The Praetorian Guard: The maker and breaker of emperors

The precursor to the modern-day transnational security elite

This is a post about the Praetorian Guard in Rome and how they became kingmakers, the makers and breakers of emperors. This is important because the modern day Praetorians, the makers and breakers of presidents, the enforcers of globohomo dictates worldwide and the initiators of wars, are the transnational security elite. Therefore to see how the Guard evolved over time, the challenges it faced and how it was eventually disbanded sheds light on our modern kingmaker institutions, the CIA and FBI, which is currently assisting with globohomo tactics to unlawfully imprison Donald Trump, a topic I previously covered last July here.

As I have written about previously in my discussions of Lee Kuan Yew and Pyotr Stolypin, there are two basic forms of governance:

a so-called “democracy” or “republic” which is in actuality an oligarchy (because those who control the propaganda organs control the population), where the top and the bottom of society ally against the middle class1, ultimately resulting in poverty for all but the upper elites; or

a dictatorship where one man at the very top allies with the middle class against the upper class oligarchy and bottom, resulting in a relative egalitarianism so long as leadership is strong and stable.2

By the time of Julius Caesar, Rome’s oligarchy in the guise of a “republic” had become decadent and corrupt and the nation was spiraling into the abyss, having lost its virtues in the opulence and wealth gained after defeating Carthage in the Punic Wars.3 Rome was lucky to have a man come in and accept responsibility for the affairs of the state, as the alternative was simply dissolution. One man being responsible for the direction of a nation makes that man acutely sensitive toward maintaining stability and prosperity, otherwise his head will be on the line. The downside of one-man-rule is a conspiracy can kill him (oligarchy is much more resilient against murder or overthrow), along with uncertainties around succession - who will become the next emperor and what kind of emperor would he be, good or bad, weak or strong?

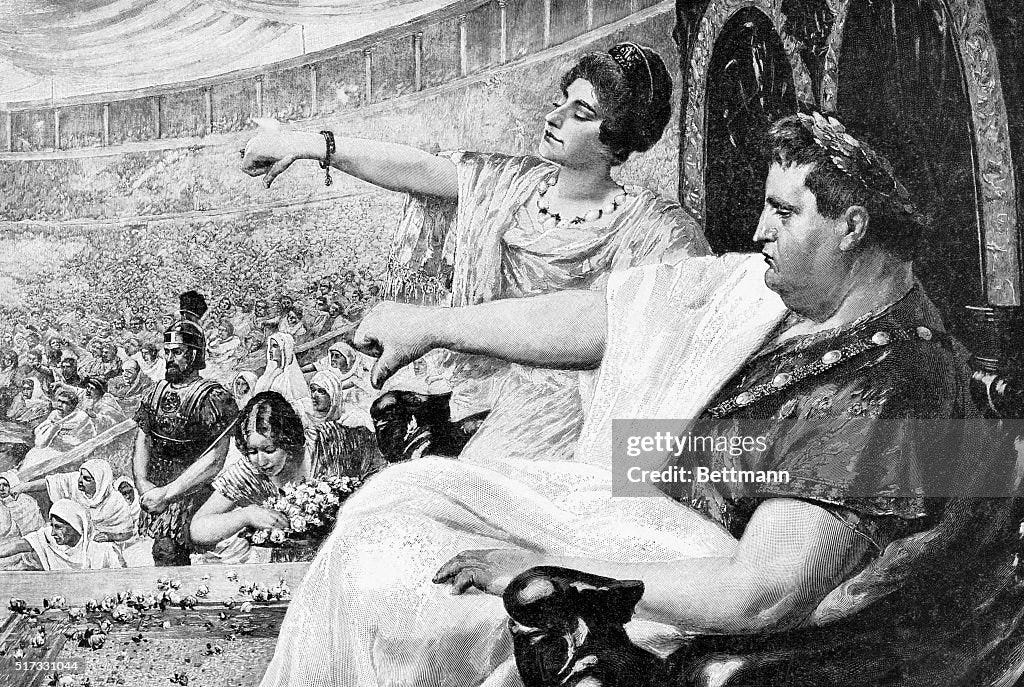

We think of Roman emperors as almost God-like deities who had total power in their hands: the ability to take life at a whim, the ability to order war, to have sex with anyone’s wives or engage in orgies, to make and change laws however they wished.

