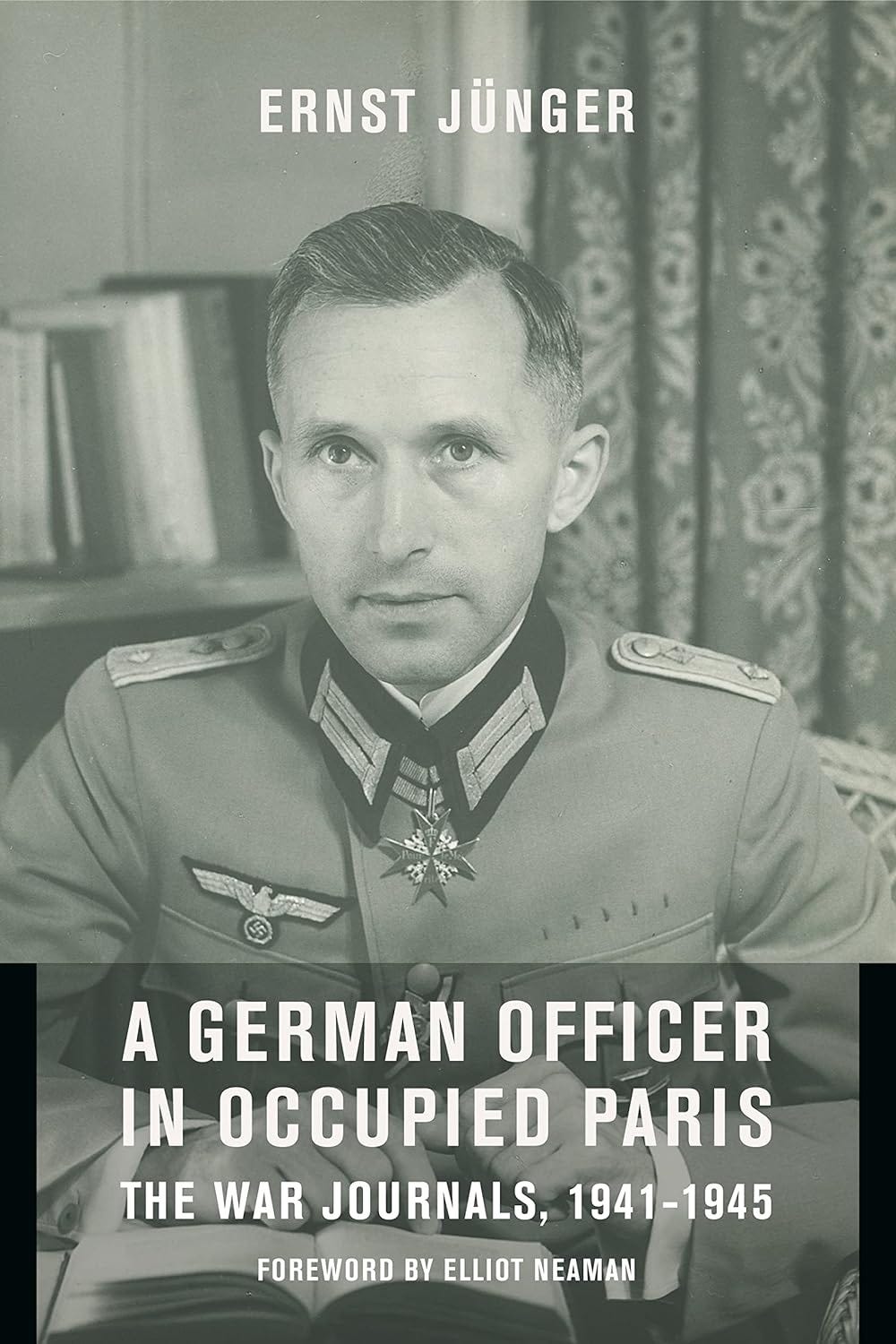

This is a post about one of the most unique and complicated authors of the 20th century, Ernst Jünger. The power of his writing comes not so much from his insights but from the unusual internal conflicts that he embodied, which in turn stimulates deeper thinking on behalf of the reader. Reading Jünger is difficult but rewarding and will further your spiritual development if you decide to engage with him.

