A Philosophy of Decay: Emil Cioran and the Boundaries of Pessimistic Thought

Reflections on the Paradox of Life and Death

This essay explores Emil Cioran’s philosophy, revealing how his reflections on pessimism, suffering, and the human condition offer a radical form of freedom. Through his life and aphorisms Cioran challenges conventional views of hope, progress, and meaning where, without the burden of progress or idealized outcomes, life becomes more open to unexpected joys and surprises. His thoughts serves as a guide to live without the constraints of conventional optimism, embracing life in its complexity and unpredictability.

This is a post about an extreme philosophical pessimist: Emil Cioran.

Cioran is known as one of the great writers of aphorisms (i.e. short, fragmented ideas communicated within a few paragraphs) who became famous for his A Short History of Decay (1949). I felt reluctant to cover him because his writing leaves a sour taste in the mouth, a claustrophobic dread, as a brutally pessimist author who basically used his writing as a therapy tool so he wouldn’t kill himself or go mad. “A book,” said Cioran, “is a suicide postponed.” Indeed, Cioran believed that by coping directly with the horrors of this world it would strip away illusion and perhaps make life worth living. “Only optimists commit suicide, optimists who no longer succeed at being optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why would they have any to die?”

Many authors use writing as a coping tool; I do as well. But my outlook is not as relentlessly bleak as Cioran’s, even though it’s bleaker than most other Substacks. The intent here is not to lean into the pessimism as much as he did; rather, the question is where can one find hope and meaning in a world of intensifying neoliberal feudalism and ubiquitous nihilism? (And I do see some, also here.)

So why did I want to cover Cioran? Three reasons. First, to highlight the many themes he covers which overlap with this Substack; second, because I enjoy reviewing strange figures who march to the beat of their own drum - it is by following our intuition (within reason, in a measured capacity) that we can become who we are really meant to be; and third, as a limit to how far one can push their pessimism. I don’t want to be as pessimistic as Cioran; it is too much. So is the approach of the infamous “Nothing Good Has Ever Happened”

for that matter - I feel like I should perhaps dedicate this post to him, lol.1 An element of “maybe” from the Chinese farmer story is a healthier approach, even though pessimism is a nice baseline - I would rather be pleasantly surprised to the upside than to the downside.Cioran’s background