In reality, though, emperors were enormously restricted by politics. They were mortal and there was danger to their lives lurking around every corner, with the Sword of Damocles hanging by a hair over their heads. Let’s recount that story:

As Cicero tells it, [King Dionysius II of Syracuse]’s dissatisfaction came to a head one day after a court flatterer named Damocles showered him with compliments and remarked how blissful his life must be. “Since this life delights you,” an annoyed Dionysius replied, “do you wish to taste it yourself and make a trial of my good fortune?” When Damocles agreed, Dionysius seated him on a golden couch and ordered a host of servants to wait on him. He was treated to succulent cuts of meat and lavished with scented perfumes and ointments.

Damocles couldn’t believe his luck, but just as he was starting to enjoy the life of a king, he noticed that Dionysius had also hung a razor-sharp sword from the ceiling. It was positioned over Damocles’ head, suspended only by a single strand of horsehair. From then on, the courtier’s fear for his life made it impossible for him to savor the opulence of the feast or enjoy the servants. After casting several nervous glances at the blade dangling above him, he asked to be excused, saying he no longer wished to be so fortunate.

For Cicero, the tale of Dionysius and Damocles represented the idea that those in power always labor under the specter of anxiety and death, and that “there can be no happiness for one who is under constant apprehensions.” The parable later became a common motif in medieval literature, and the phrase “sword of Damocles” is now commonly used as a catchall term to describe a looming danger. Likewise, the saying “hanging by a thread” has become shorthand for a fraught or precarious situation.

Danger could arise from usurpers, from wives murdering the line of succession or even their husband to set up their own children as future emperors, and from the Praetorian Guard, who were supposed to protect the life of the emperor but who grew into a kingmaker role. Indeed, being emperor was such a dangerous job (both to themselves and to their family members, such as Livia’s systematic removal of Augustus’ heirs until her own son, Tiberius, was the prime candidate), prone to treachery (Claudius being poisoned by his wife Agrippina) and overthrow, that out of almost 60 imperial reigns regarded as legitimate there was around thirty overthrows and 105 usurpations, an insanely high number. Emperors and their families were at such high risk that Julian’s prefect Salutius thought the position was cursed and turned it down when offered it, as did others at various points in Roman history such as Verginius Rufus and Triarius Maternus Lascivius (who lost his clothes trying to get away from the soldiers trying to force him to accept). It is more surprising, then, that the position was still so desperately coveted by so many, despite how few lived out their natural lives as emperor. Hope, pride, ambition and glory spring eternal, I guess. And if you become emperor, even for a moment, you enter the history books.

This post is about the relationship between the Praetorian Guard and the office it was supposed to protect and how those roles evolved over time. Why is it relevant? Because as much as we love the concept of separation of powers in America, it is a lie, and power always rests somewhere, whether overt or covert. What is this power? What Carl Schmitt referred to with the excellent expression, "Sovereign is he who decides on the exception". After all, quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

In America’s case power rests primarily with the central bank owners who own the Federal Reserve (which prints money out of thin air and then lends it at interest to the government), but secondarily with the transnational security elite. These security elites are represented domestically by the FBI and CIA, along with the “five eyes” of Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Canada who, as one example, routinely spy on each other’s citizens to get around domestic spying laws. These organizations can make or break any president, senator or congressman — as Chuck Schumer said, “Let me tell you: You take on the intelligence community — they have six ways from Sunday at getting back at you”. Examples include likely having a role in assassinating Kennedy; unjustly taking down Nixon (on a spying allegation that has been dwarfed by Obama’s intense and comprehensive spying operation on his political opposition); appointing former CIA director George H.W. Bush as president and extending their loyalty to his idiot, arrogant neocon man-child son; and stymying the presidency of Trump in a dozen different ways. Look how Speaker Johnson was just skin-suited, or at how these organizations used lawfare to bankrupt Alex Jones. The CIA and FBI (and to a lesser extent the NSA and DOJ) are the modern day Praetorian Guard, the kingmakers behind the scenes.

