day to keep the accrued benefits, and I was not able to do so. Maybe I’ll revisit down the line. The Art of Living by William Hart is a great primer on it.

As a natural pessimist, I am also a relatively content, happy-ish person who strives for a better future (which is always to maximize freedom). I find no contradiction in this. I build things knowing that the great god Entropy shall break them back down to nothing. I enjoy the process of building despite this inherent knowledge. I find so much human striving funny in the most absurd way. Unlike others, I don't believe pessimism keeps me from striving for a better future, I am just not shocked and dismayed when it fails to reach my intent.

Thanks for giving me some academic backstop to my natural impulses.

I wonder how much traditional faith in providence would be considered pessimism now that it’s an accepted norm to place one’s faith in the promises of the state.