“Some people had dirty hands, some had clean hands, but Jünger had no hands.” - Jean Cocteau

“When I studied the documents, I was often astonished by [Hitler’s] intransigence in minor differences (to put it diplomatically), for example, in the dispute over the heads of a handful of innocent people. We will never grasp this if we cannot see through his desire to destroy the nomos [law, customs], which guides him infallibly. This can be expressed impartially: He wants to create a new standard.” - Jünger on Hitler

I recently read the recent English translation of Ernst Jünger’s 1941-1945 war journals, and for once (ha) I am at a loss of words. There are so many ideas highlighted within his contradictory writing, but the core themes relate to stoicism, faith, the importance of individualism and staying true to one’s values. The hope is that by delving into Jünger’s worldview it will shine light onto our own development and journeys. Perhaps it may also highlight ways for us to resist globohomo’s dictates even if we outwardly abide by them, at least to an extent, much as Jünger remained unconquered within even as he externally complied to an extent with the existing mileau.

Jünger’s background

For background, Jünger was a highly celebrated World War 1 German war hero and author who volunteered early to fight. He treated war as an adventure. Most famous for his Storm of Steel novel which glorified war for its own sake, he was wounded fourteen times in battle, including five bullet wounds and became the youngest recipient of Germany’s highest military honor, the Pour le Mérite at 22 years old. Awarded it by Ludendorrf, per Jünger, the ancient general warned him “‘it is dangerous for one so young to be decorated with the highest honour.’ Back then I considered it pedantic, but today I know that it was right.”

Jünger started what became an illustrious writing career which gave him unusual access to hobnob with influential authors, poets, artists, politicians and other intellectuals across the political spectrum. He served in a cushy military role in World War 2 even though his antipathies to the Nazi regime were public knowledge: he warned Germany would lose against Russia in his prescient 1939 allegory On the Marble Cliffs1 and publicly refused Nazi entreaties to become their ally. He was within the circle of aristocrats that conspired against Hitler in the July 20 plot and served as an inspiration by writing The Peace but declined to participate, and closely survived being executed. “Nothing happens to Jünger,” Hitler apparently said.

Surviving the war, he wielded much influence in the fifty years he lived beyond it. The older Jünger lost his taste for battle’s glittering accoutrements when World War 2 turned into a war of de-personalized butchery: “I am overcome by a loathing for the uniforms, the epaulettes, the medals, the weapons, all the glamour I have loved so much. Ancient chivalry is dead; wars are waged by technicians.” Yet after the Allies won he refused to undergo denazification, remaining firmly against democracy, and he despised the liberals who had given themselves over “completely to the destruction of the old guard and the undermining of order”. Still, over the decades he became highly decorated by the liberal order for his literature and scientific achievements.

Most of Jünger’s post-World War 2 work touched on man's relationship to technology and the struggle to retain individualism in light of mass social conformity and technology pressures (see his novel The Glass Bees). But because Jünger’s aristocratic, anti-democracy, mystical perspective was so inaccessible to western audiences, only eleven of Jünger’s fifty-nine works have been translated into English. This is unfortunate and hopefully will be remedied in the future.2

Junger’s contradictions

Jünger’s wartime journals - four of the six translated into English in this edition3 - were not what I was expecting. I was expecting a narrative like his adventurous, war-loving Storm of Steel, but instead the journals have a mystical, contemplative feeling reflective of Jünger’s advancing age (he was approaching 50). They focus on dream interpretation, astrology, his growing beetle collection and the various famous figures he socialized with after the conquest of France where he was stationed in an administrative capacity. There is little political or military discussion in the first half of the book and not a large amount thereafter. Despite the unmet expectations, the surrealism and strangeness of the esoteric writing draws one in - there is a feeling that the significant time demanded will be rewarded, and it is.