Now, I have discussed the tactics of these transnational security elites previously - see here if you want to read the grisly details - but seeing these same types of people use and abuse their power during the heyday of Rome reinforces the concept that ultimate power will always rest somewhere, and the best thing one can hope for is to tie responsibility to power. In other words, everyone should know who is actually in control so they can be blamed if things go wrong, as opposed to getting mad at figureheads, parties or institutions that don’t actually have real power like we do with the figurehead puppet politicians of the central bank owners.

Let’s go through the history of the Praetorian Guard, how they operated, and why they were so feared. Much of the below information is from Guy de la Bedoyere’s excellent and readable “Praetorian: The Rise and Fall of Rome’s Imperial Bodyguard”.

The creation of the guard

During the Roman Republic there was no formal Praetorian Guard. Instead, there were generic soldiers placed on details to guard their commanding officer. Julius Caesar did employ a body of 400 loyal German cavalry during the Gallic Wars which he habitually kept with him, but those foreign troops were not the Guard. In 44 BC he dismissed a bodyguard made-up of Spaniards, a moment of arrogant overconfidence that contributed to his unprotected assassination. Caesar was convinced that possession of a bodyguard was a sign of a man who lived constantly in fear of death, and he decided unwisely to rely on popular goodwill for protection. These events were portrayed in the wonderful TV series Rome, which I highly recommend.

During the civil war that followed between Octavian and Antony, Octavian’s bodyguard of ten thousand grew mutinous when Octavian suggested sending them to fight against Antony. Octavian had to back off, fast, and he told the soldiers they would only be needed for emergencies and promised them more money to calm down. Octavian learned an important lesson about a bodyguard of troops: they could be bought, but only under certain conditions, that their vanity needed flattering and that they needed organizing. Another time soldiers almost rioted and killed Octavian over a misunderstanding during a demonstration of games when he had no bodyguard, and another time when starving rioters in Rome stoned and almost murdered him. When Octavian finally secured supreme power in 31 BC, he vowed not to make the same mistake that Julius Caesar had made. This led to the creation of the Guard which would have to swear loyalty to Octavian personally, something that would later transfer to other emperors.

Octavian, re-styled as Augustus, created the Guard to control the Senate and coerce the Roman aristocracy on his behalf; he would never let himself be put in a situation where the Senate could conspire to assassinate him. He made the Guard permanent and set up the urban cohorts (a military city police force) as a kind of less-prestigious check on and rival to the praetorian’s power. There were not many plots against him, though, because Augustus’s supremacy was unquestioned and no one wanted to return to the chaos of the civil war years. The Guard did foil one plot by a group of senatorial conspirators led by one Fannius Caepio but they were found out and quickly executed. But it was a precarious balance as the emperor needed to have more prestige and influence than the Guard if he was to maintain control, something many future emperors lacked.