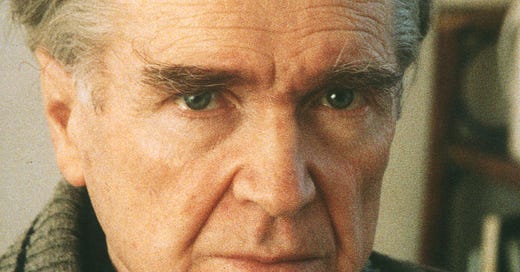

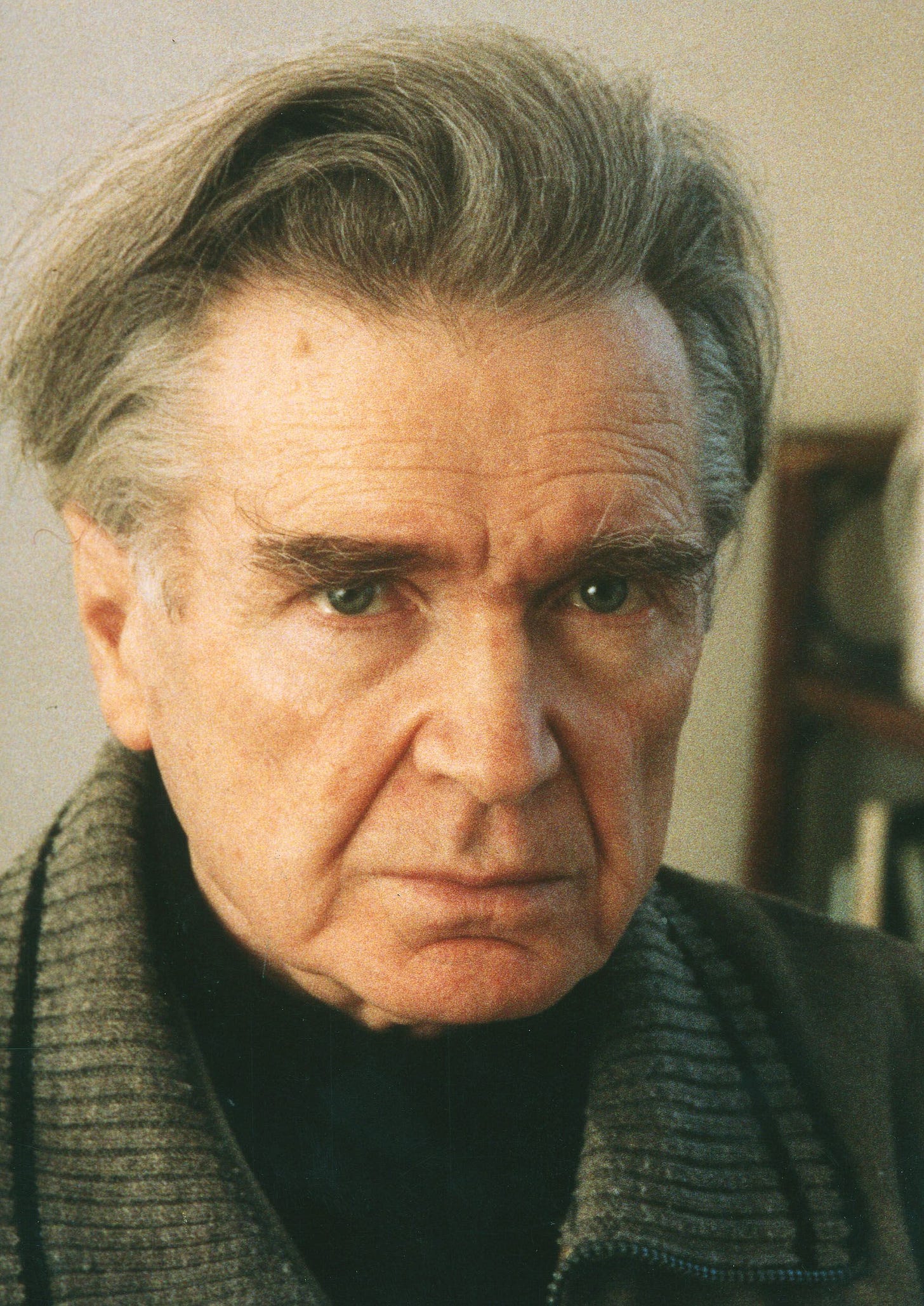

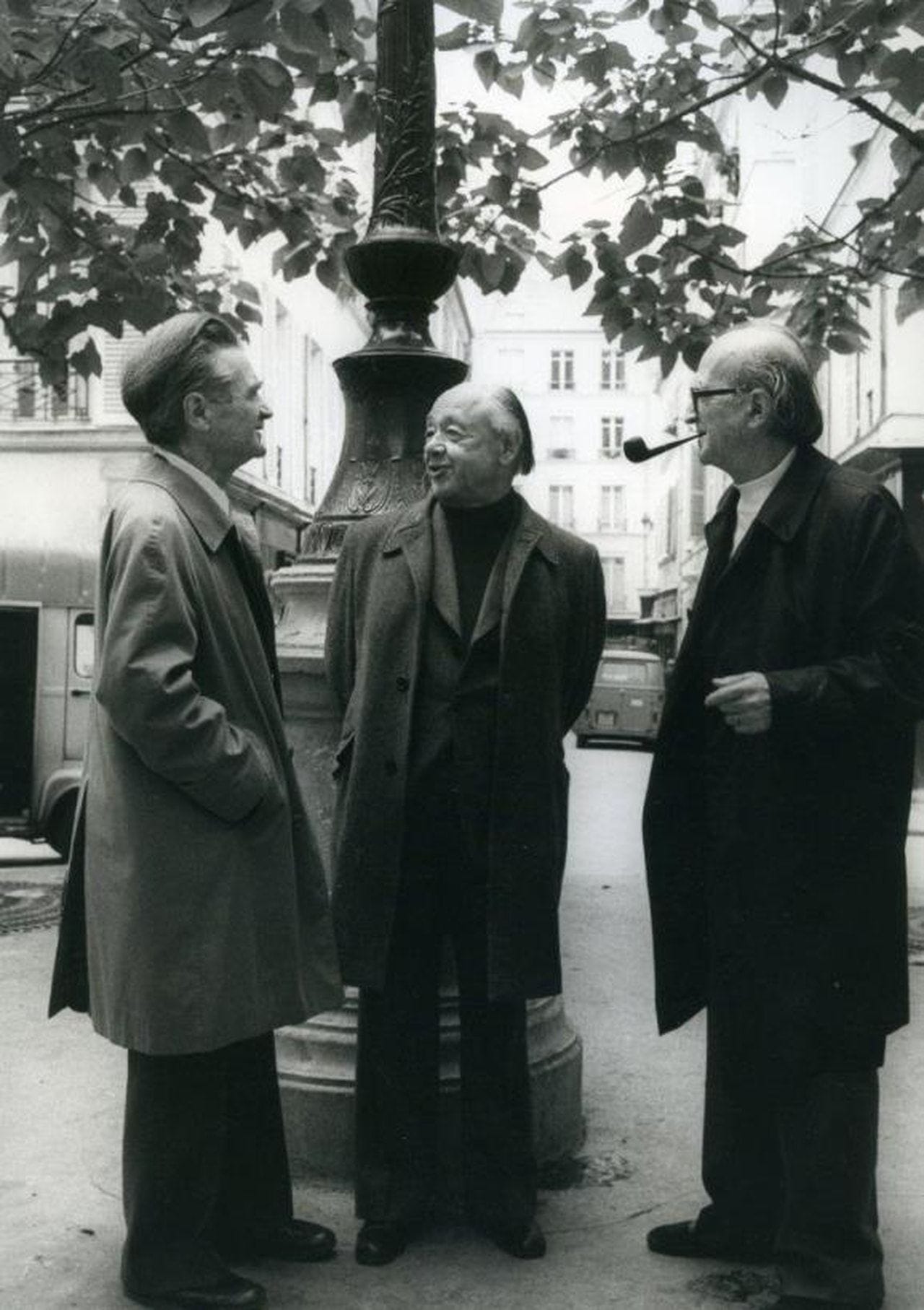

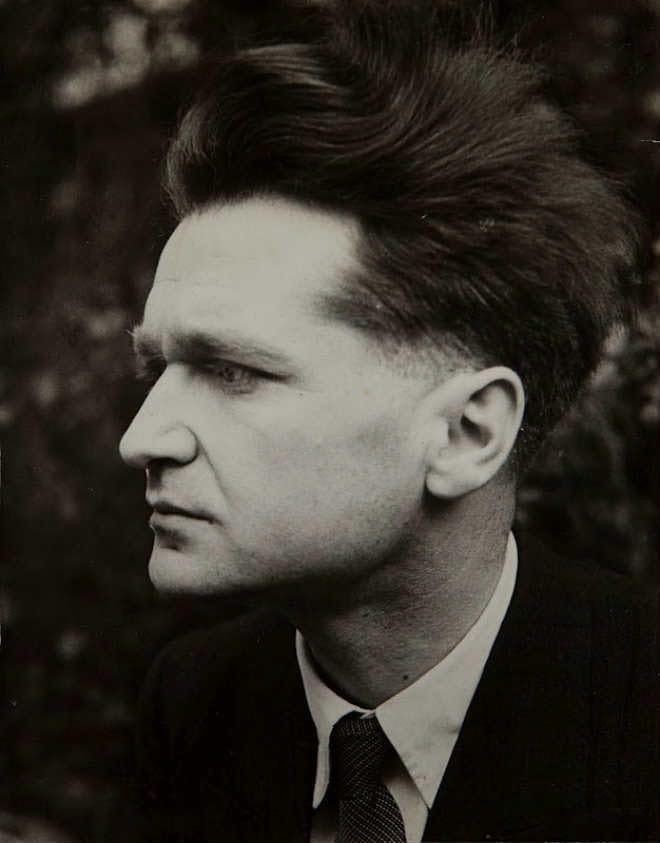

Cioran was a Romanian born in 1915 to a Greek Orthodox priest father and who supported the far right during the rise of Fascism, including Hitler and the Iron Guard.2 He moved to France, refused to be drafted by Romania to fight Russia in the Soviet Union, and became somewhat disillusioned with politics after the Axis lost. He lived in Paris for the next fifty-some years where he refused to work a “real” job, wrote a couple dozen pessimistic books and then died of Alheizmer’s in 1995 at 84 years old (after planning to kill himself as his mental facilities declined but he waited too long3). He was the friend of other famous writers such as Eugène Ionesco and Mircea Eliade. He said nothing good comes from getting old, though: “One doesn’t become better on the moral plane with old age. Nor wiser. Contrary to what people think. One gains nothing in getting old. But as one is more tired, one gives the impression of wisdom….There is no progress in life. There are small changes.” He was an anti-natalist and had no children, something I see as foolish and decadent.

His break from the mainstream perspective began from the unrelenting insomnia he suffered as a teenager.4 He wrote his famous A Short History of Decay, which included dozens of aphorisms about decay in all its forms, by forcing himself to learn to write French in his late 20s and 30s. It was a very difficult process which he ended up re-writing three times. Cioran described the process of learning French as "the most difficult task of my life", comparing it to "putting on a straitjacket".

Overlapping themes

What are the overlapping themes between Cioran and this Substack?

Cioran was a 20th century gnostic according to professor Costica Bradatan:

In his books, Cioran never stopped berating the gods, except, we might say, for the god of failure, the demiurge of the Gnostics. There is something distinctly Gnostic about Cioran’s anti-cosmic philosophy and the manner of his thinking. Gnostic insights, images, and metaphors permeate his work, as scholars of Gnosticism have noticed. A Short History of Decay, The Temptation to Exist, and The New Gods, writes Jacques Lacarrière, are “texts which match the loftiest flashes of Gnostic thought.” Just like the Gnostics of old, Cioran sees creation as the result of a divine failure; human history and civilization are for him nothing but “the work of the devil,” the demiurge’s other name. In A Short History of Decay, he deems the God of this world “incompetent.” “Of