Reflecting on his journals, it is not so much of what Jünger wrote which was profound but rather the astonishment at how so many contradictions could be held within the body and soul of one man. Compounding the issue of understanding is that his character was forged in a time and environment with very different values compared to the ubiquitous egalitarianism of today. As Jünger writes,

When viewed politically, man is almost always a mixtum compositum [hodge-podge]. Time and place exert huge demands upon him.

In this sense, when seen from the ancestral and feudal perspective, I am a Guelph, whereas my concept of the state is Prussian. At the same time, I belong to the German nation and my education makes me a European, not to say a citizen of the world. In periods of conflict like this one, the internal gears seem to grind against each other, and it is hard for an observer to tell how the hands are set. Were we to be granted the good fortune to be guided by higher powers, these gears would turn in harmony. Then our sacrifices would make sense.

It is Jünger’s commitment to listening to his own voice and not being internally swayed by the crowd, as well as his personality contradictions that stimulates deep thought on the part of the reader. By observing how he navigated his inconsistencies perhaps we can further our understanding of our own.

Jünger seemed to feel the following conflicting impulses:

A deep aristocratic feeling which made him disdain the middle class and populism even as he extended his sympathies to the lower class. This feeling grew as he aged and likely played a role in his disdain for Nazism, a movement he had initially quasi-embraced.4 He called The Myth of the 20th Century by Rosenberg “the dullest collection of hastily copied platitudes imaginable.”

“In my dealings with people, I have noticed that I do not speak much to the middle sort, whether of intelligence or character. My contact with very simple as well as highly developed natures, however, presents no difficulty. I seem to resemble a pianist playing only the keys at the extreme ends of the keyboard and just having to make do without the rest. It’s either peasants and fishermen or people of the highest quality. The rest of my social dealings consist of arduous attention to the mundane - rummaging through my pockets looking for change. I often get the feeling that I am moving within a world for which I am not adequately equipped.”

A strain of honor and chivalry where he felt more horror at Germany’s breaches of these values than he felt at similar or more extreme tactics used by its enemies. Jünger strangely seemed to feel more horror felt at Germany’s use of collective punishment, including its targeting of the Jews5, versus the Allied bombing of Dresden which killed 200,000 Germans. It’s possible some of this influence had to do with Jünger’s mistress who he considered leaving his wife for, Sophie Ravoux, a German-Jewish doctor.

“It is appalling how blind even young people have become to the suffering of the vulnerable; they have simply lost any feeling for it. They have become too weak for the chivalrous life. They have even lost the simple decency that prevents us from injuring the weak. The opposite is true: they take pride in it….I never allow myself to forget that I am surrounded by sufferers. That is more important than any fame achieved through military or intellectual exploits, or the employ applause of youth, whose taste is erratic.”

“Two young officers from the tank corps sitting by the window; one of them stands out by virtue of his fine features, yet for the last hour they have been talking about murders. One of them and his comrades wanted to do away with a civilian suspected of spying by throwing him into a lake. The other man expressed the opinion that after every time one of our troops is murdered, fifty Frenchmen should be lined up against the wall: “That will put a stop to it.”

I ask myself how this cannibalistic attitude, this utter malice, this lack of empathy for other beings could have spread so quickly, and how we can explain this rapid and general degeneration. It is quite possible that such lads are untouched by any shred of Christian morality. Yet one should still be able to expect them to have a feeling in their blood for chivalric life and the military code, or even for ancient Germanic decency and sense of right. In principle they aren’t that bad, and during their short lives, they are willing to make sacrifices worthy of our admiration. We can only wish that the words “above reproach” might be added to their unassailable motto, “without fear.” The second has value only in conjunction with the first.”

A keen Christian sensibility with a strong belief in the afterlife while seemingly believing in the existence of other Godly powers and energies. He wrote, for example, “The ancient gods still stand before us with their magical presence, perhaps even in competition,” intending it literally. Still, he read both the Old and New testaments front-to-back twice in the four years covered in the diaries which offered him peace of mind. His Christian sensibility likely played a significant role in both his philo-semitism and his understated anti-racism beliefs.