Composition of the guard

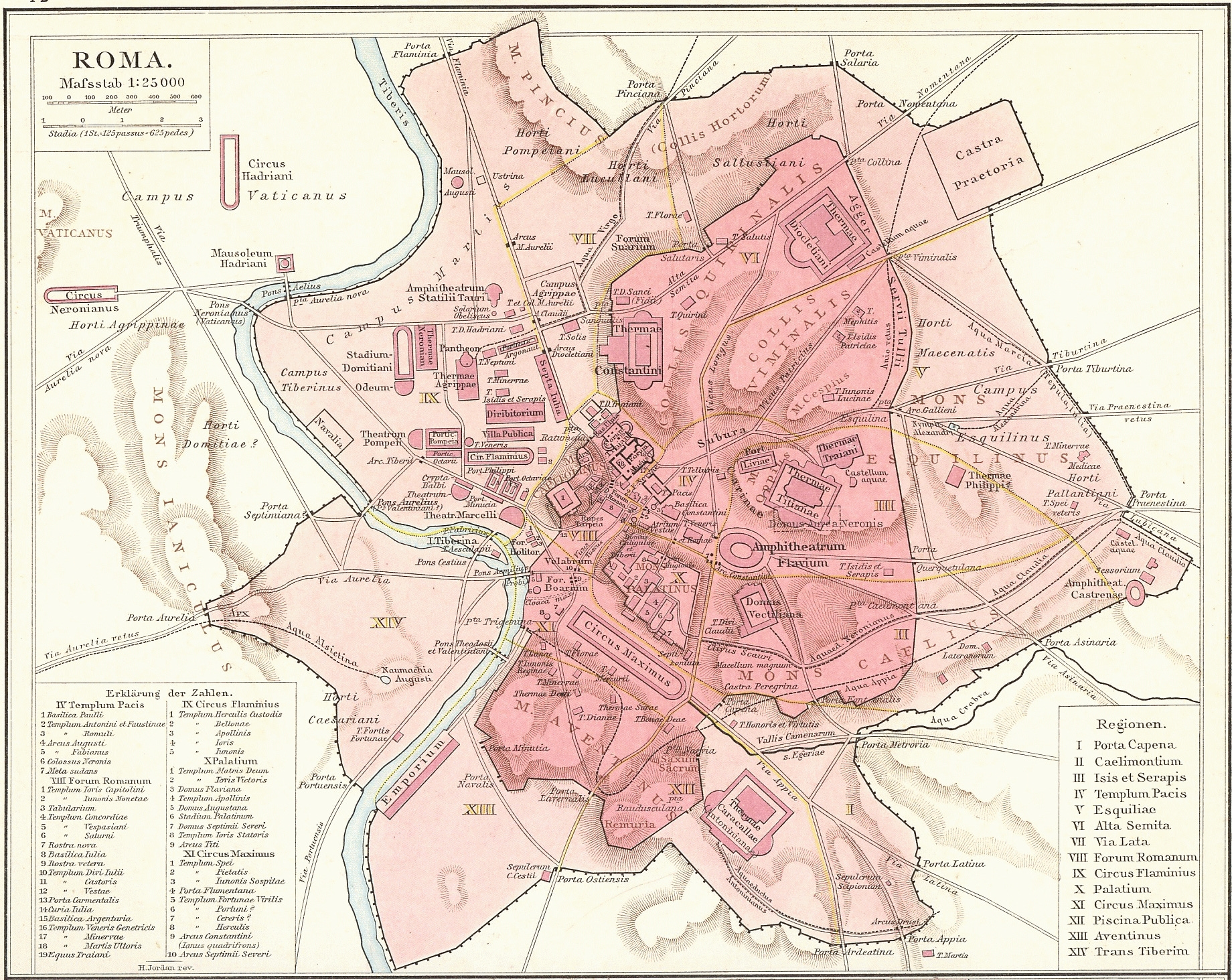

Praetorians were named for a general’s tent or residence on campaign, the praetorium. The word was derived from the word praetor meaning ‘the man who goes before others.’ It was comprised of roughly 8,000-10,000 soldiers (but the numbers differed wildly depending on the era), much better pay (double that of normal legionaries)4 and its members served less time (16 years generally versus the 20 for normal soldiers), it was more prestigious than any of the other armed forces and located right outside Rome during the reign of Tiberius at a place called the Castra Praetoria. This location so close to the center of power served as an ever-looming and sinister influence on those seeking to hold office within Rome itself.

The Guard were sometimes depicted as privileged bullies as they possessed certain powers and immunities that others lacked: they could thrash a civilian without fear of redress and their court cases would be heard immediately before anyone else, as just two examples of their privilege.