all that was attempted on this side of nothingness,” he wonders, “is there anything more pathetic than this world, except for the idea which conceived it?” The French title of one of his most influential books, which in English has been published as The New Gods, is telling — Le Mauvais démiurge (1969): “the evil demiurge.” Here, with unconcealed sympathy, Cioran calls the Gnostics “fanatics of the divine nothingness” and praises them for having “grasped so well the essence of the fallen world.”

He had a strong interest in esotericism and mysticism. He disliked exoteric religion and considered becoming a Buddhist before rejecting it - “What attracted me to Buddhism is the statement that everything is illusion, that nothing is real. It’s perhaps the negative aspect of Buddhism that I liked, the statements on life that it makes.”

He believed deeply in philosophical pessimism, tying in nicely with gnosticism and esotericism. Cioran was heavily influenced by Nietzsche in his youth (h/t

) although he later came to pity him5; he loved Schopenhauer and despised Heidegger.6 I discussed philosophical pessimism in depth here.Cioran was unique and stood out from the crowd - he was a Jungerian-esque anarch, keenly following his intuition — where are these figures today? Has the ubiquitous conformity brought about by mass media and high technology simply killed it? Or do they still exist, lurking in the shadows but not generating the public’s attention of yesteryear?

He also had strongly anti-democratic leanings which did not dissipate later in life and he distrusted the notions of so-called “progress”.

Cioran refused to work as a wagecuck where he would have been enslaved: he would rather be dignified and poor, much like Diogenes of Sinope.

Cioran would do anything, except take up a job. Doing so would have been the failure of his life. “For me,” an older Cioran remembers, “the main thing was to safeguard my freedom. Had I ever accepted to take up an office job, to make a living, I would have failed.” In order not to fail, then, he chose a path most would consider failure embodied, but Cioran knew that failure is always a complicated affair. “I avoided at any price the humiliation of a career […] I preferred to live like a parasite [rather] than to destroy myself by keeping a job.” As all great idlers know, there is perfection in inaction: Cioran was not only aware of it, but he also cultivated it all his life. When an interviewer asked him about his working routines, Cioran answered: “Most of the time I don’t do anything. I am the idlest man in Paris […] the only one who does less than I do is a whore without clients.”