“What can one advise a man, especially a simple man, to do in order to extricate himself from the conformity that is constantly being produced by technology? Only prayer. Here even the lowest human being has a vantage point that makes him part of the whole and not just a cog in the machinery…In situations that can cause the cleverest of us to fail and the bravest of us to look for avenues of escape, we occasionally see someone who quietly recognizes the right thing to do and does good. You can be sure that is a man who prays.”

A scientific eye for detail balanced against feelings of mysticism. The former is seen in entomology research (multiple types of beetles were eventually named after him), while the latter is reflected in his belief in strange omens, premonitions and prophecy, his dabbling in astrology and the occult, seeing synchronicity everywhere, and his fascination with dream interpretations. Dreams to Jünger represented the connection between the temporal and the spiritual worlds; it is where we communicate with the dead and with our innermost self. As World War 2 dragged on and the sense of German hopelessness grew, the line between dream and reality increasingly blurred.

A friend to those across the political spectrum from the left and far-left (Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Toller, the anarchist Erich Muhsam, the National Bolshevisk Ernst Niekisch) to the right and far-right (Gottfried Benn, Ernst von Salomon, Arnold Bronnen, Carl Schmitt) so long as they did not possess middle class sensibilities. He met with prominent figures like Picasso and Braque in their studios and debated their art in fluent French, pondered the meaning of dreams with Jean Cocteau, along with science, poetry, the military and politics. “Some people had dirty hands, some had clean hands, but Jünger had no hands” wrote Cocteau as he blended in, chameleon-like, with whoever he was with.

Despite his wide circle of friendships, Jünger possessed an emotional aloofness, detachment and arrogance (a “statue of ice” in the words of one acquaintance) which separated him from them all. The Gestapo had described him at his period in Paris as "an impenetrable, highly suspect individual" and even his wife felt his emotional coldness. Jünger wrote, “The fact that I love the most elusive, and probably also the best, in them - that may be the source of the coldness they perceive in me.” And he refers to the hyper-acute sense of observation “with which I am cursed, the way others have an especially keen sense of smell. I detect the shady moves that are endemic to humans are too clearly.”6

His focus was on a level above politics, focusing on the spiritual. His politics, to the limited extent he shared them, were aristocratic and anti-democracy, but he displayed little of the brilliance when Guido Preparata described the strategies employed by the British and American financial powers for world domination in “Conjuring Hitler”.7 Jünger’s thoughts were elsewhere. Even in his “On the Marble Cliffs”, easily seen as a parable for a German invasion of Russia and its subsequent defeat, he attempted to dismiss at the level of political analysis:

“I would also like to add, even though I think an author should respect the rule of never talking about his books, that in the case of Marble Cliffs the political effect was secondary for me. Some friends have reproached me for downplaying this effect, which for many was the most important one. However, I prefer to draw attention to the fact that in that case I placed myself on another level. After all, it is clear that if mine had become a political stance, I might have found companions and followers, but I would have fallen at the same level as Hitler. I was his opponent, but not a political opponent. I was simply in another dimension.”

Jünger served in the German armed forces in World War 2 despite his ideological misgivings. He referred to Hitler throughout his journal as Kniébolo, meaning roughly “kneel to the Devil”, even though Hitler refused to let harm come to him after publishing On the Marble Cliffs8 or even after the July 20 plot. As a man who favored martial values Hitler had a great respect for Jünger’s World War 1 service and writings. Jünger wrote of Hitler, “I sometimes have the impression that the world spirit has chosen him in a subtle way. There are secrets here that other tribes will never comprehend.”