The Guard was recruited from freeborn Italian Roman citizens aged from their mid-teens to as old as thirty-two, which would remain stable until 193 when Septimius Severus switched recruitment to deserving soldiers from any legion. Command of the Guard went to a man of the equestrian rank (second-grade aristocrats) called the praetorian prefect because if it went to a man of senatorial rank he would be much more likely to try to overthrow the emperor to seize power. Men of equestrian rank were not eligible to hold supreme power. This position of praetorian prefect was one of considerable power and influence to the point where the incumbent could play a dramatically important role in influencing Roman imperial rule, such as Sejanus under Tiberius who came extremely close to toppling the emperor (and his successor Marco may have murdered Tiberius), while Tigellinus under Nero and Perennis under Commodus wielded extraordinary control.

Evolution of the Guard

After Augustus’s reign the Guard, like any institution, was gradually replaced by new generations that had no understanding or memory of life before its existence. They became enmeshed in their positions, comfortable in them, and then gradually came to feel entitled to them, especially as younger emperors who had less experience than those in the Guard came to the throne. We can see the same thing today in the U.S. civil service which has an extreme element of entitlement and hatred toward middle America which they see as threatening to their sinecure, as

points out. Gibbon commented on the Guard:Such formidable servants are always necessary, but often fatal to the throne of despotism. By thus introducing the Praetorian guards, as it were, into the palace and the senate, the emperors taught them to perceive their own strength, and the weakness of the civil government; to view the vices of their masters with familiar contempt, and to lay aside that reverential awe, which distance only, and mystery, can preserve toward an imaginary power. In the luxurious idleness of an opulent city, their pride was nourished by the sense of their irresistible weight; nor was it possible to conceal from them, that the person of the sovereign, the authority of the senate, the public treasure, and the seat of Empire, were all in their hands. To divert the Praetorian bands from these dangerous reflections the firmest and best established princes were obliged to mix blandishments with commands, rewards with punishments, to flatter their pride, indulge their pleasures, connive at their irregularities, and to purchase their precarious faith by a liberal donative; which, since the elevation of Claudius, was exacted as a legal claim, on the accession of every new emperor.

On the topic of Claudius, the Guard elevated him to emperor after they helped a number of disaffected senators assassinate Caligula because they desperately needed someone, anyone to be emperor, without which the Guard would no longer have a secure position and be entitled to status and pay. Claudius was from the correct bloodline despite being a semi-invalid. Claudius reluctantly offered the praetorians a remarkable sum of money which marked the first - but not the last - dubious occasion where outright bribery was used to secure the Guards’ loyalty.

Per Bedoyere, the power that the Guard came to wield to raise or destroy emperors was immense:

The Guard’s ambitions, and those of its prefects, expanded to fill the voids left by inadequate or vulnerable rulers. Thus, Tiberius’ self-imposed exile to Capri made it possible for the praetorian prefect Sejanus to try to become emperor himself. The disastrous reign of Caligula in 37-41 led to his assassination to the Guard appointing its own emperor in the form of Claudius. The loss of the Guard’s support played a key part in Nero giving up and committing suicide in 68. During the civil war of 68-9 the Guard played crucial roles in the fight between the rivals for the Empire. In the second century AD the succession of strong and effective rulers meant that from 98 until 180 the Guard rarely appears in ancient sources. The dereliction of the reign of Commodus (180-92) brought the Guard back to the fore once more and it was the behavior of the praetorians that led to the murder of Pertinax and the brief and tawdry reign of Didius Julianus. In volatile and unsettled times the Guard acted as catalysts and opportunists, and their prefects as major players, for good or ill.