He was also critical of success, echoing thoughts offered on this Substack.7 “There is something of the charlatan in anyone who triumphs in any realm whatever,” [Cioran] wrote. One has to sell out to the powers that be, to squelch your independent thought, to ally with an existing power center (as

states) to have mainstream success at anything. Cioran turned down most awards, refused almost all interviews and led a quiet and poor life. He also studied the concept of failure thoroughly. Per the Los Angeles Review of Books, “[Cioran] knew how to appreciate a worthwhile case of failure, how to observe its unfolding and savor its complexity. For failure is irreducibly unique: successful people always manage to look the same, but those who fail fail so differently. Each case of failure has a physiognomy and a beauty all of its own, and it takes a subtle connoisseur like Cioran to tell a seemingly banal but in fact great failure from a noisy yet mediocre one.”8 And: “[Cioran] can measure, for example, the depth of someone’s inner life by the way they approach failure: “This is how we recognize the man who has tendencies toward an inner quest: he will set failure above any success.” How so? Because failure, Cioran thinks, “always essential, reveals us to ourselves, permits us to see ourselves as God sees us, whereas success distances us from what is most inward in ourselves and indeed in everything.” Show me how you deal with failure, and I will tell you more about yourself. Only “in failure, in the greatness of a catastrophe, can you know someone.” (As an aside, has a nice post on failing at standup and another one on the lessons he learned from the experience.)He thought that one should only be writing if compelled. In other words, to write for writing’s sake or for attention will not achieve the desired effect: “In my opinion, a book should be written without thinking of others. You shouldn’t write for anyone, only for yourself….Everything I’ve written, I wrote to escape a sense of oppression, suffocation. It wasn’t from inspiration, as they say. It was a sort of getting free, to be able to breathe.” He also stressed the importance of writing in accordance with temperament: “A writer mustn’t know things in depth. If he speaks of something, he shouldn’t know everything about it, only the things that go with his temperament. He should not be objective. One can go into depth with a subject, but in a certain direction, not trying to cover the whole thing. For a writer the university is death.” (This is relevant in an age where everyone can write, but very few are well read per

here).Unlike Nietzsche, who believed only the acceptance of contradictory ideas could result in a higher-level synthesis and come closer to truth, Cioran believed that it was not man’s responsibility to synthesize such information but rather to articulate what we feel in the moment, regardless of whether we may think or feel something else later. Contradiction was simply irrelevant:

When they read a book of aphorisms, they say, "Oh, look what this fellow said ten pages back, now he's saying the contrary. He's not serious." Me, I can put two aphorisms that are contradictory right next to each other. Aphorisms are also momentary truths. They're not decrees. And I could tell you in nearly every case why I wrote this or that phrase, and when. It's always set in motion by an encounter, an incident, a fit of temper, but they all have a cause. It's not at all gratuitous.

As Bradatan explained, “With [Cioran], self-contradiction is not even a weakness, but the sign a mind is alive. For writing, he believed, is not about being consistent, nor about persuasion or keeping a readership entertained; writing is not even about literature. For Cioran, just like Montaigne several centuries earlier, writing has a distinctive performative function: you write not to produce some body of text, but to act upon yourself; to bring yourself together after a personal disaster or to pull yourself out of a bad depression; to come to terms with a deadly disease or to mourn the loss of a close friend.”

Select aphorisms

Below are a handpicked number of select aphorisms (or parts of aphorisms) that stood out to me. I whittled it down to ten (the last being my favorite). If they catch your interest, A Short History of Decay is available for free online here.

Fanaticism vs Skepticism (“Genealogy of Fanaticism”)

….Once man loses his faculty of indifference he becomes a potential murderer; once he transforms his idea into a god the consequences are incalculable. We kill only in the name of a god or of his counterfeits: the excesses provoked by the goddess Reason, by the concept of nation, class, or race are akin to those of the Inquisition or of the Reformation. The ages of fervor abound in bloody exploits: a Saint Teresa could only be the contemporary of the auto-da-fé, a Luther of the repression of the Peasants’ Revolt. In every mystic outburst, the moans of victims parallel the moans of ecstasy. . . . Scaffolds, dungeons, jails flourish only in the shadow of a faith—of that need to believe which has infested the mind forever. The devil pales beside the man who owns a truth, his truth. We are unfair to a Nero, a Tiberius: it was not they who invented the concept heretic: they were only degenerate dreamers who happened to be entertained by massacres. The real criminals are men who establish an orthodoxy on the religious or political level, men who distinguish between the faithful and the schismatic.

What is the Fall but the pursuit of a truth and the assurance you have found it, the passion for a dogma, domicile within a dogma? The result is fanaticism—fundamental defect which gives man the craving for effectiveness, for prophecy, for terror—a lyrical leprosy by which he contaminates souls, subdues them, crushes or exalts them. . . . Only the skeptics (or idlers or aesthetes) escape, because they propose nothing, because they—humanity’s true benefactors—undermine fanaticism’s purposes, analyze its frenzy. I feel safer with a Pyrrho than with a Saint Paul, for a jesting wisdom is gentler than an unbridled sanctity. In the fervent mind you always find the camouflaged beast of prey; no protection is adequate against the claws of a prophet. . . . Once he raises his voice, whether in the name of heaven, of the city, or some other excuse, away with you: satyr of your solitude, he will not forgive your living on the wrong side of his truths and his transports; he wants you to share his hysteria, his fullness, he wants to impose it on you, and thereby to disfigure you. A human being possessed by a belief and not eager to pass it on to others is a phenomenon alien to the earth, where our mania for salvation makes life unbreathable. Look around you: everywhere, specters preaching; each institution translates a mission; city halls have their absolute, even as the temples —officialdom, with its rules—a metaphysics designed for monkeys. . . Everyone trying to remedy everyone’s life: even beggars, even the incurable aspire to it: the sidewalks and hospitals of the world overflow with reformers. The longing to become a source of events affects each man like a mental disorder or a desired malediction. Society—an inferno of saviors! What Diogenes was looking for with his lantern was an indifferent man. . .