A warrior with an inborn love of dangerous adventure who eagerly put his life in harm’s way early on without ideological motivation, expecting to die very young, and yet who lived to 102 years old (converting to Catholicism shortly before his death). Writing at the age of 65, “I have now reached the biblical age of three score and ten - a rather strange feeling for a man who, in his youth, had never hoped to see his 30th year. Even after my 23rd birthday in 1918, I would gladly have signed a Faustian pact with the Devil: "Give me just 30 years of life, guaranteed, then let it all be ended.”” He truly had luck on his side when it came to his friendships and his health. And his mind stayed sharp up until the end, learning and absorbing new information even as others far younger developed rigid thoughts and habits. He wrote, “In order to grow old, we have to stay young.”

However, his oldest son Ernstel followed in his footsteps but died very young, killed in early 1945 in Italy.9 The most touching part of the diaries is about the loss of his son. You can read the details by

here.Jünger’s relationship with death was complicated and strange. He had a sense that this life is simply a tryout for values brought with us in the afterlife. While many people mouth these platitudes in the modern era, Jünger believed it. Echoing Diogenes of Sinope, he wrote “What is left of us from this life if we do not accumulate worth that can be exchanged for gold at the tollgate of death’s realm, to be exchanged for eternity?”10

Although a man of bold action early in his life, by World War 2 he had become a man of external passivity. With respect to his circle’s plot against Hitler, Jünger argued that historical precedents showed that assassinations of leaders led to greater tyranny, and he was worried that if it was successful it would lead to a new Stab-in-the-Back legend. Jünger merely offered moral support and narrowly avoided being targeted by retribution after the July 20 plot failed. Ultimately he was merely dismissed from the army.

“The individual of historical importance has his own aura, his superior necessity, a power that repels [assassination]. Napoleon’s statement applies here: As long as he was under the spell of his mission, no power on earth could bring him down, whereas after he had fulfilled his mandate, a speck of dust would suffice.”

Despite the conservative milieu of the time and his aristocratic, warrior background, Jünger experimented with drugs in order to access different planes of existence. He was one of the first to try LSD; he met with LSD inventor Albert Hofmann and they took it together several times, and he experimented with cocaine, ether and hashish. He later wrote a book about it.

After the war Jünger was targeted as a Nazi, although the label didn’t really stick. His leftist friends such as German playwright Joseph Breitbach vouched for him, stating that he had saved others when the risk to himself was at an acceptable level, he had never joined the Nazi party, the Gestapo had searched his home multiple times and he predicted they would lose in his On the Marble Cliffs. Still, Jünger refused to undergo denazification. Decades later he became quasi-lauded by the globohomo establishment for his books, while some on the far right considered him a traitor. According to Aris Roussinos,

Just as he did with Hitler’s regime, Jünger lived and died a dissident against the liberal regime that replaced it, outwardly conforming but never submitting. He despised democracy just as he despised the gullible and easily-swayed demos who had brought Hitler to power. And he despised the liberals who had given themselves over “completely to the destruction of the old guard and the undermining of order”, setting in train the nightmares of the 20th century, just as he despised the “young conservatives who first support the demos because they sense its new elemental power, and then fall into the traces and are dragged to their deaths”.

Tying the character puzzle together

It is hard to combine these contradictory elements into a unity, but the core seems to me what Jünger later described in his 1977 Eumeswil novel as an “anarch”: participating in life as required by society to the extent necessary for survival, while retaining an internal independence of mind and spirit that cannot be controlled by outside influences. One gets the sense reading his work that he marched to the beat of his own moral compass, and at least internally had a rich inner world others could never reach. There are no historical figures akin to Jünger; he is in a class of his own.11 As much as he studied the characteristics of beetles with his entomology hobby, his real character study was that of other humans who he viewed as a kind of alien watching their behavior and motivations from the outside. He writes of his impulse to observe the war’s characters “as if these were creatures like fish in a coral reef or insects on a meadow”. I too feel like a perpetual outsider to all groups, watching human behavior in a similar fashion.