The role of the Guard evolved over time too. Originally it was to protect the life of the emperor, but then it was increasingly used to carry out sensitive tasks, perform tax collections, law enforcement, assassinations of the emperor’s enemies (such as Tiberius having the Guard murder Augustus’s last grandson by Agrippa, Agrippa Postumus), and serve as administrators across the Empire. And like most institutions, they gradually came to embody the inverse of what their original function was; i.e. they could kill and overthrow emperors on a whim. That being said, the Guard remainder symbiotically attached to the position of emperor for without an emperor to “guard” there would be no guard, no high status and no pay. In much the same way that without constant “threats” to America the CIA and FBI would not have justification for their control and power, and continued funding - even though most or almost all of these so-called “threats” were created and propagated by these organizations in the first place.

One interesting anecdote of how the Guard was used was the story in 61 AD of Lucius Pedanius Secundus, the prefect of Rome, who was killed by one of his slaves. This story also highlights how strange and different Rome’s morals and ethics were compared to ours today:

The motive is not clear; the slave had either been denied his freedom after it had been agreed or had challenged his master for the affections of another male slave in the household. The traditional legal response to such a dramatic situation was to execute all the slaves on the grounds of collective guilt. This excited a popular protest, which degenerated into riots after the senate ordered that the law must take its course. Nero stood fast and ordered praetorians to line the route along which the condemned slaves were led.

Corruption of the guard

Any man that ascended to the role of emperor became expected to give the Guard a massive donative. In search of a promised reward, they abandoned the reigning emperor Nero but only because Galba seemed a better financial prospect. When Galba failed to pay they turned on him too: “By 68 a very distinct pattern had formed. The praetorians had emerged as the single group of people whose support, or lack of, could make or break an emperor. Their headquarters, the Castra Praetoria, was turning into the place where emperors and senators went to seek support. Nevertheless, the end of Nero’s reign marked a new twist. This was the first time the praetorians had broken their oath to a living emperor….the revelation that the Guard’s loyalty was transferable was an uncomfortable discovery, firstly for Nero.”

In the second century AD a series of strong and competent emperors contributed to a period of stability where the Praetorians had no opportunity or perhaps wish to play a part in toppling or appointing emperors, and they spent much more time in the field fighting in the emperor’s various wars.5 But the death of Marcus Aurelius and the ascension of his weak and reckless son Commodus created a power vacuum into which the Guard was sucked into and the praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus participated in a successful plot to kill him. In the space of five months they installed another emperor and then abandoned him with unseemly haste. The appalling spectacle is worth quoting at length:

On 28 March AD 193 the emperor Pertinax was murdered after a reign of just eighty-seven days. His efforts to rule Rome with integrity and order had been generally welcomed. The Praetorian Guard, Rome’s spoilt, privileged and elite imperial bodyguard was the most conspicuous exception. Pertinax had tried to instill meaningful discipline among the swaggering praetorians, who had become accustomed during the reign of Commodus to behaving as badly as they pleased, including hitting passers-by. To soften the impact of the new rules, Pertinax had promised the Guard 12,000 sestertii each, claiming he was matching what Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus had paid them on their accession in 160….The praetorians, however, took exception to the idea they might return the favour by improving their behavior. After all, they were aware that Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus had actually paid 20,000 sestertii to their predecessors and that Pertinax had possibly only ever paid half of what he had offered. The praetorians killed Pertinax but, terrified of the consequences of what they had done, they dashed back to their camp, the Castra Praetoria, and locked the gates.

Strangely, everything quieted down and the praetorians realized no one had come after them. Fully aware now that they were the ones who were really in charge, they posted a notice at the Castra Praetoria offering the Roman Empire for sale….

The praetorians capitalized on the fact that no one could hope to be emperor without their backing. Didius Julianus and Flavius Sulpicianus, each desperate for supreme power, started making rival cash offers to the Guard. The soldiers enthusiastically threw themselves into the auction, running across the camp between the candidates to tell each how much he would have to raise his bid by. Sulpicianus was about to win with an offer of 20,000 sestertii per praetorian when Julianus seized the day with a reckless counter bid of 25,000. Julianus added added for good measure the warning that Sulpicianus might seek revenge for the death of Pertinax and also that he, Julianus, would restore all the freedoms the praetorians had enjoyed under Commodus. So delighted were the praetorians by the new offer they promptly declared Julianus to be the new emperor.