It is enough for me to hear someone talk sincerely about ideals, about the future, about philosophy, to hear him say “we” with a certain inflection of assurance, to hear him invoke “others” and regard himself as their interpreter - for me to consider him my enemy. I see in him a tyrant manqué an approximate executioner, quite as detestable as the first-rate tyrants, the first-rate executioners. Every faith practices some form of terror, all the more dreadful when the “pure” are its agents.

To get over fear of death, one must become acquainted with it (“Variations on Death”)

And it is death, the most intimate dimension of all the living, which separates humanity into two orders so irreducible, so removed from each other, that there is more distance between them than between a vulture and a mole, a star and a starfish. The abyss of two incommunicable worlds opens between the man who has the sentiment of death and the man who does not; yet both die; but one is unaware of his death, the other knows- one dies only for a moment, the other unceasingly. . . . Their common condition locates them precisely at each other’s antipodes, at the two extremities and within one and the same definition; irreconcilable, they suffer the same fate. . . . One lives as if he were eternal; the other thinks continually of his eternity and denies it in each thought.

The man who has not given himself up to the pleasures of anguish, who has not savored in his mind the dangers of his own extinction nor relished such cruel and sweet annihilations, will never be cured of the obsession with death: he will be tormented by it, for he will have resisted it; while the man who, habituated to a discipline of horror, and meditating upon his own carrion, has deliberately reduced himself to ashes—that man will look toward death’s past, and he himself will be merely a resurrected being who can no longer live. His “method” will have cured him of both life and death.

Salvation as death, the end of being. (“Annihilation by Deliverance”)

A doctrine of salvation has meaning only if we start from the equation “existence equals suffering.” It is neither a sudden realization, nor a series of reasonings which lead us to this equation, but the unconscious elaboration of our every moment, the contribution of all our experiences, minute or crucial. When we carry germs of disappointments and a kind of thirst to see them develop, the desire that the world should undermine our hopes at each step multiplies the voluptuous verifications of the disease. The arguments come later; the doctrine is constructed: there still remains only the danger of “wisdom.” But, suppose we do not want to be free of suffering nor to conquer our contradictions and conflicts— what if we prefer the nuances of the incomplete and an affective dialectic to the evenness of a sublime impasse? Salvation ends everything; and ends us. Who, once saved, dares still call himself alive? We really live only by the refusal to be delivered from suffering and by a kind of religious temptation of irreligiosity. Salvation haunts only assassins and saints, those who have killed or transcended the creature; the rest wallow—dead drunk—in imperfection. . . .

The mistake of every doctrine of deliverance is to suppress poetry, climate of the incomplete. The poet would betray himself if he aspired to be saved: salvation is the death of song, the negation of art and of the mind. How to feel integral with a conclusion? We can refine, we can farm our sufferings, but by what means can we free ourselves from them without suspending ourselves? Docile to malediction, we exist only insofar as we suffer. A soul enlarges and perishes only by as much insupportable as it assumes.

On metaphysical rebellion against reality itself (“The Model Traitor”)

Since life can be fulfilled only within individuation—that last bastion of solitude —each being is necessary alone by the fact that he is an individual. Yet all individuals are not alone in the same way nor with the same intensity: each occupies a different rank in the hierarchy of solitude; at one extreme stands the traitor: he is an individual to the point of exasperation. In this sense, Judas is the loneliest being in the history of Christianity, but not in the history of solitude. He betrayed only a god; he knew what he betrayed; he betrayed someone, as so many others betray something: a country or other more or less collective pretexts. The betrayal which focuses on a specific object, even if it involves dishonor or death, is not at all mysterious: we always have the image of what we want to destroy; guilt is clear, whether admitted or denied. The others cast you out, and you resign yourself to the cell or the guillotine. . . .

But there exists a much more complex modality of betrayal, without immediate reference, without relation to an object or a person. Thus: to abandon everything without knowing what this everything represents; to isolate yourself from your milieu; to reject—by a metaphysical divorce—the substance which has molded you, which surrounds you, and which carries you.

Who, and by what defiance, can challenge existence with impunity? Who, and by what efforts, can achieve a liquidation of the very principle of his own breath? Yet the will to undermine the foundations of all that exists produces a craving for negative effectiveness, powerful and ineffable as a whiff of remorse corrupting the young vitality of a hope. . .

When you have betrayed being you bear with you only a vague discomfort; there is no image sustaining the object which provokes the sensation of infamy. No one casts the first stone; you are a respectable citizen as before; you enjoy the honors of the city, the consideration of your kind; the laws protect you; you are as estimable as anyone else-—and yet no one sees that you are living your funeral in advance and that your death can add nothing to your irremediably established condition. This is because the traitor to existence is accountable only to himself. Who else can ask him for an accounting? If you denounce neither a man nor an institution, you run no risk; no law protects Reality, but all of them punish you for the merest prejudice against its appearances. You are entitled to sap Being itself, but no human being; you may legally demolish the foundations of all that is, but prison or death awaits your least infringement of individual powers. Nothing protects Existence: there is no case against metaphysical traitors, against the Buddhas who reject salvation, for we judge them traitors only to their own lives. Yet of all malefactors, these are the most harmful: they do not attack the fruit, but the very sap of the universe. Their punishment? They alone know what it is. . .