The unique combinations and contradictions in Jünger’s personality manages to zigzag around a reader’s preconceived, built-up defenses to consider new ideas with an open perspective. It is in a way like Nietzsche’s perspective who felt that only by addressing contradictions could one hope to reach a synthesis where the truth might lie. According to Ayn Rand’s Atlas Society,

“Nietzsche’s concept of knowledge did not only allow for contradictions. It required them. Only total, comprehensive knowledge, which incorporated opposite opinions, was true knowledge for him. Thus, it was possible for him to write for and against Judaism, for and against Christianity, for and against racism. The National Socialists could interpret his writings any way they wished and manipulate them for their ends because of Nietzsche’s explicit rejection of reason and logic.”

Jünger’s contradictions were less explicit than Nietzsche’s, of course. He engaged in some unstated emotional process that manifested in ambiguous phrases and turns of expression which themselves contained the competing ideas.

Jünger’s natal sun sign and degree

In light of Jünger’s astrological inclinations and in furtherance of my own interest in astrological degree interpretation, the below is his natal chart Sun sign degree as interpreted by Carelli12:

8-9 deg Aries

The native has such faith in himself as to border on heedlessness, but will be assisted in danger by that cool-bloodedness which usually is the mark of true courage. Too proud to serve, he can fulfill himself as a leader or a cultist of the free arts; he is hardly a bearable subordinate, as his lack of modesty will let his inborn pride drift into conceit, haughtiness and misplaced touchiness.

Yet his never-falling, positive sense of reality always will lead him back to the right path if vanity has led him astray, and will enable him to show it to anyone willing to follow him.

Luckier than he deserves, he has a noble sense of friendship, which he feels strongly. He is on the other hand a dangerous foe.

All human activities based on the written or spoken word—political and forensic rhetoric, philosophy, writing-are congenial to him. He speaks well, even too well, and is bent on listening to himself rather than to others.

All of this is quite accurate. I think I may start presenting natal sun degrees in more figures I cover in future posts, along with my rules to cover a person’s physiognomy.

The weakness of Jünger’s conservatism

The problem of Jünger’s conservatism is that in a clash between technological “progress” and the human spirit the former always wins out against the latter in this world. “I harbored the suspicion that this world is modeled on the perfidious prototype of the charnel house [i.e. place of death]”, echoing gnostic thought. The gulf between modern views and the esoteric, mystical, aristocratic and honor-based views he expresses throughout his journals is monumental, a colossal void which grows even wider as time goes on. This is because the egalitarian ratchet effect increasingly pushes down anything that is superior to the lowest common denominator, and as part of that effect the history of the white Christian west is gradually eroded and destroyed. On January 17, 2024 Germany even removed his monument to the 200,000 German civilian dead at Dresden, firebombed in a monumental war crime for no military benefit, ironically protested against by the Russians. I wonder what Jünger would think of the current era with gay marriage, transsexualism, mass-censorship and increasing leftist totalitarianism and elite-enforced third world mass-migration into Europe and North America. He died in 1998 before this stuff really intensified.

According to Julius Evola, “Jünger…should be numbered among those individuals who first subscribed to 'Conservative Revolutionary' ideas but were later, in a way, traumatized by the National Socialist experience, to the point of being led to embrace the kind of sluggishly liberal and humanistic ideas which conformed to the dominant attempt 'to democratically reform' their country; individuals who have proven incapable of distinguishing the positive side of past ideas from the negative, and of remaining true to the former. Alas, this incapability to discern is, in a way, typical of contemporary Germany (the land of the 'economic miracle')."

At one (and only one) point in his journals Jünger noted that Hitler was attempting to transvalue the egalitarian, Christian values of the West back into Roman aristocratic, Darwinian will-to-power values, reflecting historian Tom Holland’s comments on the topic, explaining why his actions were so brutal:

“The situation could be described as a paradox: the warrior caste certainly wants to support war but in its archaic form. Nowadays it is waged by technicians. This is an area that includes the attacks of the new rulers against the ancient concept of military honor and the remnants of chivalry. When I studied the documents, I was often astonished by Kniebolo’s intransigence in minor differences (to put it diplomatically), for example, in the dispute over the heads of a handful of innocent people. We will never grasp this if we cannot see through his desire to destroy the nomos [law, customs], which guides him infallibly. This can be expressed impartially: He wants to create a new standard. And because there is so much about this new Reich that is medieval, it involves a steep decline.”