This event was so extraordinary, tawdry and demeaning that even now it seems barely credible that the Roman Empire could have stooped so low. Herodian described it as a decisive turning point, the moment when soldiers lost any respect for the emperors and which contributed to so much of the disorder that was to follow in the years to come. The Praetorian Guard had brazenly created an emperor purely on the promise of a huge cash handout, consummately and nakedly abusing their position and power. Julianus lasted even less time than Pertinax, having injudiciously offered far more money than he could afford. He was executed on the orders of the senate just sixty-six days after he was made emperor.

What a morbid but funny story.

The Guard’s downfall

The downfall of the Guard came about when they backed the wrong horse in the civil war between Constantine and Maxentius. This culminated in the battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, which was also the impetus for Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. Constantine’s victory signaled the final conquest of the upstart religion over the Hellenic world, with a brief but doomed attempt by Julian the Apostate to reverse it which I covered previously here.

After Constantine’s victory he disbanded the Guard permanently and dismantled the Castra Praetoria. This did not mean that Constantine did not need a bodyguard, he did, but the Guard had become a liability, undermining the emperor and creating a lot of instability. “In an era when the emperor needed to be able to move with exceptional rapidity around his fragmenting empire and deal with remote rebellions or frontier incursions, an armed bodyguard with a fortified base in Rome was a colossal liability.” Constantine instead created a mounted palace bodyguard, much smaller in number and answerable directly to the emperor instead of to a prefect, which drastically reduced the risks inherent in having a bodyguard - but also removed much of the power and prestige associated with the position.

Everything has an end and just as the Guard eventually met its own end at the twilight of the Hellenist era and the emergence of the Christian era, our transnational security elite and the unelected civil service will also have their own end down the road, in whatever surprising, circuitous and perhaps tortured direction it may take; perhaps it will take the beginning of a new era, with new and strange values, before it meets its own end.6 After all, the Guard lasted for more than three hundred years through long periods of shocking corruption and decadence — and as we are seeing now, the unelected civil service is burrowing in like a tic on their entrenched positions and dramatically expanding their power and spying apparatus.

Thanks for reading.

At its best, ancient Greece or early America which allowed individual liberty to flourish. At its worst, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot.

At its best, Lee Kuan Yew and Augustus. There are many historical examples of poor dictators due to corruption, weakness, and militant aggression.

Interestingly, soldiers did not receive their pay until they were discharged, less deductions for equipment. This may explain the added attraction of accession donatives paid by new emperors to praetorians. Additionally soldiers, including praetorians, were not allowed to marry during their service (as it would decrease their willingness to fight) although many had unofficial wives.

Given the Guard existed to protect the emperor, when the emperor was leading a campaign it makes sense that they also participated in those campaigns.

The way trends are going that would likely be the ascension of Islam in the West.

What a great piece. I think you’re exactly right about the analogy between the Praetorian Guard and the security services of today. Do you think it’s naïve to think there is occasionally a third thing between democracy/republicanism and dictatorship where for brief moments of history we might have a ruler who unites his lords in the shared pursuit of virtue? Plato thought the sword of Damocles hung over tyrants, because they had to use fear or manipulation to control the men around them. That’s why the tyrant is the most unhappy of men. Plato’s idea of a philosopher king is someone who does not suffer in this way because his men understand that he is doing what is right. It's the kind of leadership a father has in a family, and I guess we have the archetype of Camelot for this...

Fantastic! It seems this is the nature of humans and government institutions throughout history; in that, what starts out as necessity morphs into corruption, greed and rot as the people employed to carry out the tasks become drunk on power and use their status and/or position to enrich themselves to the detriment of society as a whole.

I read somewhere that the most cohesive and benevolent society is compromised of around 150 people. Past that, those empowered to make decisions have less regard to make any decisions that don't directly benefit themselves.