It may be that in every traitor there is a thirst for opprobrium, and that his choice of betrayal depends on the degree of solitude he aspires to. Who has not experienced the desire to perpetrate an incomparable crime which would exclude him from the human race? Who has not coveted ignominy in order to sever for good the links which attach him to others, to suffer a condemnation without appeal and thereby to reach the peace of the abyss? And when we break with the universe, is it not for the calm of an unpardonable crime? A Judas with the soul of a Buddha—what a model for a coming and concluding humanity!

A flourishing mankind paradoxically only comes from turning one’s back on the universal (“The Flower of Fixed Ideas”)

So long as man is protected by madness, he functions and flourishes; but when he frees himself from the fruitful tyranny of fixed ideas, he is lost, ruined. He begins to accept everything, to wrap not only minor abuses in his tolerance, but crimes and monstrosities, vices and aberrations: everything is worth the same to him. His indulgence, self-destroying as it is, extends to all the guilty, to the victims and the executioners; he takes all sides, because he espouses all opinions; gelatinous, contaminated by infinity, he has lost his “character,” lacking any point of reference, any obsession. The universal view melts things into a blur, and the man who still makes them out, being neither their friend nor their enemy, bears in himself a wax heart which indiscriminately takes the form of objects and beings. His pity is addressed to . . . existence, and his charity is that of doubt and not that of love; a skeptical charity, consequence of knowledge, which excuses all anomalies. But the man who takes sides, who lives in the folly of decision and choice, is never charitable; incapable of comprehending all points of view, confined in the horizon of his desires and his principles, he plunges into a hypnosis of the finite. This is because creatures flourish only by turning their backs on the universal . . . To be something—unconditional— is always a form of madness from which life—flower of fixed idea—frees itself only to fade.

We see a man’s last words as the summation of his life (“History and Language”)

When, at the dying man’s bedside, his nearest and dearest bend over his stammerings, it is not so much to decipher in them some last wish, but rather to gather up a good phrase which they can quote later on, in order to honor his memory. If the Roman historians never fail to describe the agony of their emperors, it is in order to place within them a sentence or an exclamation which the latter uttered or were supposed to have uttered. This is true for all deathbeds, even the most ordinary. That life signifies nothing, everyone knows or suspects; let it at least be saved by a turn of phrase! A sentence at the corners of their life —that is about all we ask of the great—and of the small. If they fail this requirement, this obligation, they are lost forever; for we forgive everything, down to crimes, on condition they are exquisitely glossed—and glossed over. This is the absolution man grants history as a whole, when no other criterion is seen to be operative and valid, and when he himself, recapitulating the general inanity, finds no other dignity than that of a litterateur of failure and an aesthete of bloodshed.

In this world, where sufferings are merged and blurred, only the Formula prevails.

Introspection as the mark of a society’s death (“Advantages of Debility”)

…“Inner life” is the prerogative of the delicate, those tremulous wretches subject to an epilepsy with neither froth nor falling: the biologically sound being scorns “depth,” is incapable of it, sees in it a suspect dimension which jeopardizes the spontaneity of his actions. Nor is he mistaken: with the retreat into the self begins the individual’s drama—his glory and his decline; isolated from the anonymous flux, from the utilitarian trickle of life, he frees himself from objective goals. A civilization is “affected” when its delicate members set the tone for it; but thanks to them, it has definitively triumphed over nature—and collapses. An extreme example of refinement unites in himself the exalté and the sophist: he no longer adheres to his impulses, cultivates without crediting them; this is the omniscient debility of twilight ages, prefiguration of man’s eclipse. The delicate allow us to glimpse the moment when janitors will be tormented by aesthetes' scruples; when farmers, bent double by doubts, will no longer have the vigor to guide the plow; when every human being, gnawed by lucidity and drained of instincts, will be wiped out without the strength to regret the flourishing darkness of their illusions…

Psychology as having killed the hero (“Faces of Decadence”)

Nothing monumental has ever emerged from dialogue, nothing explosive, nothing “great.”….The clear-sighted person who understands himself, explains himself, justifies himself, and dominates his actions will never make a memorable gesture. Psychology is the hero’s grave. The millennia of religion and reasoning have weakened muscles, decisions, and the impulse of risk. How keep from scorning the enterprises of glory? Every act over which the mind’s luminous malediction fails to preside represents a vestige of ancestral stupidity. Ideologies were invented only to give a luster to the leftover barbarism which has survived down through the ages, to cover up the murderous tendencies common to all men. Today we kill in the name of something; we no longer dare do so spontaneously; so that the very executioners must invoke motives, and, heroism being obsolete, the man who is tempted by it solves a problem more than he performs a sacrifice. Abstraction has insinuated itself into life—and into death; the “complexes” seize great and small alike. From the Iliad to psychopathology— there you have all of human history.

History confirms skepticism but only fanaticism makes for strong societies (“Views on Tolerance”)

Signs of life: cruelty, fanaticism, intolerance; sighs of decadence: amenity, understanding, indulgence. .. . So long as an institution is based on strong instincts, it admits neither enemies nor heretics: it massacres, burns, or imprisons them. Stakes, scaffolds, prisons! it is not wickedness which invented them, but conviction, any utter conviction. Once a belief is established the police will guarantee its “truth” sooner or later. Jesus—once he wanted to triumph among men—should have been able to foresee Torquemada, ineluctable consequence of Christianity translated into history. And if the Lamb failed to anticipate the torturer of the Cross, his future defender, then he deserves his nickname. By the Inquisition, the Church proved that it still possessed enormous vitality; similarly, the kings by their “royal will”. All authorities have their Bastille: the more powerful an institution, the less humane. The energy of a period is measured by the beings that suffer in it, and it is by the victims it provokes that a religious or political belief is affirmed, bestiality being the primal characteristic of any success in time. Heads fall where an idea prevails; it can prevail only at the expense of other ideas and of the heads which conceived or defended them.