The transformation of society’s core values cannot be accomplished easily; there are huge numbers of people welded to the existing values and they will react with maximum resistance at any attempted to transvalue them. Hitler’s attempted solution was to murder those who resisted his imposition of the new aristocratic, hierarchical warrior values, and the shocking example those murders would set would serve to impose and solidify those new values onto the population. One might expect that once those new values were firmly accepted by the population that the extreme level of brutality would have been drastically reduced and even seen in a positive light, but who knows. As Holland states in the above link, “It is the incomplete revolutions which are remembered; the fate of those whose triumph [such as Christianity] is to be taken for granted.”

Regardless, while I have argued that a transvaluation of values away from pure egalitarianism is critical for humanity’s survival, I would like to see a balance between egalitarianism and inegalitarianism, not a total value inversion to the other polarity. Whatever specific form that might take is hard to know at this time.

Concluding thoughts

Thomas Friese, who translated Jünger’s “The Adventurous Heart”, had an interview where spoke about the core of Jünger’s difficult, disjointed writing style. To Friese, Jünger’s style was intentionally selected to help the reader learn to think for himself:

Thomas Friese: The main difficulty is following his often seemingly disjointed trains of thought. Naturally they are not disjointed, merely connected at a hidden level. To borrow his own description, they are like archipelagos, which form organic wholes, though it is not immediately apparent how the islands above the surface (the sentences) are connected. The reader, and even more the translator, must make the leaps themselves—this makes it more interesting, more involving. A related challenge with Jünger is maintaining his deliberate ambiguities or multiple meanings, without also giving them away, making them easier for the reader to understand than he intended. Jünger wants his readers to think for themselves. The same applies to the underwater connections between the islands—the translation should not try to explain the meaning; that is the reader’s task….

But although there is much in his thought that academia could engage with and society benefit from, its main audience is the individual; it seeks not to improve the world in general, which Jünger saw as a vanity, but to help the individual discover and develop himself—and thereby gain a position to help others do the same for themselves.

I think Jünger has succeeded at this in his war journals. It forces the reader to pay attention and to draw one’s own connections and conclusions. The world would be a better place with more free thinkers, and regardless of one’s politics this book could play a small role in encouraging its spread.

Thanks for reading.

Per Thomas Friese: “I’m glad you put the question in a current context—because there are two Jüngers that can be spoken of, even if the second grew out of the first, its developmental prerequisite. The second, the mature author, is the “current” Jünger, the man who gradually evolved into an anarch, starting more or less with this book, after leaving behind early experiments in the world of action and politics. I find the first interesting only to the degree that it helps explain the second. Let’s not forget: his first phase covered from 22 to about 42 years of age, 9 works or so—the second from 42 to 102, with 47 or 48 works! By the way, only 11 of these 59 works have ever been translated into English—not the case for French, Italian, or Spanish, which are more or less complete. Odd, no?”

Various excerpts of the last journal can be found online; for example, here are the entries pertaining to Hitler and Mussolini’s deaths.

This passage by Guido Giacomo Preparata in his “Empire and State” offers interesting insight into Junger’s early philosophy:

Junger’s point of departure in the 1920s is the standard Fascist one, namely the languorous yearning for the ancient “chivalry” and its knights, all creatures of a heroic and magical world, which are found to be deplorably deprived of breathing room in the atmosphere of mobilized masses and “technique". Very much bound to the mystique of “Blood and Soil,” Junger was, clearly, enamored of his national cradle. And having passionately fought in the Great War, he was also keenly aware of and profoundly perturbed by the unrelenting siege the Universalist spirit had been laying to his homeland.