History confirms skepticism; yet it is and lives only by trampling over it; no event rises out of doubt, but all considerations of events lead to it and justify it. Which is to say that tolerance—supreme good on earth—is at the same time the supreme evil. To admit all points of view, the most disparate beliefs, the most contradictory opinions, presupposes a general state of lassitude and sterility. Whence we arrive at this miracle: the adversaries coexist—but precisely because they can no longer be adversaries; opposing doctrines recognize each other’s merits because none has the vigor to assert itself. A religion dies when it tolerates truths which exclude it; and the god in whose name one no longer kills is dead indeed. An absolute perishes: a vague glow of earthly paradise appears, a fugitive gleam, for intolerance constitutes the law of human affairs. Collectivities are reinforced only under tyrannies, and disintegrate in a regime of clemency; then, in a burst of energy, they begin to strangle their liberties and to worship their jailers, crowned or commoners.

The periods of fear predominate over those of calm; man is much more vexed by the absence than by the profusion of events; thus History is the bloody product of his rejection of boredom.

And my favorite, the Felicity of Epigones:

Is there a pleasure more subtly ambiguous than to watch the ruin of a myth? What dilapidation of hearts in order to beget it, what excesses of intolerance in order to make it respected, what terror for those who do not assent to it, and what expense of hopes for those who watch it . . . expire! Intelligence flourishes only in the ages when beliefs wither, when their articles and their precepts slacken, when their rules collapse. Every period’s ending is the mind’s paradise, for the mind regains its play and its whims only within an organism in utter dissolution. The man who has the misfortune to belong to a period of creation and fecundity suffers its limitations and its ruts; slave of a unilateral vision, he is enclosed within a limited horizon. The most fertile moments in history were at the same time the most airless; they prevailed like a fatality, a blessing for the naive mind, mortal to an amateur of intellectual space. Freedom has scope only among the disabused and sterile epigones, among the intellects of belated epochs, epochs whose style is coming apart and is no longer inspired except by a certain ironic indulgence.

To belong to a church uncertain of its god—after once imposing that god by fire and sword—should be the ideal of every detached mind. When a myth languishes and turns diaphanous, and the institution which sustains it turns clement and tolerant, problems acquire a pleasant elasticity. The weak point of a faith, the diminished degree of its vigor set up a tender void in men’s souls and render them receptive, though without permitting them to be blind, yet, to the superstitions which lie in wait for the future they darken already. The mind is soothed only by those agonies of history which precede the insanity of every dawn.

This reminds me of a statement by the Jungian psychologist James Hollis in his Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life, where he states: “Wherever certainty is brandished so vehemently, it is generally in compensation for unconscious doubt, and therefore is dishonest. Our anxieties lead us to grasp at certainties. Certainties lead to dogma; dogma leads to rigidity; rigidity leads to idolatry; idolatry always banishes the mystery and thus leads to spiritual narrowing. To bear the anxiety of doubt is to be led to openness; openness leads to revelation; revelation leads to discovery; discovery leads to enlargement.”

Conclusion

Despite the darkness and despair of Cioran’s work, it’s a breath of fresh air when one gets sick enough with the bullshit of modern society - he pulls no punches and he writes for no one else. His insights are top notch and his writing strong. I was uncertain if I would continue reading his works after finishing A Short History of Decay because it was so downbeat, but a number of months later I returned to him with his The New Gods (1969) which deals with gnostic themes, which I enjoyed and will cover in a future post. Cioran’s work doesn’t offer the comforting illusion of progress or meaning, but that’s exactly what makes it liberating. The absence of expectation frees you from the weight of constant striving. I’m going to keep reading his other works, but sparingly, as a palette cleanser when my feeling of societal nonsense becomes too strong. There’s something freeing in accepting life as it is, and Cioran helps remind you of that in his uncompromising way.

Thanks for reading.

PS: While I have not enabled paid subscriptions at this time, I am going to try out crypto if you found my work helpful and would like to donate. Posts are and will remain free. This is an experiment and is subject to further changes:

Bitcoin: bc1qh6cdaagqwcmp7ctqt9gdj6y6xjr88a7pz7fgpg

Ethereum: 0x30DB893613D032cdcE3B4F6De86aF921A236a7C3

Monero: 43CX9B3nfmJcmrD624pTq86gNRFeEk2eMMWjWtMy59afX8Szrxt88VkXRw6ez3LKWXcLtZxWjGgrk9Kecv9xvqsvGJcGrVa

Will goes around Substack spamming this message to anyone who will listen, and many who don’t or won’t. I think he may have been suspended for spamming previously, which is a very hard thing to accomplish on Substack at this time. I think he may be trolling in part — his response to a Note about the Chinese farmer story was too over-the-top not to be.

From here: “A further glimpse into Cioran’s peculiar manner of political thinking, in a letter he sent to Mircea Eliade in 1935: “My formula for all things political,” he writes, “is the following: fight wholeheartedly for things in which you do not believe.” Not that such a confession brings much clarity to Cioran’s involvement, but it places his “ravings” within a certain psychological perspective. This split personality characterized the later Cioran, and it makes sense, for a philosopher who sees the world as a failure of grand proportions, to mock the cosmic order (and himself in the process) by pretending that there is some meaning where there is none. You know that everything is pointless, but by behaving as if it wasn’t, you manage to articulate your dissent and undermine the designs of the “evil demiurge.” And you do that with boundless irony and humor, which is rigorously meant to counter the divine farce. He who laughs last laughs hardest.”

Id. “In a sense, however, he had already left before he died. For the last several years he had suffered from Alzheimer’s and had been interned at the Broca Hospital in Paris. Fearing precisely such an ending, he had planned to commit suicide. Cioran and his longtime partner, Simone Boué, were to die together, like the Koestlers. But the disease was faster, the plan failed, and Cioran had to die the most humiliating of deaths, one that took several years to do its work.”

“But that was a precise period, about six or seven years, where my whole perspective on the world changed. I think it’s a very important problem. It happens like this: normally someone who goes to bed and sleeps all night, the next day he begins a new life almost. It’s not simply another day, it’s another life. And so, he can undertake things, he can express himself, he has a present, a future, and so on. But for someone who doesn’t sleep, from the time of going to bed at night to waking up in the morning it’s all continuous, there’s no interruption. Which means, there is no suppression of consciousness. It all turns around that. So, instead of starting a new life, at eight in the morning you’re like you were at eight the evening before. The nightmare continues uninterrupted in a way, and in the morning, start what? Since there’s no difference from the night before. That new life doesn’t exist. The whole day is a trial, it’s the continuity of the trial. While everyone rushes toward the future, you are outside. So, when that’s stretched out for months and years, it causes the sense of things, the conception of life, to be forcibly changed. You don’t see what future to look forward to, because you don’t have any future. And I really consider that the most terrible, most unsettling, in short the principal experience of my life. There’s also the fact that you are alone with yourself. In the middle of the night, everyone’s asleep, you are the only one who is awake. Right away I’m not a part of mankind, I live in another world. And it requires an extraordinary will to not succumb.”

From here: “What I consider his most authentic work is his letters, because in them he’s truthful, while in his other work he’s prisoner to his vision. In his letters one sees that he’s just a poor guy, that he’s ill, exactly the opposite of everything he claimed….It’s because that whole vision, of the will to power and all that, he imposed that grandiose vision on himself because he was a pitiful invalid. Its whole basis was false, nonexistent. His work is an unspeakable megalomania. When one reads the letters he wrote at the same time, one sees that he’s pathetic, it’s very touching, like a character out of Chekhov. I was attached to him in my youth, but not after. He’s a great writer, though, a great stylist.”

Id. “The German influence in France was disastrous on that whole level, I find. The French can’t say things simply anymore….it’s the influence of Heidegger, which was very big in France. For example, he’s speaking about death, he employs so complicated a language, to say very simple things, and I well understand how one could be tempted by that style. But the danger of philosophical style is that one loses complete contact with reality. Philosophical language leads to megalomania. One creates an artificial world where one is God. I was very proud being young and very pleased to know this jargon. But my stay in France totally cured me of that.”

i.e. see the second half of this post: “In a society hyper-focused on enforcing conformity via the Overton Window or risk being cast out, jumping from one fake meta-narrative to the next to keep the public entertained, only the Loser clique loser, the lowest of the low, the most socially awkward, the worst performer financially, the eternal outsider, can discern the truth of the state of society and dream of a course correct. It is, indeed, the only thing they are good at. This is because when other cliques achieve financial success or academic prominence or excel at sports - really any activity not associated with being a Loser - such success comes with strings attached that require one to compromise one’s views in order to retain their social status. Only the Loser, lacking any success at all, can afford to grasp and promote viewpoints that lack social status.”

One may also note that Carl Jung felt the same way about failure, where he wrote in an essay Aims of Psychotherapy: “The psychologist learns little or nothing from his successes. They mainly confirm him in his mistakes, while his failures, on the other hand, are priceless experiences in that they not only open up the way to a deeper truth, but force him to change his views and methods.”

Tolstoy posited a similar analogy in his novel Anna Karenina : "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

"andyet no one sees that you are living your funeral in advance and that your death can add nothing to your irremediably established condition"

I call them cognitive zombies. Ian McGilchrist and others touched on this subject.

https://robc137.substack.com/p/alphabet-vs-the-goddess

And this is the basis of what they planned COVID to do.

https://robc137.substack.com/p/covid

"Cioran believed that by coping directly with the horrors of this world it would strip away illusion and perhaps make life worth living."

Right now it's 2025 and murderers in white coats are still using toxic Remdesevir in hospitals. Kennedy does nothing to stop it. I never wanted to be a pessimist but until people wake the frak up and face the truth, they deserve what they get by supporting inept spoiled authority.

https://robc137.substack.com/p/allergic-to-bullshit

George Carlin is one of my favorite philosophers. Others like Bill Hicks and Robert Anton Wilson also got it.

Without acknowledging the absurdity, we live in positive and negative delusions.

I’ve read just a bit of Cioran, and have one book. I have no need to comment extensively. Can’t say I agree or disagree, except in some instances. This, though, I CAN say. He is better understood when one reads his works when they are past, at least 75 years of age. I AM past that age by a few years.

I do think that had he looked at - he didn’t as far as I know, except for buddhism - the Eastern belief systems, rather than focusing on the Western, he may have been a bit more happy fellow. The Western offer lots of burdensome dogma, burdensome wrongness, control mechanisms, and little hope, and more that does not contribute to peacefulness of mind, psyche. That would be my recommendation for anyone. At least to brave a look for some time, not shutting it out completely from one’s experience.

Thanks for the essay. Nicely covered!