For young pro-Fascist nationalists like him, “the supranational power,” - i.e. Jewry, Free-Masonry, High-Finance, and the “Church’s pursuit of power for the mere sake of power, which is customarily referred to as Jesuitism” - had coalesced into a conspiratorial nebula organically hostile to the aboriginal “will to fashion a community through blood-ties,” which is nationhood. “Nations,” wrote Junger, “are cores of organic bonds of a higher substance; an internationalist aggregation, on the other hand, is merely an instrumental abstraction which is concocted, behind the scenes, by an American brain.”

To him, when the time for settling scores would have come and native blood would have been given thereby occasion “to speak,” the unreal constructs of these “internationalist” conceptualizations would have collapsed like houses of cards. Interestingly, seeming to fear her most, young Junger stung the Church with relish (he would convert to Catholicism two years before his death, at the age of 101), and, again, like Borgese and Evola, wished her ill with yet another Neoconservative/Ghibelline curse.

Junger’s journals mention on multiple occasions the intentional extermination of the Jews, first via mass shooting and then via gas chambers, told to him by high ranking German officials and dutifully written down. Just two examples, one the December 31, 1942 entry: “On that note General Muller told about the monstrous atrocities perpetrated by the Security Service after entering Kiev. Trains were again mentioned that carried Jews into poison gas tunnels. Those are rumors, and I note them as such, but extermination is certainly occurring on a large scale.” And October 16, 1943 entry: “At the same time, new deported Jews pour in from the occupied countries. To dispose of these people, crematoria have been built not too far from the ghettoes. They take the victims there in vehicles that are supposed to be an invention of Chief Nihilist Heydrich. The exhaust fumes are piped into the interior so that they become death chambers.”

Or see: “I have to reach a plane from which I can view things the way a doctor examines patients, as if these were creatures like fish in a coral reef or insects on a meadow. It’s especially obvious that these things apply to the lower ranks. My disgust still betrays weakness and too great an identification with the [Darwinian struggle for existence]. We have to see through the logic of violence and beware of euphemism in the style of Millet or Renan. We also have to guard against the disgraceful role of those citizens who moralize about people who have made terrible bargains while looking down from the safety of their own roofs. Anyone not swallowed up by the conflict should thank God, but that does not give him license to judge.”

Although Jünger does have one piercing throwaway comment, June 8 1944: “It seems that money has the subtlest feelers and when bankers assess the situation, they do so more meticulously and with greater precision than generals.”

Also from here:

As for Hitler, that’s how it was. It was not a week after On the Marble Cliffs came out in the bookshops that the Reichsleiter of Hanover, a certain Bouhler, complained in Berlin that he thought the book incited a conspiracy. Hitler, who was an admirer of my World War I diaries, ruled that they should leave me alone. On more than one occasion he had made signs of friendship and expressed interest in me. But I did not let myself be flattered by those offers. It would have been too easy to exploit them for personal gain. It would not have taken much to do as Goering did.

Although the details are murky; he may have been murdered by the Nazis as revenge against Jünger for his spiritual support of the July 20 plot.

And, facing the prospect of death at the intense Allied aerial bombardments in 1945 he wrote, “We are approaching the innermost vortex of the maelstorm, almost certain death…my baggage, my treasures, I shall have to leave behind without regret. After all, they are valuable only to the extent that they have an intrinsic connection to the other side.”

Indeed, becoming an “anarch” is difficult to emulate. There is a quote which I am paraphrasing which comes to mind: “change a person’s actions and the mind will follow.” Somewhat akin to Upton Sinclair’s, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on him not understanding it!” People want to see themselves as morally correct; if they are forced to behave contrary to their beliefs, their beliefs will eventually “update” themselves to correspond to their actions. Jünger was in a unique situation: hailed as a war hero and literary figure, he was allowed to exist in a space where he did not have to violate his internal beliefs. This is hardly a solution for many. Still…

I agree. I don't care about changing society, I am more interested in ways for individuals to improve mental, physical and spiritual strength. Enough individuals make such change, then society will.

Excellent piece, a wonderful contribution to Jünger studies.